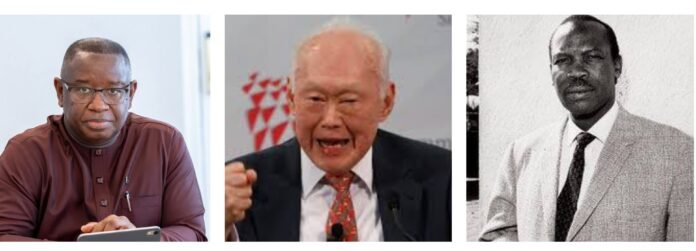

L-R: Sierra Leone’s President Julius Maada Bio, Lee Kuan Yew, Sir Seretse Khama

By Mahmud Tim Kargbo

When a people unshackle themselves from foreign rule there is a public theatre of hope. Flags are hoisted, anthems are learned, and leaders step forward with lofty declarations of unity, progress and dignity. Sierra Leone in 1961 lived that theatre, and Sir Milton Margai’s words still echo as a national creed.

But theatre alone cannot forge hospitals, courts or accountable treasuries. In many nations that became independent in the 1960s and later, deliberate statecraft, institutional steadiness and pragmatic leadership converted hope into sustained material improvement. In contrast, Sierra Leone and a number of West African neighbours have too often seen slogans eclipsed by clientelism, weak institutions and external interference that hinder popular advancement.

This essay compares Sierra Leone’s post-colonial trajectory with selected peers that gained independence in the same era or afterwards and achieved markedly better outcomes. The aim is not to deny the complexity of history or the continuing effects of imperialism. It is to show, with examples and sources, how choices about leadership and institution building make measurable differences in citizens’ standards of living.

Section 1 Sierra Leone in brief:

Sierra Leone won independence in 1961 amid high expectations for unity, development and social justice. Successive governments invoked powerful slogans but, in the view of many analysts, underinvested in accountability, public administration and rule of law. Weak institutions left the state vulnerable to corruption, patrimonial politics and periodic breakdowns of order. For a fuller account of the post-war Truth and Reconciliation Commission findings see http://www.sierraleonetrc.org

Section 2 Comparative cases that underscore leadership and institutional effects:

Botswana 1966 A lesson in prudent leadership and resource governance

Botswana became independent in 1966 with extremely limited infrastructure and scant revenue. Effective early leadership under Sir Seretse Khama prioritised institutional continuity, rule-bound fiscal policy and a careful contractual approach to its diamond resources. The Botswana Government established the Ministry of Finance and conservative fiscal rules; it pursued partnership arrangements with diamond firms while retaining state oversight that channelled resources into education, roads and public health. The result was decades of relatively high growth, low corruption by regional standards and strong public investment. For development and governance data see http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/botswana and http://www.transparency.org

Mauritius 1968 Economic diversification and consensual politics:

Mauritius gained independence in 1968. Successive governments embraced pragmatic economic policy, export diversification, social investment and a consensual model of governance that encouraged multi-party cooperation and technocratic management. The island moved from a mono-crop economy to textiles, tourism and financial services while building robust social services. Mauritius regularly ranks high on the UN Human Development Index among African states. See http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/mauritius and http://www.hdr.undp.org

Singapore 1965 Rapid institution building under determined leadership:

Singapore became a sovereign state in 1965 and under Lee Kuan Yew built disciplined institutions, a corruption-intolerant civil service and an investment-friendly legal framework. The state balanced market openness with strong public planning, universal basic infrastructure and meritocratic administration. Singapore’s transformation shows how a small state can combine strong leadership with institutional incentives that reward competence. For background and economic records see http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/singapore and http://www.imf.org

Tanzania 1961/1964 Mixed record but notable public investment under Nyerere:

Tanzania (Tanganyika 1961 and Zanzibar 1963 later united in 1964) under Julius Nyerere pursued a social contract through policies such as ujamaa. While many of those policies later disappointed on efficiency grounds, the Nyerere period did institutionalise national education expansion and public service delivery in ways that helped raise basic literacy and health indicators in rural areas. The lesson is nuanced: visionary policies without responsive institutions can falter, but early public investments can produce long-term human capital gains. See http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/tanzania

Section 3 What these cases share in common:

Early prioritisation of institutions over personality

Leaders who insulated civil service appointments from partisan capture and who enshrined rules for fiscal management created predictable environments for investment and service delivery. Botswana and Singapore show that continuity and meritocratic public administration matter.

Transparent and pragmatic resource management

Where resource wealth was present, states that created transparent frameworks and ring-fenced revenues for public investment avoided the classic resource curse. Botswana’s approach to diamond revenues contrasts strongly with regimes that allowed resource rents to become patrimonial payoffs. See http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries

A limited but crucial tolerance for dissent and legal predictability

Countries that allowed institutions of accountability, courts, audit offices, free press,to operate with some independence generated better outcomes. Mauritius and Singapore each built predictable legal settings that supported commerce and social policy.

Investment in human capital and basic services

Sustained funding for education, basic health and rural infrastructure produced measurable improvements in living standards and productivity. Long term gains in literacy and life expectancy translate into economic resilience. See UNDP human development resources at http://www.hdr.undp.org

Section 4 Why Sierra Leone and much of West Africa lag behind:

Institutional fragility and personalised politics

Many West African states, including Sierra Leone, have seen political power concentrated in executive hands, weakening checks and balances. Patronage networks fuel resource diversion and discourage meritocracy in the civil service.

Incomplete resource governance

Where natural resources exist, weak contractual terms, opaque revenue management and limited reinvestment have reduced potential public benefit.

External dependency and asymmetric influence

Neocolonial economic ties, structural adjustment legacies and dependence on foreign aid and private capital can constrain policy space. Conditioning tied loans, prioritisation of external creditors, and skewed trade relations often privilege external actors’ interests over domestic development needs. For discussions on aid and conditionality see http://www.worldbank.org and http://www.imf.org

Security shocks and conflict legacies

Civil war, coups and chronic insecurity disrupt development. Sierra Leone’s 1991 to 2002 conflict and subsequent security strain consumed resources and weakened institutions, a pattern seen across conflict-affected states.

Section 5 Policy lessons and prescriptions:

Strengthen public financial management and transparency

Credible audit offices, open budgeting and legal enforcement of financial irregularity can restore public trust and channel resources toward services. See audit and governance resources at http://www.auditservice.gov.sl and http://www.transparency.org

Build a meritocratic, professional civil service

Recruitment based on competence and protection from partisan dismissal increase state capacity for policy delivery. Training and neutral promotion tracks are essential.

Institutionalise resource revenue sharing and sovereign saving

Contracts that protect the public interest, sovereign wealth mechanisms and transparent reporting reduce rent capture and fund long-term development priorities. See extractive industry guidance at http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries

Encourage a plural public sphere and judicial independence

Independent courts and media act as vital counterweights to illiberal concentration of power. International indexes and civil society coalitions can help monitor progress. See http://www.transparency.org and http://www.afrobarometer.org

The divergence between countries that emerged from colonial rule and subsequently improved living standards, and those that have lagged, is not fate. It is the product of choices about leadership, institutional design and the management of resources. Botswana, Mauritius, Singapore and, in specific respects, Tanzania, each show that prudent governance and institutional investment can convert limited resources into broad-based development. Sierra Leone and many West African nations continue to wrestle with the legacies of weak institutions, elite capture and external dependencies. Confronting those realities candidly, bolstering transparent public finance, and empowering a professional civil service are pragmatic first steps toward transforming political rhetoric into durable human progress.