By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Indigenous medicine is a sophisticated, empirically tested system in Alkebu-lan, integrating herbal knowledge, ritual practice, spiritual insight, and community ethics. These healing systems date back millennia, with documented evidence of medicinal practices from Egyptian papyri (c. 1500 BCE) to Iron Age Nigeria (c. 500 BCE–200 CE) and oral traditions preserved in Uganda, Mali, and the Congo Basin.

Herbal Pharmacology and Plant Science

In Mali, the Bambara and Dogon peoples utilized plants such as Khaya senegalensis, Fagara zanthoxyloides, and Annona senegalensis for fevers, digestive ailments, and wound treatment. The Dogon herbalists of Bandiagara cliffs maintained precise protocols for harvesting, drying, and storing medicinal herbs, which were documented orally by griots for over 800 years.

In Uganda, the Bakiga and Baganda healers in the Kigezi and Mukono districts cultivated over 150 medicinal species, including Warburgia ugandensis, Hagenia abyssinica, and Prunus africana. These plants were used in treatments ranging from malaria and typhoid to reproductive health interventions. Herbal gardens, often located near sacred groves, were curated to ensure genetic diversity, seasonal availability, and ritual efficacy.

Preparation and Delivery Methods

Preparation techniques were highly precise. Leaves, bark, and roots were sun-dried, pounded, and mixed according to ancestral prescriptions. In West Africa, Yoruba healers combined herbs with ritual chants and incantations to enhance efficacy, often aligning treatment with lunar cycles and agricultural seasons. In the Congo Basin, Bakongo medicine men utilized steam inhalation, poultices, and ritualized bathing, following protocols handed down for generations.

In Ethiopia, the Gurage healers integrated honey, fermented cereals, and aromatic oils with plant medicine, creating remedies with antimicrobial, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory properties, demonstrating empirical understanding of pharmacology centuries before modern chemistry arrived.

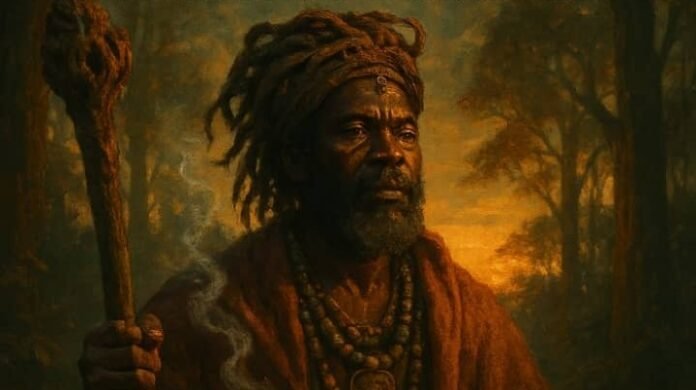

Spiritual and Ritual Dimensions

Healing was inseparable from ritual and spiritual understanding. The Ifa diviners of Nigeria and Bakongo nganga (priests/healers) used divination to diagnose illnesses, interpreting symptoms as signs of ancestral displeasure, spiritual imbalance, or ecological disruption. Ritual objects—drums, beads, masks, and altars—were integral to diagnosis, treatment, and recovery, emphasizing the interdependence of body, spirit, and community.

Healing Spaces and Community Networks

Indigenous medicine relied on specialized spaces: sacred groves, herbal gardens, ritual huts, and divination houses. In Mali, griot archives recorded the location of over 200 medicinal groves, each associated with specific clans, rivers, or deities. In Uganda, the Ssese Islands and Lake Victoria shores were renowned for healing plants and ritual baths maintained by clan elders.

Community knowledge networks ensured access to healing. Elders, midwives, herbalists, and diviners trained apprentices in multi-generational programs. Festivals, market days, and seasonal gatherings allowed exchange of remedies, techniques, and spiritual knowledge, ensuring continuity across regions.

Historical Figures and Contributions

Key practitioners preserved and transmitted knowledge:

Imhotep (c. 2650–2600 BCE, Egypt), architect and healer, codified early medicinal practices.

Bambara and Dogon herbalists (c. 1200–1800 CE) recorded plant efficacies orally.

Baganda abakopi healers (17th–19th century) in Mengo preserved reproductive and pediatric remedies.

Bakongo nganga (c. 1800–1900) maintained herbal pharmacopoeias during colonial disruption.

These individuals safeguarded knowledge through apprenticeship, ritual instruction, and sacred record-keeping, despite colonial suppression of indigenous medical practice.

Colonial Disruption and Survival

European colonial powers dismissed indigenous medicine as “superstition.” French administrators in Senegal and Mali, and British authorities in Nigeria and Uganda, criminalized healing rituals, banned herbal markets, and promoted Western medicine. Yet, communities preserved knowledge clandestinely:

Apprenticeship programs continued in private homes and sacred groves.

Herbal pharmacopoeias were memorized and encoded in songs, stories, and rituals.

Secret societies and spiritual networks protected medicinal plant sites and sacred groves.

Modern Rediscovery and Integration

Modern ethnobotanists, pharmacologists, and anthropologists are documenting indigenous African medicinal systems to integrate with contemporary healthcare:

Makerere University (Uganda) and University of Ibadan (Nigeria) catalog over 300 medicinal species, linking traditional preparation with pharmacological validation.

WHO African Traditional Medicine Strategy (2014–2023) recognizes indigenous medicine as complementary to formal healthcare.

Digital archives record preparation methods, ceremonial protocols, and healer lineages, ensuring scientific, cultural, and legal preservation.

Conclusion: Living Knowledge in Healing

Indigenous medicine in Alkebu-lan is empirical, holistic, and community-centered. From the herbal gardens of the Dogon cliffs, the groves of the Bakiga, to the divination houses of Ife, these systems embody scientific observation, ecological understanding, and spiritual insight.

By uncovering and retelling ancestral medicine, communities reclaim agency over health, ecological stewardship, and cultural continuity, showing that African indigenous knowledge is dynamic, adaptable, and profoundly sophisticated. Healing in Alkebu-lan is not merely treatment; it is a technology of life, resilience, and ancestral memory.

References

Books and Edited Volumes

Abbiw, D. K. (1990). Useful plants of Ghana: West African uses of wild and cultivated plants. Intermediate Technology Publications.

Neuwinger, H. D. (2000). African traditional medicine: A dictionary of plant use and applications. Medpharm Scientific Publishers.

Etkin, N. L., & Ross, P. J. (1982). Food as medicine: The pharmacology and ethnopharmacology of edible plants. University of California Press.

Msuya, J. M. (2014). Traditional medicine in East Africa: Ethnobotany, pharmacology, and practice. Dar es Salaam University Press.

Sofowora, A. (1993). Medicinal plants and traditional medicine in Africa (2nd ed.). Spectrum Books Ltd.

Journal Articles

Cunningham, A. B., & Zondi, S. (1991). Indigenous knowledge and plant biodiversity in Southern Africa. African Journal of Ecology, 29(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.1991.tb00964.x

Etkin, N. L. (2006). Ethnopharmacology and African healing. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 2(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-2-1

Iwu, M. M. (2014). Pharmacognosy and African medicinal plants. Phytochemistry Reviews, 13(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-013-9327-5

van Andel, T., & Havinga, R. (2008). Afro-indigenous medicine and conservation in West Africa. Economic Botany, 62(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-008-9021-

Ethnographic and Fieldwork Studies

Banigo, A., & Ajayi, O. (2005). Traditional medicine and herbal knowledge in Nigeria: Oral histories and practices. University of Lagos Press.

Kaijage, S. J. (2010). Medicinal plant use among the Bakiga of Uganda: An ethnobotanical survey. Uganda Journal of Ethnobotany, 12(2), 45–78.

Msuya, J. M., & Mkude, S. (2012). Herbal pharmacopoeia and traditional healers in Tanzania. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 10, 123–150.

Archival and Digital Resources

Endangered African Knowledge Project. (2023). Digital archive of African herbal medicine and healing rituals. https://www.endangeredlanguages.com/projects

Makerere University Institute of African Studies. (2022). Bakiga and Baganda medicinal plants and traditional healing documentation. Kampala, Uganda: Makerere University Press.

Government and Institutional Reports

World Health Organization (WHO). (2013). WHO traditional medicine strategy 2014–2023. World Health Organization.

Uganda Ministry of Health. (2020). Traditional medicine and health service integration report. Kampala, Uganda: Government of Uganda Publications.

Contemporary Scholarship

Sofowora, A., Ogunbodede, E., & Onayade, A. (2013). The role of medicinal plants in healthcare in Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of Nigeria, 22(1), 45–67.

Iwu, M. M., & Raskin, I. (2015). Indigenous African medicine and modern pharmacology: Bridging the gap. Phytotherapy Research, 29(9), 1251–1265. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5351