By: Israel Y.K. Lubogo – King’s College Budo

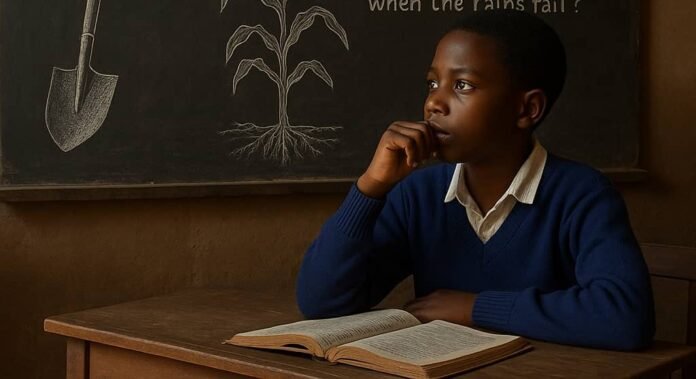

When I was still at Budo Junior, one of my teachers asked us to draw a hoe. We all drew it perfectly. Then he asked us to name the parts of a maize plant—we listed them with pride. Finally, he asked: “But can you use what you know to feed Uganda when the rains fail?”

The class went silent. I still remember that silence. It was heavy. It was embarrassing. And it has never left me.

Now I sit at King’s College Budo, older, wiser, and more restless. That question still follows me: What good is knowledge if it cannot feed us, heal us, or lift us?

That silence, I now realize, was not just ours as children. It was the silence of a curriculum built to repeat, not to create; to copy, not to solve. It was the silence of a nation clever in the past but unprepared for the future.

And yet, before us burns a new fire. Some call it Artificial Intelligence. I call it the new hoe, the new pen, the new spear. To reject it is to remain in silence forever. To embrace it is to finally answer my teacher’s question: Yes, we can feed Uganda. Yes, we can build. Yes, we can lead.

I. The Poverty of Yesterday’s Curriculum

Our education still trains us like clerks of empire. We cram. We copy. We memorize. We pass exams but we fail communities. We recite the rivers of Asia but cannot manage the floods in Kasese. We draw maize roots neatly but famine still grips Karamoja.

This is not the weakness of Ugandan children. It is the weakness of a curriculum designed to produce servants, not sovereigns.

Meanwhile, elsewhere the story is different. In Beijing, even primary schoolers now have AI as a mandatory subject. In Hong Kong, through the AI4Future project, students co-design their AI curriculum alongside teachers, learning not just coding but ethics. In the US, schools like Alpha use AI tutors that personalise lessons in real time. And in Estonia, an entire generation is being equipped with AI accounts, tools, and teacher training under their AI Leap initiative.

And we? We are still bound by chalk.

II. The New Literacy

When my father was young, illiteracy meant you could not read or write. For my generation, illiteracy means you cannot speak the language of new tools.

This is not about machines replacing us. It is about machines multiplying us. A farmer with a hoe can feed a family. A farmer with data and sensors can feed a nation. A nurse with a stethoscope can treat one patient. A nurse with diagnostic tools can treat hundreds.

To deny us this literacy is to blindfold us while our peers look through telescopes. It is to send us to a marathon barefoot, while others fly.

Stanford University already teaches high schoolers not just how AI works, but how it shapes society and ethics. Should Uganda’s children remain silent while the rest of the world learns to speak fluently with the tools of tomorrow?

As Paulo Freire warned: “Education is either an instrument of liberation or an instrument of domination.” Without this literacy, our curriculum chains us. With it, it frees us.

III. Why Uganda Cannot Wait

Some still ask: “Why should a farmer’s child in Busoga learn this?”

Because the hoe alone is no longer enough. Tomorrow’s farmer must read the clouds, measure the soil, and sell to markets beyond the village. Already, students in Estonia are learning these skills as part of their basic education.

Others ask: “Why should a teacher in Arua or a nurse in Iganga care?”

Because classrooms will soon be guided by AI teaching assistants, and medicine sharpened by intelligent diagnostics. Without this knowledge, our own professionals will be left behind in their own homeland—while their peers in Asia, Europe, and America move ahead.

This is not foreign. This is not copy-and-paste. This is Uganda refusing to remain last in the queue of progress.

IV. Guarding the Soul of the Future

But let us be clear: fire can warm, but it can also burn. These tools are powerful but not pure. They carry human bias, greed, and temptation. That is why we must not only use them—we must question them.

This is why the world’s leading schools teach ethics alongside AI. Stanford’s high school AI course insists students must ask: Should this machine exist? Should this decision belong to an algorithm? Uganda must do the same.

For what use is a nation of coders without conscience? That is not education—it is danger.

V. A Vision of Our Classrooms

This is the Uganda I dream of:

A P.3 child in Jinja solving problems with new tools as naturally as reciting multiplication tables.

An O-level student in Masaka building a simple intelligent model the way we once built toy wire cars.

An A-level graduate in Gulu debating not only Hamlet but also whether a machine should ever decide the fate of a man.

In America, students already use adaptive tutors that give instant feedback. In China, children are required to learn AI from primary school. In Estonia, teachers are trained to guide AI literacy as carefully as mathematics. Why should Uganda’s child be denied what the world now calls basic survival?

This is not utopia. This is survival. This is dignity. This is sovereignty.

Conclusion: From Silence to Fire

I still remember that Budo Junior silence—the silence of children who could draw a hoe but not feed their nation. That silence is still with us, written into our exams, our lectures, our chalkboards.

But the fire of tomorrow will not wait. Uganda must choose: to remain in silence or to rise in fire.

If we refuse, the epitaph will read:

“Here lies a nation that passed exams but failed the test of destiny.”

But if we dare, our testimony will declare:

“Here rose Uganda, bold enough to teach her children not to copy but to create, not to kneel before machines but to master them, not to borrow intelligence but to author it.”