By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Uganda, with one of the youngest populations in the world, stands at a demographic crossroads. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and recent census data, more than 75% of Ugandans are under the age of 30 (Uganda Bureau of Statistics [UBOS], 2024). This “youth bulge” is often celebrated as a potential engine of innovation and productivity, a promise that Uganda could reap the so-called demographic dividend. Yet the lived reality is far more troubling: in many regions, especially Bukedi, Lango, Karamoja, and Busoga, the rate of young people classified as “Not in Employment, Education, or Training” (NEET) exceeds 60%, with Bukedi registering 62.6%, Lango 62.3%, and both Karamoja and Busoga 60.9% (Monitor, 2024). Nationally, about 42.6% of youth aged 15–24 fall into this NEET category, underscoring the structural depth of the crisis (Uganda Radio Network, 2024). These figures are not simply statistical curiosities; they are markers of a generational rupture, a sign that millions of young Ugandans are being left on the margins of economic life.

The distinction between “unemployment” and “NEET” is crucial here. Traditional unemployment rates in Uganda appear deceptively low — often reported at around 4–5% among youth — because the measurement only counts those actively looking for work (The Global Economy, 2023). In an economy dominated by subsistence agriculture, casual labor, and informal trading, many youth survive in underemployment or opt out entirely from seeking jobs due to discouragement. The NEET measure, by contrast, captures those disengaged from work, study, or training altogether, thus providing a fuller picture of idleness. In Bukedi and Lango, where over six out of ten young people are NEET, this disengagement represents not only a personal struggle but also a systemic failure of institutions to absorb the country’s human capital into meaningful economic and social participation.

Regional disparities sharpen the story. The highest NEET rates cluster in Northern and Eastern Uganda, regions historically marked by war, displacement, and structural neglect. Karamoja, with 60.9% youth idleness, is scarred by cycles of conflict, cattle rustling, and limited infrastructure, leaving education and employment opportunities scarce (Monitor, 2024). Similarly, Busoga, despite its fertile soils and proximity to industrial centers like Jinja, records one of the highest NEET burdens. Such contradictions illustrate how development is unevenly distributed across Uganda’s regions, reinforcing a cycle where already disadvantaged areas see their youth trapped in prolonged inactivity. By contrast, more economically integrated regions like Kigezi (39.4%) and Ankole (39.8%) report significantly lower NEET rates, though these too remain alarmingly high by international standards (Monitor, 2024).

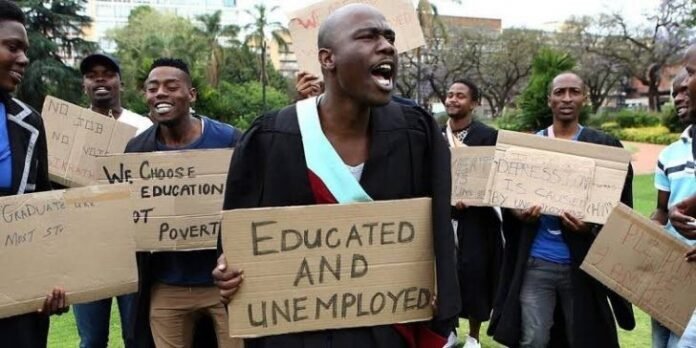

The implications are both economic and social. Uganda’s working-age population grows by an estimated 700,000 annually, yet the formal economy generates only about 90,000 jobs each year (International Labour Organization [ILO], 2023). This mismatch creates a deficit of over 600,000 new entrants to the labor market who must seek informal livelihoods or resign themselves to idleness. The result is a pressure cooker of frustration, evidenced in rising migration, the proliferation of precarious work, and the vulnerability of idle youth to crime, substance abuse, or even recruitment into violent groups. In a society where education is widely valorized as the pathway to advancement, the dissonance between years of schooling and the absence of dignified employment opportunities feeds a dangerous sense of betrayal among Uganda’s younger generations.

Scholars of development have long warned that a youth bulge, if not matched with opportunities, becomes less a dividend than a liability. Economists like Collier (2007) have argued that under conditions of exclusion, large youth cohorts can destabilize societies, eroding trust in governance and weakening social cohesion. Uganda is no exception. When NEET rates surpass 60% in whole regions, it signals that an entire cohort risks becoming a “lost generation,” caught between formal systems of education and labor markets that cannot absorb them. Moreover, the phenomenon of regional concentration — with Northern and Eastern sub-regions bearing the heaviest burdens — points to structural inequality that deepens national fault lines.

Addressing this crisis requires more than rhetorical appeals to entrepreneurship, a common refrain in policy discourse. While government programs such as the Youth Livelihood Programme (YLP) and the Parish Development Model (PDM) aim to provide capital and skills to young people, evaluations show mixed outcomes, often undermined by limited reach, mismanagement, or lack of complementary infrastructure (Kasirye, 2022). The UBOS data compels a more serious reckoning: without sustained investment in industrialization, vocational training, and equitable regional development, the gap between Uganda’s youthful aspirations and actual opportunities will continue to widen. As the proverb from the Baganda reminds us, “Obulamu bwa munno obwo bwo” — “Your neighbor’s life is also your own.” The fate of idle youth is not theirs alone to bear; it will ripple into the economy, politics, and the moral fabric of the entire nation.

International comparisons add another layer of urgency. Globally, the average youth NEET rate stands at around 21% according to the ILO (2023). Sub-Saharan Africa averages higher, with some countries nearing 30–35%. Uganda’s national figure of 42.6%, and regional peaks above 62%, place it among the worst globally. This contrast should not be dismissed as merely a product of differing statistical definitions. It instead highlights Uganda’s profound structural vulnerabilities: a high fertility rate (averaging 5.2 children per woman), limited industrial diversification, and underinvestment in education beyond the primary level (World Bank, 2024). As long as the economy remains anchored in low-productivity agriculture, the majority of youth will continue to find themselves excluded from meaningful, stable work.

The story of Uganda’s youth is therefore a paradox — a country rich in human potential yet unable to translate this demographic endowment into prosperity. Numbers alone tell a stark tale, but behind every percentage is a young life stalled, a dream deferred. To speak of 62.6% NEET in Bukedi is not to speak of abstract data; it is to invoke the faces of young men and women idling at trading centers, cycling between short-lived ventures, or resigned to waiting. It is to glimpse the silent erosion of hope in classrooms that feed into jobless futures. The gravity of these statistics lies precisely in their human weight.

References

Collier, P. (2007). The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. Oxford University Press.

International Labour Organization. (2023). Global employment trends for youth 2023. Geneva: ILO.

Kasirye, I. (2022). Assessing the effectiveness of youth livelihood interventions in Uganda. Economic Policy Research Centre (EPRC) Working Paper. Kampala.

Monitor. (2024, October 1). Youth unemployment: Northern and Eastern regions struggle most. Daily Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.monitor.co.ug

The Global Economy. (2023). Uganda: Youth unemployment rate. Retrieved from https://www.theglobaleconomy.com

Uganda Bureau of Statistics. (2024). National Population and Housing Census 2024: Provisional results. Kampala: UBOS.

Uganda Radio Network. (2024, September 15). Youth urged to innovate as govt revamps job strategy. Retrieved from https://ugandaradionetwork.net

World Bank. (2024). World Development Indicators: Uganda. Washington, DC: World Bank.