By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

“The song of the sacred and the drum of the polity can never be wholly separated; they beat in the same chest of the nation.” — African proverb

Introduction

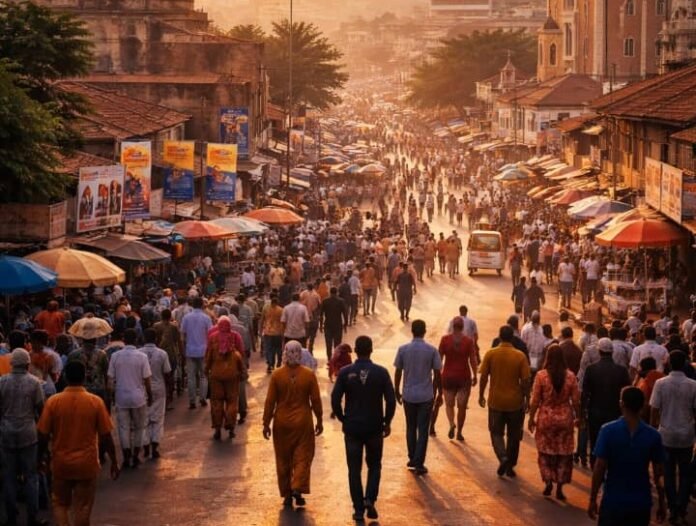

Let’s be honest: if you walk through almost any African city on a weekday morning, you can’t help but notice the mix of sounds that greet you. Church bells clang, mosques broadcast their calls to prayer, and campaign vans blast slogans that make you wonder whether you’re witnessing a civic rally or a festival of faith. And really, in many ways, it is both. Here, governance isn’t just about policy documents tucked away in government offices or debates in parliament; it’s about morality, community, and a kind of spiritual scoreboard that citizens seem to keep in their heads. People are constantly weighing whether leaders act ethically, whether their words align with religious teachings, and whether their policies reflect what’s considered “just” according to centuries-old moral traditions. Pew Research Center (2023) tells us that over 85% of Africans admit religion affects their political choices at least moderately, which is huge if you think about it. Faith isn’t just a backdrop; it’s the stage, the lighting, and the orchestra all at once. And like the Yoruba say, “He who prays for a long journey must respect the road ahead,” reminding us that spiritual guidance and civic responsibility are tangled up together in ways that can’t be neatly separated.

Now, don’t get me wrong—religion isn’t just a thing that wakes people up in the morning. It organizes neighborhoods, shapes moral behavior, and even acts as a kind of social GPS that helps people figure out what’s right and wrong. Faith-based organizations mediate disputes, provide social services, and educate communities, particularly when the state is too stretched or too slow to respond (Afrobarometer, 2024). Politicians know this, of course, and they engage religious networks to earn legitimacy, rally support, or sometimes just look like they’re on the “right side of morality.” Meanwhile, citizens expect leaders to not just govern, but to act in ways that feel morally sound. In Africa, governance is a constant negotiation between law, ethics, and spirituality, and ignoring one of these dimensions is like trying to drive a car with a missing wheel.

Historical Foundations of Religious-Political Power

If you think this mix of politics and faith is new, think again. Long before colonial borders were drawn, African societies had their own intricate dance between spiritual authority and political power. Take Buganda, for example: the Kabaka wasn’t just a king; he was semi-divine. Every decree he issued had both a political and spiritual weight, and the community measured his legitimacy in moral and ritual terms, not just administrative efficiency. Then there’s the Yoruba kingdoms, where Obas were expected to maintain cosmic order through religious ceremonies as much as through governance. Leadership wasn’t just about passing laws or collecting taxes—it was about balancing social, moral, and spiritual scales (MDPI, 2021). There’s a Malian proverb that goes, “When the roots of a tree are deep, it does not fear the storm,” and that really captures the idea that leadership grounded in spiritual legitimacy had resilience and authority that extended beyond mere politics.

Colonialism, as you might expect, shook things up. Europeans tried to standardize governance through secular institutions while simultaneously using Christianity as a tool of control. Meanwhile, Islam continued to spread through trade networks, offering alternative moral and political authority. So, by the time African nations gained independence, they inherited a hybrid system: secular law alongside faith-based legitimacy, modern institutions sitting on top of centuries-old spiritual traditions. This explains a lot about contemporary Africa: faith isn’t just a personal choice; it’s a structural part of governance. People evaluate leaders based on moral and spiritual alignment, not just policy success, which makes politics here fascinatingly messy, rich, and often unpredictable.

Religion as a Tool for Political Legitimacy

Let’s get real: if you want to understand African politics today, you have to understand how politicians use religion. Take Uganda: presidential speeches are loaded with Christian rhetoric, framing obedience to the state as a moral and spiritual duty (AP News, 2023). Politicians attend church services, sponsor religious projects, and make sure their public image screams moral responsibility. Nigeria’s a bit different but just as complex: the north is largely Muslim, the south largely Christian, and political campaigns are carefully crafted to appeal to faith-based constituencies. What’s fascinating is how religion becomes both a bridge and a barrier: it can rally people around a cause, but it can also exclude anyone who doesn’t fit the dominant moral narrative (Dw.com, 2024).

Religion’s influence isn’t just for show during election season. Leaders often invoke divine guidance to justify policy decisions, from education reform to healthcare initiatives to economic planning. But—and this is a big but—this power comes with risks. Manipulating faith to cement authority can suppress dissent, marginalize minority communities, and even justify questionable policies. That’s why African proverbs exist to warn leaders: “He who climbs a tree cannot blame the wind for his fall.” Basically, if you exploit spirituality for personal gain, you’re bound to face consequences, whether ethical, social, or political.

Case Studies: Religion and Politics in Practice

Nigeria is a prime example of how religion can shape everything from voting patterns to civil unrest. The Middle Belt, in particular, shows what happens when politics and faith get tangled: land disputes, ethnic rivalries, and resource conflicts are often interpreted through religious lenses. Extremist groups like Boko Haram exploit these divides, fusing political grievances with religious ideology to recruit followers and challenge the state. Yet, at the same time, religious institutions provide a counterbalance: mediating conflicts, fostering civic engagement, and advocating for social justice (Pew Research Center, 2023). It’s a delicate balance, like walking on a tightrope above a field of fireworks.

Uganda offers another interesting lens. Politicians publicly embrace Christianity but privately consult traditional spiritual authorities—a blend of the modern and the ancestral. Pentecostal churches wield enormous influence over morality, public discourse, and grassroots activism. They organize social programs, monitor government initiatives, and mobilize voters, demonstrating that religion isn’t just spiritual—it’s a political instrument too (AP News, 2023). Kenya, meanwhile, shows the power of faith-based civic engagement: organizations like the National Council of Churches facilitate voter registration, provide civic education, and monitor elections, helping citizens understand their rights while holding authorities accountable (Verbum et Ecclesia, 2022). In South Africa, almost everyone identifies with a religion despite formal secularism, meaning that faith continues to shape social policy, ethical norms, and political debates. These cases show that religion can simultaneously stabilize and destabilize societies, depending on how it is wielded.

Religion and Public Policy

Now, let’s talk about the nitty-gritty of governance. Religion shapes laws and norms around marriage, sexuality, education, public morality, and family life. Issues like reproductive health, LGBTQ+ rights, and alcohol regulation often see faith-based organizations lobbying for certain outcomes. At the same time, these organizations fill critical gaps in social services—schools, hospitals, and humanitarian aid—especially when the state is under-resourced. While these contributions are undeniably beneficial, they can also entrench conservative norms, reinforce gender hierarchies, and slow progressive reform. Afrobarometer (2024) reports that 62% of East Africans think political leaders should consult religious authorities before making major policy decisions, a figure that underscores both the enduring legitimacy of faith and the challenge of balancing pluralism with tradition.

Youth, Gender, and Minority Perspectives

Religion doesn’t impact everyone equally, and that’s important to remember. Women often face structural inequalities reinforced by faith-informed laws on reproductive rights, inheritance, and education. Youth, meanwhile, are caught between honoring traditional religious norms and pushing for social and political change. Minority religious groups—indigenous faith practitioners, smaller denominations—often struggle to have their voices heard when dominant faiths dominate the political conversation. Yet these communities are vital for pluralism and inclusion, offering alternative perspectives that challenge entrenched norms. As the Baganda proverb goes, “Even the tallest tree cannot hide the small plants beneath it,” a reminder that minorities matter, and societies thrive when everyone’s voice is considered.

Ethical and Democratic Challenges

Religion in politics is a double-edged sword. On one side, it can inspire moral leadership, foster civic engagement, and strengthen social cohesion. On the other, it can justify authoritarianism, marginalize minorities, and suppress dissent. The ethical tension is constant: when does guidance become coercion, and how do you respect pluralism in a faith-driven context? African wisdom tells us, “Wisdom is like a baobab; no one individual can embrace it alone,” which is to say that governing with religion requires collaboration, accountability, and careful navigation of competing interests. Citizens, journalists, and policymakers alike must weigh religious influence carefully, preserving democratic principles and social inclusion while respecting the moral weight that faith carries in society.

Conclusion

Religion in African politics is complex, layered, and unavoidable. It informs moral reasoning, shapes civic engagement, and even determines policy outcomes. At the same time, it is a tool for power, exclusion, and mobilization. Understanding its influence is critical for anyone trying to grasp governance, ethics, or social life in Africa. The challenge is to harness faith responsibly, ensuring that spiritual and civic authority work together rather than against each other. When balanced well, the drumbeat of governance and the song of the sacred can coexist in harmony, producing societies where morality, ethics, and civic life reinforce one another rather than clash.

Bibliography

Afrobarometer. (2024). Religion and Political Attitudes in Africa. https://www.afrobarometer.org

Pew Research Center. (2023). Religious Landscape of Africa. https://www.pewresearch.org

Dw.com. (2024). Religion in Africa: High Tolerance for Other Faiths. https://www.dw.com

The Times. (2023). Massacre of Nigerian Christians Draws International Attention. https://www.thetimes.com

AP News. (2023). Religion and Politics in Uganda: Syncretism and Governance. https://www.apnews.com

Verbum et Ecclesia. (2022). Faith and Democratic Engagement in Kenya. https://verbumetecclesia.org.za

MDPI. (2021). Religion, Morality, and Policy in Africa. https://www.mdpi.com