Introduction

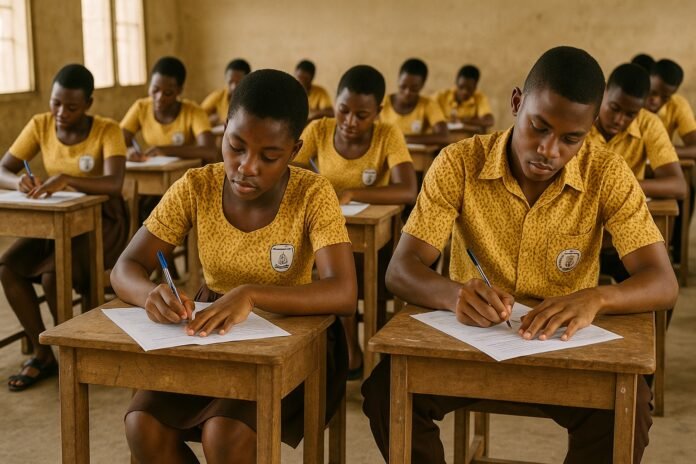

Religious schools are often seen as sanctuaries of discipline, morality, and integrity. Parents send their children to these institutions not only to acquire academic knowledge but also to be nurtured in values like honesty, humility, and faith. In Ghana, schools like the Adventist Day Senior High School and the Christian School have long prided themselves on producing not just intelligent graduates, but upright citizens grounded in Christian ethics. Yet recent developments have exposed a troubling contradiction: the very institutions that preach integrity are being implicated in examination malpractice.

The arrests made during the ongoing West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) reveal a crisis of values — one that challenges both the credibility of Ghana’s educational system and the moral authority of faith-based institutions.

The Scandal Unfolds

Authorities in Ghana, acting on intelligence from the West African Examinations Council (WAEC), recently arrested 14 individuals across different exam centers for alleged involvement in cheating. Those arrested included not only students but also teachers and invigilators — the very people entrusted with ensuring fairness.

Among the most shocking revelations was the shutdown of the Adventist Day Senior High School exam center in Kumasi. Mobile phones, which are strictly prohibited during WASSCE, were confiscated. Candidates were subsequently relocated to WAEC’s regional office to continue their exams under stricter supervision.

Equally disturbing was the case of the Christian School in Kukurantumi, where the proprietor and a teacher were arrested for creating a WhatsApp group to leak exam questions to students. What was intended to be a religiously guided environment of moral training instead became a hub for organized malpractice.

When Guardians Become Culprits

The betrayal in these cases cuts deeper because of the schools’ religious identities. In Christian teaching, values like truthfulness, accountability, and integrity are central. Adventist schools, in particular, emphasize discipline, honesty, and the belief that education is a sacred trust. Parents and society therefore hold such institutions to a higher standard.

Yet here we see religious schools implicated in practices that directly contradict their moral mission. Instead of serving as role models for ethics, they have become examples of corruption and short-term thinking. When teachers — the custodians of learning — collude in malpractice, the moral foundation of education crumbles.

The Wider Problem of Exam Malpractice

To be clear, examination malpractice is not confined to religious schools. WAEC reports that every year, cheating scandals plague various institutions, from public to private. Methods range from smuggling mobile phones into exam halls to organized networks leaking papers ahead of time.

The problem is systemic, fueled by:

Pressure to perform – Parents and schools often demand high pass rates, pushing students and teachers into desperation.

Weak supervision – In some centers, invigilators are compromised by bribes or personal relationships.

Cultural tolerance of shortcuts – In many societies, “beating the system” is admired, reinforcing dishonesty.

What makes the Adventist and Christian school scandals particularly damning is not that malpractice occurred, but that it occurred under the banner of faith.

Consequences Beyond the Classroom

The consequences of such scandals are far-reaching. First, they erode trust in Ghana’s education system. If students can cheat their way through high school, what does that say about the integrity of certificates issued? Employers, universities, and society at large may begin to doubt the competence of graduates.

Second, these incidents corrupt the moral fabric of students. When young people see adults — teachers, proprietors, invigilators — colluding in dishonesty, they internalize the message that ends justify the means. A student who cheats to pass exams today may cheat in business, politics, or relationships tomorrow.

Finally, religious institutions themselves lose credibility. When faith-based schools are caught in dishonesty, skeptics point to hypocrisy. The damage to reputation is not limited to the institutions but spills over to the faith communities they represent.

Counterpoints: The Systemic Pressure on Schools

While condemning malpractice is necessary, it is also important to understand the pressures driving it. Many religious schools operate in competitive environments where their survival depends on results. Parents often judge schools not by values but by pass rates. A poor record in WASSCE can lead to reduced enrollment, which threatens livelihoods.

Teachers, too, are under strain. With limited resources and overcrowded classrooms, some see malpractice as the only way to “help” their students succeed. None of this excuses dishonesty, but it highlights the urgent need for systemic reform.

The Way Forward

1. Stronger Accountability for Religious Schools

Religious organizations must hold their schools to higher standards. Leaders of the Adventist and Christian communities in Ghana should not brush these scandals aside but must investigate thoroughly and impose disciplinary action. Moral credibility depends on confronting wrongdoing transparently.

2. Strengthening WAEC Oversight

WAEC’s swift actions — arrests, fines, relocation of students — send a strong message. These must be sustained. Strict penalties for teachers and proprietors involved in malpractice are essential to deter future cases.

3. Redefining Success in Education

Parents and society must shift focus from grades to character. A student who scores an A through cheating is less valuable to society than one who earns a C with integrity. Schools should be judged on the holistic development of students, not just their WASSCE pass rates.

4. Role of Religious Leaders

Pastors, priests, and imams connected to faith-based schools must use the pulpit to reinforce the message that integrity is non-negotiable. Religious education must not be a formality but a living principle that governs practice.

Conclusion

The arrests at Adventist Day Senior High School and Christian School represent more than exam scandals; they symbolize a moral crisis in Ghana’s education system. When institutions that preach integrity are caught enabling dishonesty, society must pause and ask: what example are we setting for the next generation? What moral lessons are we teaching them?

Faith-based schools cannot claim the mantle of moral authority while cutting corners in the shadows. The choice before them is clear: either recommit to their spiritual mission of truth, or risk becoming indistinguishable from the very corruption they claim to oppose. In the end, integrity in education is not just about passing exams; it is about preparing a generation capable of building an honest, just, and thriving Ghana.