By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

In several public speeches, President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda asserted that, despite being land‑locked, Uganda is “entitled” to access the Indian Ocean. He warned that continued obstruction of such access could escalate tensions, potentially even leading to conflict. While the rhetoric is striking, it reflects deeper realities: Uganda’s structural trade disadvantages, regional ambitions, strategic constraints, and the imperatives of economic diversification. Rather than dismissing the claim as political posturing, it is essential to examine its economic, legal, infrastructural, diplomatic, and security dimensions.

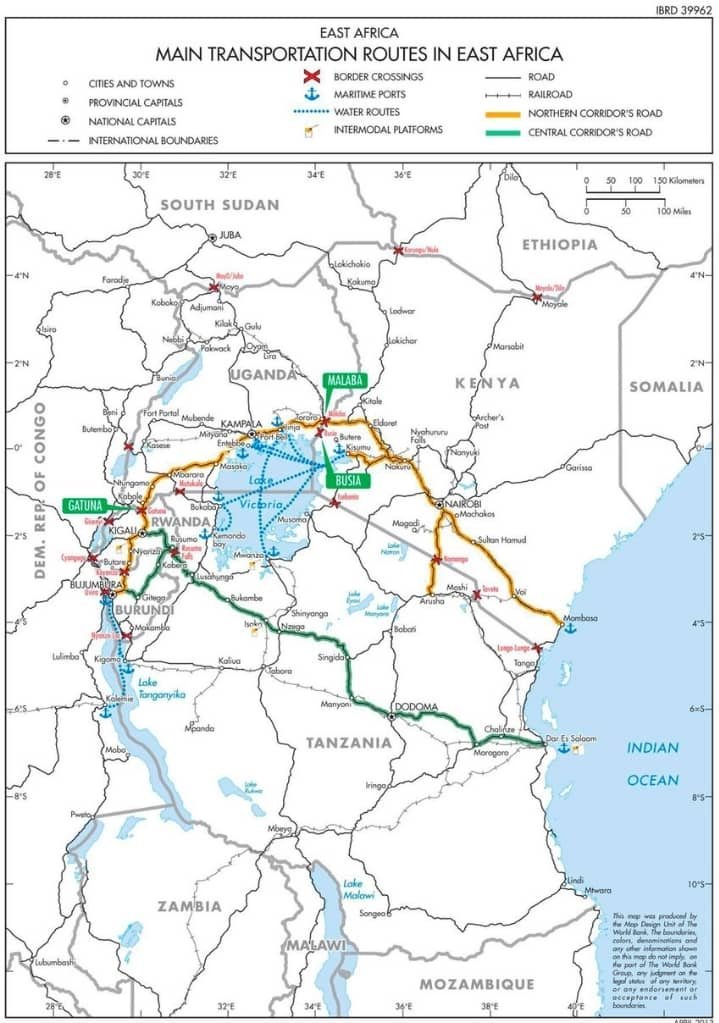

Uganda’s economic dependence on its neighbours for maritime access is profound. The country primarily relies on Kenya’s Port of Mombasa, through which the majority of Uganda’s imports and exports transit. In 2024, the Kenya Ports Authority recorded that Mombasa handled approximately 41.1 million tonnes of cargo, of which 13.4 million tonnes were transit goods—an increase of around 17.4% from 2023. Uganda alone accounted for 65.7% of this transit traffic, equivalent to roughly 8.81 million tonnes. This heavy reliance imposes both economic and strategic vulnerabilities: higher logistics costs, potential delays, and exposure to trade disruptions. In recognition of this structural fragility, Uganda has pursued alternative routes, notably the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) to Tanzania’s coast, reflecting an effort to diversify export corridors and reduce dependency on a single transit route.

From a legal perspective, Museveni’s claim intersects with international law. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), particularly Part X, Articles 124–128, land‑locked states possess the right of access to and from the sea through one or more transit states. These provisions, however, do not confer direct sovereignty over maritime zones. Museveni’s metaphor, likening Uganda to “the top floor of a block whose compound is claimed solely by the ground floor,” envisions equitable access akin to coastal states but exceeds conventional legal frameworks. Operationalizing such ambitions would require negotiated bilateral and multilateral treaties, harmonized tariffs, infrastructure agreements, and compliance with regional trade protocols. Uganda’s claim thus applies pressure on the East African Community (EAC) and transit states to reassess corridor arrangements in ways that respect both international law and national interests.

Strategically, Museveni’s emphasis on national defence and sovereignty—exemplified by his rhetorical question, “How do we build a navy when we have no sea?”—transforms a logistical discussion into a security one. In the contemporary geopolitical environment, control over maritime logistics, naval reach, and resilient trade corridors is critical for economic security. Uganda’s growing export base, including oil, minerals, and manufactured goods, accentuates the risk of overreliance on a single corridor. The rhetoric, therefore, functions not merely as political theatre but as a bargaining tool signaling Uganda’s intent to assert influence over its transit options while encouraging regional cooperation.

Diplomatically, Uganda’s reliance on Kenya grants both leverage and responsibility. Kenya commands port infrastructure, rail, and road corridors that form Uganda’s primary gateway to global markets, while Tanzania offers alternatives via its Central Corridor connecting Dar es Salaam and Tanga to Uganda. Recent bilateral agreements in 2025, including the removal of discriminatory excise duties and border congestion alleviation at Malaba and Busia, illustrate the ongoing negotiation of transit terms. Yet, Museveni’s warnings of potential conflict risk straining relations, and could be interpreted as confrontational rhetoric within the EAC framework rather than cooperative diplomacy.

Uganda’s maritime ambition is complemented by targeted infrastructure initiatives. In May 2025, the Islamic Development Bank approved $800 million in financing for rail links and trade-enabling projects connecting Uganda to Kenya. Additionally, in 2024, Uganda signed a contract with Turkish firm Yapi Merkezi to construct a 272‑km electrified rail section from Kampala to Malaba, linking to the Mombasa corridor. Kenya is simultaneously pursuing UAE funding to extend rail networks to the Ugandan border. While these developments make Uganda’s access aspiration feasible, practical challenges persist: port congestion, incomplete rail links, tariffs and non‑tariff barriers, infrastructure debt, and the necessity of coordinated sovereign cooperation.

The risks inherent in Uganda’s claims are multifaceted. Diplomatic escalation could arise if rhetoric is misinterpreted, while dependency on a single corridor exposes Uganda to cost shocks and supply chain fragility. Infrastructure projects carry financial and operational risks if demand is overestimated or management lapses occur. Strategic responses include bilateral negotiation with Kenya for cost-sharing and dedicated transit infrastructure, diversification through Tanzania’s Central Corridor, and operationalization of regional frameworks via the EAC and African Union to formalize rights for land‑locked states and harmonize transit.

In conclusion, Museveni’s insistence that Uganda should gain access to the Indian Ocean, accompanied by warnings of potential conflict, encapsulates both symbolic and practical considerations. Symbolically, it asserts national sovereignty and equitable access rights. Practically, it reflects economic vulnerability, infrastructural planning, strategic calculation, and regional diplomacy. The challenge for Uganda—and the EAC—is translating rhetoric into actionable treaties, efficient corridors, tariff harmonization, and collaborative frameworks. Done correctly, Uganda’s ocean ambition could enhance regional integration, trade competitiveness, and strategic autonomy; mishandled, it could provoke diplomatic tension or economic strain. While Uganda may not physically own the waters, its economic and strategic stakes in East Africa’s maritime corridors remain indisputably central to its future prosperity.

References

Kaija, E. M. (2025). Uganda’s Maritime Ambition: A Comprehensive Investigation of Museveni’s Ocean Claim. Unpublished manuscript.

Daily Monitor. (2025, November 10). Yoweri Museveni warns of future wars over access to the sea. Retrieved from https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/museveni-warns-of-future-wars-over-access-to-sea-5260392

The Star (Kenya). (2025, November 12). Museveni warns of future wars in EAC over Uganda’s access to the Indian Ocean. Retrieved from https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2025-11-12-museveni-threatens-war-with-kenya-over-indian-ocean

United Nations. (1982). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS): Part X – Right of Access of Land‑Locked States to and from the Sea, Articles 124–128. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/part10.htm

South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA). (2020, August). The Law of the Sea and Land‑locked States. Policy Briefing. Retrieved from https://saiia.org.za/research/the-law-of-the-sea-and-landlocked-states/

Kenya Ports Authority. (2024). Annual Port Traffic Statistics 2024. Mombasa: KPA.

East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP). (2025). Project updates and transit plans.

African Development Bank (AfDB). (2025). Kenya–Uganda Expressway Feasibility Study. Abidjan: AfDB.

Uganda Ministry of Works and Transport. (2024). Rail and Transport Infrastructure Development: Status Report 2024. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

Tanzania Ports Authority. (2025). Central Corridor Transit Traffic Annual Report. Dar es Salaam: TPA.