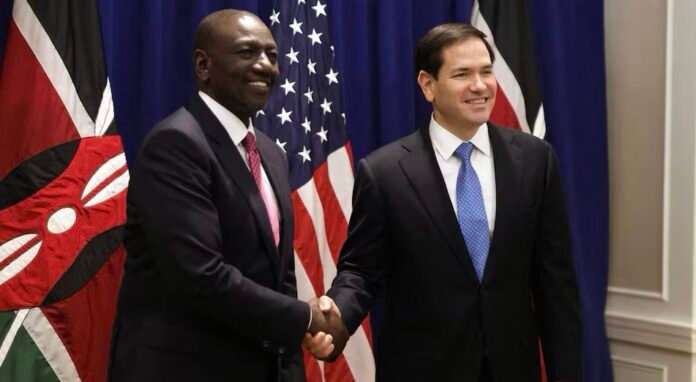

The United States has signed a landmark five-year health agreement with Kenya worth more than US$1.6 billion, marking the first of its kind under the administration’s revamped foreign-aid framework. The deal — inked on Thursday by U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Kenyan President William Ruto — signals a dramatic shift in U.S. global health policy toward direct state-to-state cooperation and away from traditional aid models.

Under what the U.S. now calls the America First Global Health Strategy, Kenya has committed to increasing its own health spending by roughly US$850 million over the next five years. In addition, the agreement emphasizes that health-care funding will go directly to the Government of Kenya — rather than flowing through non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as in the past.

Officials expect comparable agreements to be signed with other African countries in the near future. For Kenya, this represents a historic shift: the East African nation becomes the first African country to enter a full government-to-government health funding compact with Washington under the new strategy.

Why the U.S. says it’s shifting course

The new compact comes on the heels of the U.S. government’s dismantling of the longtime foreign aid agency, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), earlier this year. Many existing health-care programs in Africa — including HIV/AIDS treatment, malaria prevention, maternal and child health, and general disease control — had been run through USAID and an array of partner NGOs for decades. The closure of USAID left a significant vacuum in health financing across the developing world.

At the signing, Rubio criticized what he described as the “NGO industrial complex,” saying the previous model had encouraged inefficiency, fragmentation, and waste. Under the new compact, the U.S. government argues, resources will instead flow directly to Kenyan institutions such as the Ministry of Health, the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA), and other national health agencies — improving transparency, coordination, and long-term sustainability.

The framework also explicitly includes faith-based health providers alongside public and private clinics when it comes to funding eligibility — a move meant to broaden treatment access across different types of health-care delivery systems.

What this means for Kenya’s health system

For Kenya, the pact could translate into expanded capacity for infectious disease prevention and treatment — including HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and possibly polio. The shift to direct government funding and co-financing aims to strengthen the country’s health infrastructure with a long-term view towards self-reliance.

According to Kenyan health-sector officials, the deal will support multiple national institutions: from the Ministry of Health to the Directorate of Health Accounts, the National Public Health Institute, and supply-chain bodies like KEMSA. The agreement is expected to cover not only medicines and frontline health-care workers but also upgrades to management, procurement, data systems, and supply-chain infrastructure.

The funding will also facilitate Kenya’s wider ambition to expand Universal Health Coverage (UHC) under its broader domestic development plan. Government representatives have committed to transparency — insisting that “every shilling and every dollar will be spent efficiently, effectively, and accountably.”

Mixed reactions and what critics warn about

While some welcome the new model as a step toward sustainable, country-led health systems, the overhaul has drawn criticism from donors, health experts, and program beneficiaries. The abrupt elimination of USAID and the switch away from NGO-based support have raised serious concerns about gaps in ongoing programs. Many fear interruptions to HIV/AIDS treatment, maternal and child health services, and disease prevention initiatives long supported by external aid.

Critics argue that even as Kenya steps up domestic spending, there may be transitional delays: building supply-chains, ensuring staff are retained, and absorbing previously donor-funded health workers into government payrolls — all while maintaining service levels — is a complex process. Some also worry that the emphasis on efficiency and “ownership” might come at the cost of scale or coverage, especially in rural or underserved areas.

The shift also reflects a broader geopolitical recalibration: under “America First,” U.S. foreign aid is increasingly tied to bilateral agreements aligned with strategic priorities — potentially leaving out countries that do not meet certain political or governance criteria. Observers note that some high-need countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, may be left out of future deals if they are not considered strategic partners under the new paradigm.

What comes next

For now, all eyes will be on Kenya as the pilot case for the new aid model. U.S. and Kenyan officials have said they hope to sign similar compacts with other African nations by the end of 2025. If successful, the shift could mark a turning point in how global health aid is delivered across much of the developing world.

For Kenya, success will depend on how effectively the government can absorb new responsibilities — from financing to procurement, data management, workforce integration, and supply delivery — while maintaining or expanding access to essential health services.

For global health stakeholders, the new pact raises profound questions: can government-to-government deals match the agility and community-level reach of NGO-driven programs? Can they deliver better long-term sustainability — or will vulnerable populations risk falling through the cracks during the transition?

As the first $1.6 billion deal under the “America First” strategy takes effect, these uncertainties will soon become real-world tests — not only for Kenya, but for any country that hopes to succeed under the new U.S. approach to foreign health aid.

Source:Africa Publicity