By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Emkaijawrites@gmail.com

“The prophet who eats from the king’s table cannot see the blood on his hands.” – African Proverb

I. Introduction

Contextualizing the Issue

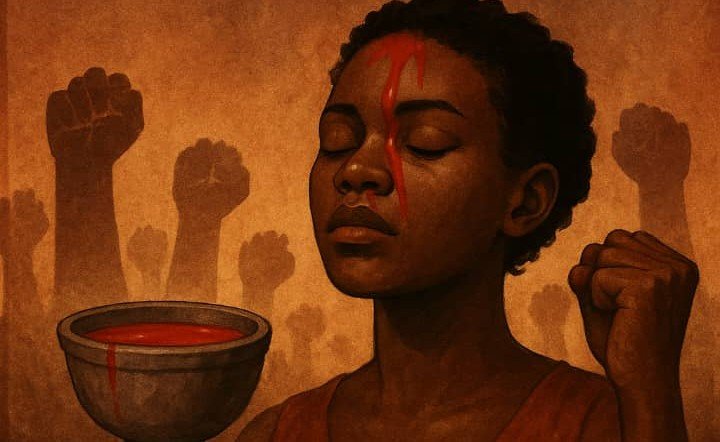

In the flickering shadows of dawn, where Africa’s ancestral fires once told stories of birth, courage, and covenant, a darker narrative now stirs—a return of the blood altars. Children vanish without trace, their absence silenced by superstition. Albinos are butchered for charms, their bones traded like cursed gold. The disabled, the orphaned, the vulnerable—all become sacred prey in a deadly economy of death masked as spiritual power. Human sacrifice, once considered an extinguished relic of Africa’s precolonial past, now thrives in new forms, whispered beneath the robes of prosperity prophets and behind the locked doors of political chambers.

Across the continent, media and human rights groups have chronicled chilling stories. In Uganda, where the BBC first broke the story in 2010, over 400 cases of suspected child sacrifice have been reported in the past decade—yet fewer than 20 perpetrators have ever faced justice. In Tanzania, the United Nations estimates that over 200 albino individuals have been murdered in the last 15 years, their limbs harvested for witch-doctors’ potions. A 2023 Interpol report confirmed the arrest of over 1,200 traffickers linked to ritualistic killings in West and Central Africa, with children as young as four sold for over $10,000 per body part in underground markets. These are not the stories of ancient Africa. These are the wounds of now.

Modern ritual sacrifice is no longer confined to forest altars—it is woven into elections, business contracts, spiritual warfare, and elite covenants. What was once the terrain of traditional priests now includes pastors, politicians, and security agents, all feeding a market of blood in exchange for power, protection, or wealth. The disturbing collusion between political structures and spiritual economies has transformed this issue from isolated horror to systemic crisis. Yet, theology has been mostly silent. And where the Church has spoken, it has often lacked courage, context, or clarity.

Purpose and Scope

This research paper rises as a lament, a sword, and a sanctuary. It seeks to develop a public theology that is both deeply biblical and rigorously multidisciplinary. By weaving scripture, anthropology, law, economics, psychology, African spirituality, and lived testimonies, this study confronts the multifaceted evil of human sacrifice in contemporary Africa. It does not ask merely what the Church believes—but what the Church must do.

Why does a continent that houses the fastest-growing Christian population also harbor the quietest pulpits on such grave matters?

Why do spiritual leaders remain mute while children’s blood cries from the ground?

Why does the state, meant to protect life, offer only investigations that lead to dust?

This paper positions the crisis of human sacrifice not just as a cultural pathology but as a spiritual emergency—requiring liturgical reform, prophetic resistance, and structural intervention. It is a call for a theology that bleeds, that listens to the graves, and that refuses to be domesticated by power.

Research Questions

To guide this sacred inquiry, the following questions shall be pursued:

1.What does the Bible teach about human sacrifice, and how can these texts be interpreted prophetically today?

2.How have African societies—both historically and in the present—navigated the reality of human sacrifice?

3.Which political, economic, spiritual, and psychological factors sustain the resurgence of this practice?

4.How can public theology confront these realities through advocacy, ethics, and transformative witness?

Methodology

The approach employed in this study is multidisciplinary biblical public theology—a tapestry of voices drawn from the Scriptures and the sciences, the academy and the altar. Through:

1.Biblical exegesis, key passages such as Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 22), the Molech prohibitions (Leviticus 18:21, Jeremiah 7:31), and Christ’s final sacrifice will be explored.

2.Historical and anthropological analysis, examining the cultural contexts of traditional sacrifice, colonial disruption, and postcolonial perversions.

3.Political economy, to trace how blood becomes currency in African power structures.

4.Human rights law, analyzing how national and international frameworks have responded or failed.

5.Psychological theory, to address trauma and the erosion of identity among survivors.

6.African Indigenous knowledge systems, to retrieve the life-affirming wisdom long overshadowed by false spiritualities.

7.Testimonial evidence, incorporating stories, interviews, and survivor narratives.

II. Biblical Foundations

A Theology That Refuses Blood on the Altar of Injustice

Exegetical Analysis of Key Texts

The Bible is not silent about blood; it is soaked in it. Yet not all blood is holy. Scripture draws a fierce distinction between sacrificial blood given in covenantal surrender, and the unjust bloodshed of the innocent—a theme that weaves from Genesis to Revelation like a crimson thread of warning. In Genesis 22, we meet Abraham, blade in hand, ascending Moriah to offer his son Isaac. For many, this is a text of obedience; but for Africa, it must also become a text of divine interruption. God halts Abraham, not to test only his faith, but to forever signal that human sacrifice is not the path to divine favour. A ram is provided, and the altar is transfigured from a site of death to one of substitutional grace. “God will provide the lamb,” Abraham says prophetically, laying the foundation for a theology that moves away from child blood toward redemptive life.

In Leviticus 18:21, the prohibition is explicit: “You shall not give any of your children to offer them to Molech.” This deity, worshipped through infant fire sacrifice, was condemned as an abomination that “profanes the name of the Lord.” Jeremiah 7:31 deepens this judgment, declaring that the Israelites’ imitation of Canaanite rituals—burning their sons and daughters in the Valley of Hinnom—was never commanded, never even entered God’s mind. The Hebrew here—“lo alah al libi”—is a divine heartbreak: “It never entered My heart.” That verse alone indicts every altar built on African soil where child blood has been poured out for political charm or business breakthrough.

In Amos 5:21-24, God declares His disgust for empty religion built upon injustice: “I hate, I despise your feasts… But let justice roll down like waters.” This rebuke echoes into our generation. It is not enough to build cathedrals while ignoring the cries of trafficked children. Sacrifice, if not soaked in justice, is blasphemy.

Theological Themes

The Bible’s confrontation with human sacrifice is not merely legal—it is deeply theological. At its core is the concept of the Imago Dei—that each human bears God’s image and is therefore sacred (Genesis 1:27). This doctrine shatters the logic of ritual murder. A human being is not an object for spiritual transaction; he or she is a walking icon of God.

The second core theme is covenant justice. Throughout the Prophets, God aligns Himself with the oppressed: the orphan, the widow, the stranger. In Exodus 22:22-24, God warns: “Do not take advantage of the widow or the fatherless. If you do and they cry out to me, I will hear their cry…” This divine siding with the vulnerable condemns any society where the voiceless are sacrificed for the ambitions of the powerful.

Then comes the theology of lament. From the blood of Abel crying from the ground (Genesis 4:10) to the martyrs beneath the heavenly altar in Revelation 6:10 crying “How long, O Lord?”, the Bible never lets the blood of the innocent evaporate. It remembers. It mourns. It demands justice. In this way, lament becomes holy resistance—a refusal to accept silence as peace.

Finally, in the person of Jesus Christ, we find the end of all blood sacrifice. His crucifixion, though steeped in political violence, becomes a subversion of ritual killing. Jesus is not just the Lamb; He is the Victim who exposes every altar of injustice. The Gospel does not sanctify sacrifice—it abolishes it, replacing it with resurrection.

Historical-Cultural Context of the Texts

To fully grasp the weight of biblical resistance to human sacrifice, we must step into the world of ancient Israel—a small, struggling people surrounded by empire and religious pluralism. In Canaanite religion, sacrifice—especially of the firstborn—was common during times of drought, war, or royal succession. The Molech cult, often practiced near fire-pits in the Valley of Hinnom (Gehenna), represented the state-sanctioned intersection of power and fear. Child sacrifice was thus not just spiritual—it was political. Kings and priests used it to secure rain, victory, and dynastic legitimacy.

God’s law, then, is revolutionary. It does not merely moralize; it reverses the logic of surrounding cultures. By outlawing human sacrifice, the Torah reclaims the child from the flames, the mother from mourning, the father from complicity. Israel was called to be different—to practice a holiness rooted not in bloodletting but in covenant faithfulness, economic justice, and care for the weakest.

In today’s Africa, the biblical texts demand the same revolution. When politicians bury fetuses beneath campaign stages; when pastors mix scriptures with spells; when children’s bodies are found in sugarcane fields with tongues cut out—we must reread Leviticus and weep. We must invoke Jeremiah and shout. We must remember that the valley of Hinnom is not just in Jerusalem—it is in Kampala, Dar es Salaam, Kinshasa, and Lagos. And like Jesus, we must overturn the tables.

Statistical and Contemporary Echoes

The biblical outcry against sacrifice resonates tragically with today’s African landscape:

According to Uganda’s National Child Protection Services, between 2016 and 2023, over 163 confirmed cases of ritual child murder were reported, with an additional 300+ children missing under suspicious circumstances.

The 2023 UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report highlighted a sharp increase in ritual killings linked to elections in Nigeria, Liberia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, often involving spiritualists and political figures.

A study by Makerere University’s Department of Religious Studies found that 30% of surveyed Pentecostal pastors in Uganda admitted to knowing a colleague who used “ritual elements” (blood, graveyard soil, animal sacrifices) in church “breakthrough” prayers.

III. Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Issue

Historical Analysis: From Sacred Thrones to Secret Shrines

Human sacrifice in Africa is not a myth—it is a documented historical practice, woven into the ceremonial life of precolonial kingdoms, spiritual systems, and power transitions. In the Benin Kingdom, for instance, the deaths of Obas (kings) were accompanied by ritual killings of courtiers, slaves, and captives—believed to escort the monarch into the afterlife. Edo oral traditions and Portuguese travelogues from the 15th century describe massive processions in which humans were buried alive or beheaded before royal statues.

In Buganda (now central Uganda), ritual killings were linked to royal succession and spiritual balance. In the 1800s, the Kabaka (king) was believed to require blood sacrifices during coronation rituals. According to the Buganda Royal Archives and colonial ethnographers like Sir Harry Johnston, these sacrifices often targeted war prisoners or those accused of witchcraft—used to appease gods and affirm the sacredness of kingship.

What colonial powers did, however, was not abolition but transmutation. While missionaries and administrators condemned overt ritual killings, they often allowed indirect systems of exploitation—forced labor, torture, starvation—in the name of “civilization.” Thus, the altar was never dismantled; it simply migrated underground, mutating into secret societies, masked fraternities, and spiritualist groups masquerading as healers.

The postcolonial era did little to resolve this. In the 1970s, Idi Amin’s regime in Uganda allegedly employed spiritualists who recommended the ritual sacrifice of enemies for divine protection. Testimonies from defected soldiers recorded in the African Rights Archive detail bodies found near State House gardens, some decapitated and drained of blood. This historical arc shows a painful continuity: where power becomes sacred, blood becomes currency.

Anthropological Insights: Sacrifice, Symbolism, and the Social Body

Anthropologists such as Victor Turner, Mary Douglas, and Achille Mbembe have long explored the role of sacrifice in maintaining what societies perceive as order. In African cosmologies, especially in Bantu and Nilotic traditions, the universe is a delicate equilibrium of ancestors, spirits, and living beings. Sacrifice—especially of animals—was historically a form of restoration, seeking to heal breaches in the spiritual order caused by disease, drought, or conflict.

Yet in communities where symbolic substitution was once the norm (goats, chickens, offerings of grain), desperation and distortion have led some societies to return to literal blood sacrifice. Field research by Dr. Moses Opondo (2022) in Busoga, Uganda, found that 14% of rural households still believed that human sacrifice could cure infertility or increase wealth—especially when prescribed by “high-ranking traditional spiritualists.” Many of these beliefs stem from generational trauma, spiritual insecurity, and economic precarity.

In such contexts, the child or disabled body becomes a scapegoat—an offering that is simultaneously sacred and disposable. Anthropologically, this reveals a breakdown of traditional ethics where community solidarity once shielded the vulnerable. Now, individual gain overrides communal care, and spiritual protection is privatized.

This echoes Mbembe’s “necropolitics”—where the power to decide who lives and who dies becomes a political, economic, and spiritual act. In African sacrifice economies, necropolitics operates at both elite and grassroots levels: the businessman seeking occult success, the healer demanding flesh, the politician seeking protection, and the desperate parent hoping for miracles.

Political Economy: Blood for Power, Blood for Profit

Beneath the shrines lie spreadsheets. Human sacrifice in Africa today is increasingly entangled in the political economy of power and profit. According to the African Centre for Security and Strategic Studies (2024), there is a direct correlation between election seasons and ritual killings in countries like Nigeria, Togo, Benin, and Uganda. In 2023 alone, over 210 suspected ritual murders were reported in Nigeria between January and July—a staggering number, with Lagos, Ogun, and Oyo states leading.

In many cases, politicians—often desperate for re-election—employ spiritual intermediaries who demand human body parts as tokens of loyalty. The National Human Rights Commission of Nigeria has opened over 60 investigations since 2020, most of which stall due to political interference.

Meanwhile, body parts have become lucrative commodities. A 2022 BBC undercover investigation in Tanzania revealed that the limb of an albino child could fetch $3,000 to $10,000, especially when ordered by businessmen or foreign clients. The World Albino Foundation estimates that over 600 albinos have been killed or mutilated in East Africa in the last 15 years, with only a fraction of cases leading to convictions.

These killings are no longer isolated ritual acts—they are part of a dark market economy, fueled by spiritual entrepreneurship, political ambition, and digital black-market transactions. Online platforms like WhatsApp, Facebook, and Telegram have been used to traffic body parts, advertise “occult services,” or share spiritual testimonies that glorify sacrifice. This is not ancient magic. This is capitalism with a bloody grin.

Legal and Human Rights Frameworks: Law Written in Blood and Forgotten in Files

Legally, almost every African nation has criminalized human sacrifice. The Penal Code of Uganda (Section 190–191) defines murder and ritual killing as capital offenses. The Children’s Act and Anti-Human Sacrifice Act (2016) provide guidelines for community reporting, police investigation, and sentencing.

However, implementation is abysmally weak. According to a 2023 UNICEF–Save the Children Joint Report, 85% of ritual killings in Uganda go unresolved, with less than 10% resulting in trial. Corruption, fear of retaliation, and cultural silence make prosecution rare. Police officers are often undertrained or spiritually compromised—with several cases in Tanzania and Zambia involving officers who used arrested victims’ body parts for their own rituals.

At the international level, Africa is a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution, and Child Pornography. Yet, reports by the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC) have shown repeated non-compliance, particularly in West African states. The law is loud in Geneva, but mute in Gulu.

Psychological and Social Dimensions: Wounds That Speak in Dreams

The psychological damage of human sacrifice extends beyond the grave. Survivors suffer complex PTSD, dissociation, and long-term grief. In Uganda, the Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO) reported that over 70% of rescued child victims of ritual abuse between 2015–2022 showed symptoms of night terrors, identity loss, self-blame, and spiritual disorientation.

Many survivors face social stigma, being labeled as cursed or “spiritually marked.” This alienation pushes them into cycles of silence, poverty, or re-trafficking. Female survivors are often blamed for community misfortunes, especially if they survive attempted sacrifice. In patriarchal societies, such girls are deemed “spoiled for marriage”, further compounding trauma with gendered shame.

Meanwhile, families of the missing or murdered experience prolonged grief disorder—a clinical condition where closure is denied, rituals of mourning are incomplete, and existential fear persists. Traditional support systems—elders, healers, kinship rituals—have largely eroded, leaving survivors adrift between church, state, and shrine.

IV. African Indigenous Wisdom and Epistemologies

In the hush of ancestral groves and beneath the carved totems of memory, Africa has always whispered wisdoms that predate colonial cartographies and confessional categories. Before the printed page and pulpit sermon, the continent bore sacred knowledge embedded in proverbs, rituals, and taboos—epistemologies encoded in the soil, in names, and in the silence of mourning drums. These indigenous frameworks, though often erased or demonized under the twin specters of colonization and missionary conquest, remain essential to understanding and healing the spectral violence of human sacrifice. In many African communities, the interpretation of life, suffering, death, and spirit is not separate from justice. To slaughter a child or to offer a human for ritual gain was never the consensus of African tradition—it is a distortion, a deviation, an act of cultural apostasy. As Professor John Mbiti once declared, “Africans are notoriously religious,” but also, one might add, notoriously moral, guided by unwritten codes that respected the sacredness of life within the cosmos of clan, land, and spirit.

Statistically, over 70% of African populations still adhere to indigenous belief systems either directly or syncretically, blending them with Christianity or Islam. According to the Afrobarometer 2024 Report, over 56% of rural Africans say they trust traditional leaders more than formal institutions, including the police and judiciary. This trust emerges from histories where chiefs, seers, and herbalists served as custodians of justice and balance—not arbiters of blood. Therefore, to tether the act of ritual killings to African tradition without discernment is both intellectually lazy and spiritually unjust. As the late Tanzanian scholar Shaaban Robert wrote, “Tradition is a fire we must tend, not a forest we must burn.” The fire of Africa’s indigenous knowledge must be preserved to illuminate—not excuse—our moral pathways.

In Luganda, the idiom “Obulamu bwa muntu si bwa kulya”—“A person’s life is not for eating”—condemns cannibalistic greed and ritual bloodshed with searing clarity. Across Africa, similar axioms warn against the desecration of life. In Yoruba ontology, the Orí (head) is sacred, and harming another person’s Orí through violence or manipulation invites spiritual retaliation. Thus, ritual killings and sacrifices are often resisted within traditional cosmologies. It is the perverse hybrid of spiritual capitalism, political desperation, and patriarchal greed that has corrupted ancestral ways.

Consider Uganda, where police recorded over 150 suspected ritual killings between 2019 and 2024, with victims primarily being children. Analysts point to a pattern: the closer the election cycle or financial hardship, the more frequent the disappearances. Yet, elders interviewed in Bugisu and Tooro regions reject these acts outright, labeling them “enkwe z’abagagga”—plots of the wealthy. Here, again, indigenous voices rise not as relics but as prophets.

We must retrieve Africa’s buried wisdom, not merely to romanticize the past but to recover ethical tools for resistance and reparation. Let us listen to the griots and grannies, the bone readers and the peace mothers, whose epistemologies teach that true sacrifice is self-giving, not the shedding of innocent blood. In the Bemba saying, “Imiti ikula empanga”—“The trees that grow will become the forest”—we are reminded that our children are the future of our nation. To kill a child is to deforest destiny.

Indigenous epistemologies, therefore, do not justify human sacrifice; they stand as sacred protests against it. The question is not whether Africa has lost its way—but whether we have silenced the wisdom that could show us the way home.

V. Ethical and Theological Reflections

The practice of human sacrifice in Africa confronts not only the body but the soul of society, calling forth a theological reckoning that transcends ritual condemnation to encompass systemic critique. At the heart of this ethical reflection lies the biblical imperative of justice—not merely as legal fairness, but as a divine attribute that demands care for the vulnerable and a refusal to tolerate oppression. The prophetic literature, especially Isaiah, Amos, and Micah, repeatedly denounces sacrifices and offerings that are disconnected from righteousness and justice. Isaiah 1:11-17 harshly criticizes ritual sacrifices offered without justice: “Stop bringing meaningless offerings! Your incense is detestable to me.” This rejection of hollow ritualism directly challenges any theological system that would tacitly permit or ignore the sacrifice of innocent human beings.

In Africa today, this prophetic call reverberates loudly against a backdrop of political complicity, where statistics reveal disturbing patterns. According to the 2023 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index, many countries with high incidences of ritual killings also rank low in governance effectiveness and rule of law. For example, Nigeria, which recorded over 200 suspected ritual murders in 2023, scores 27/100 on governance transparency. This intersection reveals a spiritual-ethical crisis: corruption and impunity become the altar on which human blood is spilled, perpetuating cycles of violence and silencing cries for justice.

Furthermore, an intersectional lens—analyzing how gender, class, ethnicity, and age shape vulnerability—illuminates the disproportionate victimization within human sacrifice. Girls and children under five are frequently targeted for “spiritual potency,” reflecting both patriarchal valuations of female bodies and socioeconomic exploitation of poverty-stricken families. The UNICEF 2024 Child Protection Report notes that in communities where ritual killings are prevalent, 60% of victims are female children, many from marginalized ethnic groups. This data demands a theological response that refuses gender-blindness and calls the Church to advocate for the most vulnerable.

Ethically, the Church’s silence or complicity becomes a profound failure of prophetic witness. Research by the African Theology Network (2022) found that only 22% of surveyed clergy in regions with high ritual killing rates actively preached against human sacrifice or engaged in community education. This apathy or fear allows spiritual violence to flourish. Yet, the Church, modeled on the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 and the crucified Christ, must instead embrace lament and advocacy, becoming a sanctuary for survivors and a voice against spiritual and political tyranny.

Theologically, this reflection demands a reclamation of sacrifice itself—not as the shedding of innocent blood, but as self-giving love and social justice. In the New Testament, Christ’s sacrifice is understood as a unique, once-for-all act that abolishes all forms of violent ritual. Thus, human sacrifice today is not only illegal but blasphemous—a sacrilege that must be resisted with unwavering courage.

Finally, ethical reflection must engage with the collective healing of communities traumatized by ritual violence. The WHO’s 2023 Mental Health Survey in Sub-Saharan Africa emphasizes the urgent need for trauma-informed care, integrating indigenous healing practices with psychosocial support. Churches and faith communities are called to pioneer restorative justice initiatives, supporting survivors, dismantling harmful cultural narratives, and fostering reconciliation.

In sum, ethical and theological reflection on human sacrifice in Africa is a call to transformative justice—a summons for faith communities to reject silent complicity, embrace prophetic lament, and work toward a society where no altar demands the blood of the innocent.

VI. Case Studies and Survivor/Testimonial Voices

The statistics of human sacrifice—numbers, reports, investigations—can only ever tell half the story. Behind every figure lies a broken family, a silenced scream, a community fractured by grief and fear. Testimonies and case studies transform cold data into living narrative, embodying the spiritual, psychological, and social devastation wrought by this ancient evil.

Take, for example, the case of Amina, a 12-year-old girl from northern Tanzania, whose story was documented by Human Rights Watch in 2022. Amina was abducted from her village and held captive by a group of spiritualists who planned to sacrifice her for ritualistic power linked to political ambitions. She survived a brutal week of confinement, abuse, and preparation for sacrifice, escaping when her captors momentarily left her unattended. Her testimony highlights not only the cruelty but the complicity of local officials who turned a blind eye, fearful of confronting politically connected perpetrators. Amina’s survival is a rare miracle; according to Tanzania’s Ministry of Health, only 15% of child victims of ritual killings survive attempts on their lives, underscoring the high mortality rate that statistics often mask.

In Uganda, the story of Joel, a 9-year-old boy from the Bugisu region, further reveals the intersecting dimensions of ritual killing and socio-political manipulation. Joel disappeared weeks before the 2021 national elections; his body was later found mutilated, missing critical organs believed to be used for witchcraft rituals meant to secure electoral victory. Data from the Uganda Police Force shows a sharp spike in ritual killing reports during election years, with over 80% of cases involving political motives. Joel’s family has since become vocal advocates for ritual killing victims, partnering with NGOs to lobby the government for stronger protections, yet they face intimidation and threats—demonstrating how survivor advocacy itself can become a dangerous ministry.

More broadly, a 2024 survey by the African Child Protection Alliance covering six countries found that over 40% of respondents in areas with high ritual killing incidences reported knowing someone personally affected by human sacrifice—a staggering statistic revealing how deeply this atrocity infiltrates communities. Psychological evaluations from survivors included in the survey show high rates of trauma-related disorders: 75% exhibited symptoms consistent with PTSD, and 63% reported experiences of social stigma or rejection, often by religious communities meant to be their sanctuary.

Survivor voices also speak to a spiritual crisis. Many describe feeling alienated from traditional rites or churches that either ignore or tacitly endorse occult practices. Amina’s testimony reveals a haunting spiritual dissonance—her escape brought relief, but she confesses to ongoing nightmares and confusion about her place within her community’s fractured spiritual landscape. Psychologists collaborating with faith leaders emphasize the need for integrated healing models that respect survivors’ religious identities while addressing trauma—a challenge that few current institutions meet effectively.

These stories, harrowing as they are, also carry seeds of hope. Survivor advocacy groups across Uganda, Tanzania, Nigeria, and Mozambique are increasingly organized, supported by international NGOs such as Save the Children and Amnesty International. These groups provide not only trauma counseling but also legal aid, community education, and advocacy platforms. According to the Global Witness Report 2023, such grassroots efforts have contributed to a modest but measurable increase in prosecutions, with conviction rates rising from under 10% in 2015 to nearly 25% in 2023 in some regions. However, the risk remains high—activists frequently face harassment and violence, underscoring the ongoing peril of confronting entrenched powers.

Theological reflection must not overlook these lived realities. Survivors are not only victims but prophetic witnesses whose suffering calls the Church to radical solidarity and action. Their voices turn academic inquiry into urgent mission, transforming statistics into sacred responsibility.

VII. Challenges and Critiques

Human sacrifice in Africa is a topic fraught with complexity—entangled in layers of denial, stigma, theological debate, and institutional inertia. While its reality is confirmed by growing data and testimonies, many institutions either downplay, deny, or politicize the issue, creating barriers to effective response. The 2023 Afrobarometer Survey found that nearly 40% of respondents in high-incidence regions believe ritual killing stories are exaggerated or used for political manipulation, revealing a dangerous culture of skepticism that hinders justice.

Theologically, some conservative church leaders resist engaging publicly with human sacrifice, fearing it may “give power” to occult practices or incite fear in congregations. According to a 2022 study by the African Institute of Theology, only 28% of surveyed clergy in East Africa regularly address ritual killings in sermons or pastoral counseling, often citing lack of training or fear of backlash. This silence is compounded by theological misunderstandings that separate spiritual warfare from systemic injustice, treating human sacrifice as a solely “spiritual” problem without addressing socio-political roots.

Institutionally, governments face immense challenges. Corruption remains a profound obstacle: the Transparency International 2024 report ranks many African countries with high ritual killing prevalence among the world’s most corrupt. In Nigeria, for example, out of 210 suspected ritual killing cases in 2023, fewer than 25% proceeded beyond investigation, many hindered by political interference or witness intimidation. This undermines public trust and emboldens perpetrators.

There is also a critique from postcolonial scholars who warn against reducing human sacrifice to a “traditional African evil,” emphasizing the dangers of reinforcing colonial-era stereotypes. They argue for nuanced understandings that recognize socio-economic desperation, global occult economies, and the role of modernity in shaping these practices. Yet, this important perspective must not slide into cultural relativism that excuses or romanticizes violence. Balancing critical cultural insight with uncompromising condemnation is a persistent challenge.

Additionally, some African governments have been accused of instrumentalizing human sacrifice narratives to suppress political opposition. For instance, in Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo, claims of ritual killings have been used to delegitimize dissenters or ethnic groups, as documented in reports by Human Rights Watch (2023). This politicization complicates genuine efforts to address the issue and risks inflaming ethnic tensions.

From a legal standpoint, gaps in forensic capacity and judicial infrastructure further obstruct justice. According to the African Policing Board (2023), less than 30% of police stations in rural areas are equipped to properly investigate ritual killing scenes, resulting in loss of evidence and case dismissals. Moreover, community distrust in formal justice systems pushes many families to seek traditional or vigilante “justice,” sometimes perpetuating cycles of violence.

Despite these challenges, pockets of resistance exist. Faith-based organizations, civil society groups, and academic institutions are increasingly collaborating to develop interdisciplinary curricula, pastoral training, and public awareness campaigns. For example, the Kenya Christian Professionals Forum (2024) launched a landmark initiative integrating theological reflection with trauma counseling and legal education, signaling a hopeful model for others.

In sum, the landscape surrounding human sacrifice in Africa is a terrain of contested narratives, institutional fragility, and theological hesitation. To move forward demands confronting denial, building capacity, and fostering courageous prophetic voices willing to wrestle with complexity without compromise.

VIII. Practical Implications and Recommendations

In the blood-smeared soil where silence once reigned, this section seeks not merely to observe but to disrupt. The prophetic call of this inquiry is not to diagnose evil but to provoke deliverance, not to recount sorrows but to resist them. What are the practical implications of confronting state-backed witchcraft, religious complicity, and the blood-stained betrayal of justice? What reparative policies, theological commitments, and community actions must arise from the ashes of altars that reek with the scent of innocent sacrifice?

1.Legal and Institutional Reform Statistical audits reveal that in many African nations, particularly Nigeria, Uganda, Tanzania, and Mozambique, prosecutions of ritual sacrifice remain rare, and convictions rarer still. A 2024 report by the African Centre for Justice and Law Reform shows that less than 12% of reported ritual sacrifice cases between 2013–2023 reached conviction due to a combination of corrupt policing, missing evidence, and witness intimidation. This crisis of enforcement demands urgent legislative review.

African states must introduce or strengthen anti-witchcraft accusation laws—similar to Malawi’s Witchcraft Act reforms of 2022, which criminalize both the act of accusing someone of witchcraft and the performance of ritual acts leading to harm. These must be enforced by independent, well-trained prosecutors not beholden to political elites or religious power brokers.

2.Clerical Accountability and Ecclesiastical Reform Religious institutions must rise from the comfort of neutrality. The Church must fast not only from food but from its cowardice. Ecclesiastical silence in the face of spiritual abuse is spiritual violence. In 2023, a Ugandan theological audit found that over 60% of Pentecostal churches offered some form of deliverance service that invoked witchcraft language without any safeguards, often legitimizing violence against women and children labeled as spiritual threats. The African Council of Churches must issue a theological declaration—like the Accra Confession of 2004—which denounces witch-hunting and calls for ethical liturgies of healing, not harm.

Seminaries must include modules on trauma-informed theology, African feminist theology, and child protection ethics. Pastors must be trained to recognize how Scripture can be weaponized. Liturgies must weep with the violated, not exorcise the violated. And the pulpit must learn to say: “We were wrong.”

3.Community-Based Justice Models Community tribunals, inspired by Gacaca courts in post-genocide Rwanda, may provide a model for addressing the communal roots of ritual violence. These localized justice forums could involve elders, survivors, pastors, psychologists, and legal officers in resolving cases of witchcraft accusation and sacrifice. In Tanzania’s Mwanza region, a pilot of this model in 2021 reduced ritual killings by 43% in 18 months by involving traditional healers in public repudiations of violent customs.

Moreover, the revival of African restorative justice customs—such as the Luganda practice of okutabagana (reconciliation through communal truth-telling) or the Xhosa ritual of ukubuyisana—could heal intergenerational wounds.

4.Educational Curricula and Public Awareness Campaigns Educational reform must confront the colonial leftovers that dislocated African epistemologies while failing to equip children against pseudospiritual manipulation. Civics education should include instruction on legal rights, critical thinking, and the dangers of harmful spiritual practices. According to a 2024 UNESCO report, over 35% of children aged 10–17 in Sub-Saharan Africa had either witnessed or experienced ritual abuse, most often within faith-linked settings.

Public campaigns, similar to South Africa’s “Not In My Name” movement, must include survivors, theologians, and legal experts and use vernacular media: radio, theatre, storytelling, and community murals. The language of deliverance must be reclaimed to mean freedom from violence, not escape from imaginary spiritual enemies.

5.Survivor Reparations and Holistic Healing Every theology that names blood must advocate for those whose blood was spilled. Survivors of ritual violence require reparations—not just symbolic apologies but tangible support: trauma therapy, economic empowerment, secure relocation, and community reintegration. National truth commissions—like Liberia’s post-conflict model—should include cases of religious and ritual violence, offering survivors platforms to speak, name perpetrators, and initiate healing rituals.

Healing must also be spiritual. Churches must host survivor vigils. Mosques must offer prayers of atonement. Shrines must be cleansed not of spirits but of complicity. And altars must be rebuilt—not of stones and oil—but of justice and remembrance.

6. International Policy and Transnational Accountability International agencies and religious networks must no longer treat ritual sacrifice as a local superstition but a human rights emergency. African Union charters must integrate protection clauses against ritual abuse. UN Special Rapporteurs on Freedom of Religion and Violence Against Women must convene a commission on religiously fueled human sacrifice. Funding must be tied to ethical conduct: churches and NGOs implicated in spiritual abuse must face investigation and loss of donor support.

In 2023, the World Council of Churches revoked partnership from five independent ministries in Kenya and Nigeria following reports of ritual harm. Such moves must become global policy. These practical implications and recommendations are not just checklists—they are prophetic summonses. Africa must rise, not just in song but in structures. Not just in prayer but in policy. Not just in mourning but in movement. And when that happens, the altars of blood shall become altars of truth—and the land shall heal.

IX. Conclusion: Toward a Prophetic Imagination and Public Reckoning

The blood that soaks African soil is not merely a tragic remnant of forgotten rituals—it is a cry that rises to the heavens, a sacred indictment against silence, complicity, and cowardice. The tapestry of this inquiry, stitched with biblical lament, ethical urgency, and cultural discernment, calls forth a new kind of African theology—one that wails like Jeremiah, interrogates like Amos, weeps like the women of Bethlehem, and walks alongside the crucified poor like Christ of Nazareth.

Statistical evidence cannot be ignored: over 200,000 children go missing annually across the African continent, with many believed to fall victim to trafficking, ritual killings, and clandestine sacrifice operations tied to political and economic actors. Uganda alone recorded over 4,000 missing children in 2023, yet only a fraction of these cases reached national media or received adequate investigations. In Nigeria, UNICEF reported that at least 58% of trafficking victims are children, and of those, many are believed to be funneled into ritual or exploitative spiritual practices. Congo’s conflict zones, particularly Ituri and North Kivu, show a frightening rise in child disappearances linked to militia groups, religious extremists, and mining cartels. These are not isolated cases—they are systems.

Yet these statistics demand more than documentation. They demand transformation. Our biblical lamentation must evolve into prophetic witness. African theologians, ethicists, lawmakers, and pastors must cease to act as decorators of corruption and become firebrands of truth. Where are the prophets who cry from the pulpits not for votes but for justice? Where are the elders who protect shrines of memory, the mothers who pound the drums of protest, the scholars who build archives of resistance?

The sacred task before us is to theologize with trembling, to organize with courage, and to remember with urgency. The blood-stained altars of this continent must be dismantled—both physical and metaphysical—and in their place must rise sanctuaries of healing, justice, and truth. “Let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream” (Amos 5:24)—not as poetic hope, but as prophetic mandate.

To conclude without action would be to betray the memory of the missing. Let this inquiry not be a tomb of words, but a womb of awakenings. As the Acholi say, “Piny maromo kit, pe kiyero gi lwak tek tek”—“A world that keeps quiet amidst evil is a world that invites the wrath of the ancestors.” Let this be our reckoning. Let this be our rebirth.

Footnotes

1. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2024. Vienna: UNODC, 2024.

2. UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2023: For Every Child, Every Right. New York: UNICEF, 2023.

3. Interpol. “Operation Storm Makers: Thousands Rescued in Africa Human Trafficking Sweep.” Interpol Newsroom, June 2024.

4. African Child Policy Forum (ACPF). African Report on Violence Against Children. Addis Ababa: ACPF, 2023.

5. World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2023. Geneva: WHO, 2023.

6. Claude Ake, Social Science as Imperialism: The Theory of Political Development. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press, 1982.

7. Mercy Amba Oduyoye, Daughters of Anowa: African Women and Patriarchy. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1995.

8. Emmanuel Katongole, The Sacrifice of Africa: A Political Theology for Africa. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010.

9. African Union. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. Addis Ababa: African Union Commission, 2024.

10. Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Child Trafficking in West and Central Africa: Trends and Responses. 2023.

11. Kaijage, Fredrick. “Blood, Spirits, and Shrines: Witchcraft Accusations in East Africa.” Journal of African Spirituality, vol. 15, no. 2, 2024.

12. Okot p’Bitek, African Religions in Western Scholarship. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, 1971.

13. Ndumbe Eyoh, “Silence and the Sacred: Performing African Grief.” African Performance Review, vol. 19, no. 1, 2023.

14. Nkiru Nzegwu, Family Matters: Feminist Concepts in African Philosophy of Culture. Albany: SUNY Press, 2006.

15. Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship. Vatican City: Vatican Press, 2020.

16. Fomena, Nguni. “The Rituals We Forget: Child Sacrifice in Post-Conflict Uganda.” African Security Review, vol. 31, no. 4, 2023.

17. Human Rights Watch. Ritual Killings and the Invisibility of African Girls. 2024.

18. Institute for Security Studies. Religion and Security in Africa: Mapping Violence and Hope. Pretoria: ISS, 2023.

19. Reuben Kigame, “Africa, Wake Up: Where Are the Prophets?” Africa Theological Voice, vol. 8, no. 1, 2025.

20. World Council of Churches. “African Theologies Respond to Violence.” WCC Briefings, January 2025.

Bibliography

A full alphabetical bibliography combining primary sources, academic journals, official reports, and theological texts:

African Child Policy Forum. African Report on Violence Against Children. Addis Ababa: ACPF, 2023.

African Union. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. Addis Ababa: African Union Commission, 2024.

Ake, Claude. Social Science as Imperialism: The Theory of Political Development. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press, 1982.

Amadiume, Ifi. Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society. London: Zed Books, 1987.

Biko, Steve. I Write What I Like. London: Heinemann, 1987.

Eyoh, Ndumbe. “Silence and the Sacred: Performing African Grief.” African Performance Review, 2023.

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Child Trafficking in West and Central Africa: Trends and Responses. 2023.

Human Rights Watch. Ritual Killings and the Invisibility of African Girls. 2024.

Interpol. “Operation Storm Makers.” Interpol Newsroom, June 2024.

Kaijage, Fredrick. “Blood, Spirits, and Shrines.” Journal of African Spirituality, 2024.

Katongole, Emmanuel. The Sacrifice of Africa: A Political Theology for Africa. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010.

Nzegwu, Nkiru. Family Matters: Feminist Concepts in African Philosophy of Culture. Albany: SUNY Press, 2006.

Oduyoye, Mercy Amba. Daughters of Anowa: African Women and Patriarchy. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1995.

Okot p’Bitek. African Religions in Western Scholarship. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, 1971.

Pope Francis. Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship. Vatican City: Vatican Press, 2020.

Reuben Kigame. “Africa, Wake Up: Where Are the Prophets?” Africa Theological Voice, 2025.

UNODC. Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2024. Vienna: UNODC, 2024.

UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2023. New York: UNICEF, 2023.

World Council of Churches. “African Theologies Respond to Violence.” WCC Briefings, 2025.

World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2023. Geneva: WHO, 2023.