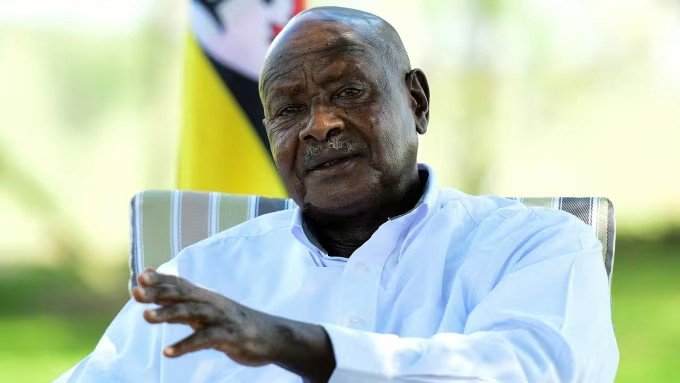

Yoweri Kaguta Museveni

By Isaac Christopher Lubogo

There are moments in political history when victory ceases to be a matter of contest and becomes an instrument of arithmetic. Uganda stands at such a juncture. The theatre of democracy, once intended to test competing visions of the nation, has become a ritual reaffirmation of a preordained supremacy. The opposition’s disarray, the ruling party’s mastery of the levers of state, and the deliberate architecture of control have converged to create what may well be President Museveni’s most emphatic triumph — not merely by votes, but by design.

1. The Geometry of Power: When the State Becomes the Party

To understand Uganda’s political reality, one must first distinguish between government, state, and party. In mature democracies, these are separate entities — distinct in purpose and in spirit. In Uganda, they have fused into a single organism. The ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) has effectively institutionalized itself within the bloodstream of the state; its survival is indistinguishable from that of the Republic itself.

Museveni has achieved what Machiavelli called “the perfection of governance through permanence.” The ministries, the local councils, the security organs, and even the electoral machinery echo one command, one rhythm, one central will. It is not tyranny of personality; it is the tyranny of structure.

Thus, every election becomes less about choice and more about continuity. The citizen votes not merely for a man, but for stability, employment, and the avoidance of uncertainty. The ballot has been weaponized into a psychological referendum on fear and survival — the two most effective instruments of political control.

2. The Opposition’s Tragic Incompetence: A Divided House Cannot Rise

If history were a courtroom, the Ugandan opposition would be found guilty of strategic negligence. It stands ideologically bankrupt, intellectually fragmented, and organizationally anaemic. While NRM operates as a unified state-machine with tentacles in every parish, the opposition operates as an archipelago of egos — disconnected, competing for visibility, not victory.

Each opposition leader seeks prominence over purpose.

They mistake noise for mobilization and crowds for structure.

They dominate hashtags but fail to dominate polling stations.

Worse still, many of their internal fractures are engineered from within. Agents provocateurs — moles camouflaged in reformist attire — infiltrate their ranks, seeding mistrust, funding splits, and leaking strategy. Uganda’s opposition today is a textbook study in political entropy: energy without organization, passion without direction, and courage without caution.

As a result, Museveni faces no real contender — only opponents. And as Sun Tzu reminds us: “He who fights many enemies, fights none.”

3. Institutional Capture: The Masterstroke of Longevity

The genius of Museveni’s political engineering lies not in his charisma, but in his institutional omnipresence. Over the decades, he has mastered the art of quiet infiltration — where loyalty is built not through ideology, but through livelihood.

The civil servant, the district officer, the soldier, and even the electoral official are all products of his political time. Their economic continuity is tied to his political continuity.

To remove Museveni, therefore, is to threaten entire bureaucratic ecosystems that have known no other political oxygen. This explains why every election becomes not a contest between candidates, but a referendum on continuity versus chaos.

As Montesquieu noted, “When the same hand controls both the sword and the law, freedom is an illusion.” Uganda’s political theatre thus becomes an elaborate illusion — constitutional in appearance, coercive in essence.

4. The Legal and Security Architecture of Control

Every regime sustains itself through what the Romans called instrumenta regni — instruments of rule.

In Uganda, these instruments are legal, military, and bureaucratic. Laws have been subtly adjusted to expand state discretion while shrinking civic space. Protests require permission that is never granted. Assemblies are lawful only for the loyal. Arrests are justified under the elastic doctrines of “public order” or “security concerns.”

The security apparatus, deeply embedded in political enforcement, operates with surgical precision: a strategic arrest here, a disruption there, a chilling message everywhere. No mass crackdown is needed; selective deterrence is enough. It is a politics of psychological governance.

By the time ballots are cast, the opposition is not merely weakened; it is pre-defeated.

5. The Mechanics of the 80%: When Numbers Reflect Power, Not Preference

An 80% electoral outcome is not merely a statistic; it is a statement — a mathematical sermon on authority. It communicates to both domestic and international audiences that resistance is futile, and continuity is ordained.

The formula is simple:

A disciplined rural mobilization network funded by state resources.

A media narrative that amplifies the incumbent’s inevitability.

Legal and administrative constraints that limit opposition reach.

Fear-induced apathy among dissenters.

The result is not the reflection of popular will, but of political physics: when all forces are aligned in one direction, the vector of victory is predetermined. The opposition may dominate discourse, but the regime dominates distribution — of power, of resources, and of votes.

6. The Paradox of Popularity: Between Legitimacy and Efficiency

Ironically, Museveni’s likely 80% will be both the apex of his efficiency and the nadir of his legitimacy. It will demonstrate the regime’s total mastery of the electoral machine while simultaneously confirming the death of genuine contestation.

The higher the number, the lower the authenticity. Yet the paradox is that most citizens, weary of confrontation and chaos, will still prefer stability to uncertainty. In this sense, the electorate has been conditioned to vote not for a leader, but for the absence of turmoil.

Thus, the election becomes a referendum on fatigue.

The people do not vote for Museveni — they vote against the unknown.

7. Comparative Lens: Uganda and the Politics of Managed Democracy

Across Africa, the rise of “managed democracies” — from Rwanda to Tanzania and Equatorial Guinea — illustrates a broader continental trend: the perfection of control under democratic veneers. Uganda has merely refined this model with greater sophistication.

International observers issue statements; domestic institutions issue results.

By the time analysis is written, legitimacy is already declared.

Uganda’s democratic decline, therefore, is not unique — it is textbook neo-authoritarianism, draped in constitutional fabric, sanctified by numerical majesty.

8. The Future Question: What Happens After the Apex?

Every mountain, no matter how high, ends in a descent. History teaches that regimes which over-consolidate power inevitably face a crisis of succession. The danger for Uganda is not Museveni’s victory — it is what follows his inevitability.

An 80% margin leaves no credible opposition in parliament, no legitimate debate in the public sphere, and no institutional resilience for transition. The very architecture that ensures his victory may become the architecture of national paralysis when he exits the stage.

As Aristotle warned: “That which is made absolute eventually consumes itself.”

Conclusion: The Mirror of a Nation

In truth, Museveni’s 80% is not a measure of his popularity — it is a mirror reflecting Uganda’s political condition. It reveals how deeply fear, dependency, and institutional capture have shaped the political soul of a nation once revolutionary.

The opposition has failed not because Museveni is invincible, but because they have yet to understand the philosophy of his survival.

He governs through strategic inevitability — a doctrine where perception, control, and longevity merge into one unbroken continuum.

Uganda’s 2026 election, therefore, will not be a battle of ballots but of narratives.

The incumbent will win — not because he is loved, but because he is unreplaceable by design.

And in that paradox lies both the brilliance and the tragedy of Uganda’s democracy.

“Democracy dies not with a gunshot, but with applause.”

— Lubogo, paraphrasing Tocqueville for the African century.