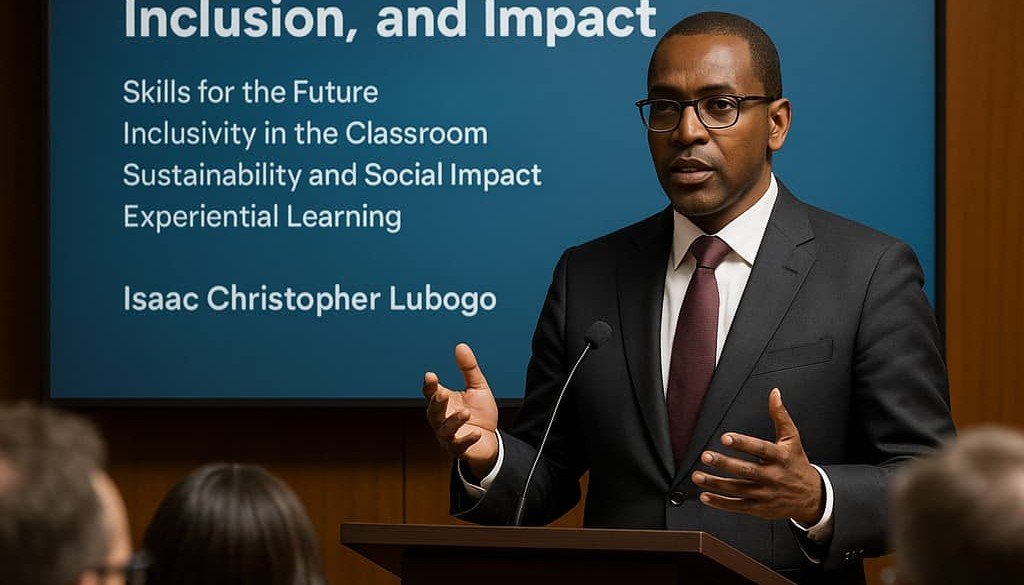

By. Isaac Christopher Lubogo

Legal Scholar | Consultant, SuiGeneris Legal Think Tank

(Panel Presentation for “The Future of Legal Education in East Africa: Innovation, Inclusion, and Impact”)

7 August 2025

Opening Reflection: What if the Next Great Lawyer Never Makes it to Law School?

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Let me begin with a thought experiment.

Imagine a girl in Karamoja. She speaks three languages, negotiates daily with livestock raiders, understands land, drought, and kinship law—but cannot read a single line of Blackstone. Now, imagine she is the greatest legal mind her generation will never meet, because our systems never considered her part of the legal education equation.

That is the scandal of our current model.

We’ve mistaken intelligence for English, competence for credentials, and justice for access to the courtroom.

So today, I don’t speak to impress. I speak to disrupt.

I. The Tragedy of the “Successful” Law Graduate

Let me ask you: What happens when a legally educated person has all the answers to exam questions… but no questions about injustice?

We’ve taught generations to recite the law but not to question its morality. To quote Noam Chomsky:

> “The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow lively debate within that spectrum.”

Law schools in East Africa have mastered this technique. We’ve produced the most articulate defenders of broken systems. Our graduates speak French fluently in a burning house.

II. Why Sustainability Must Begin in the Lecture Room

We often think of sustainability in terms of climate or energy. But what about intellectual sustainability? Moral sustainability? Civic sustainability?

Ask yourself: Can a society be sustainable when its lawyers are trained to chase billable hours over public good?

Legal education must embed three forms of sustainability:

1. Intellectual Sustainability:

Do our graduates have the capacity to adapt to legal disruptions—AI, climate litigation, digital identity?

> A lawyer who cannot update their thinking is a liability, not an asset.

2. Moral Sustainability:

Are our students learning to critique unjust laws, or simply apply them skillfully? A legally trained human rights violator is more dangerous than an uneducated one.

3. Societal Sustainability:

Is the community better off because this lawyer was trained?

> In short: We need to move from teaching law as a tool of access—to law as a force of repair.

III. The Example of the Jerrican

Let’s make this plain.

When a child in rural Uganda is told to fetch water, what do they carry? A jerrican. Not because it’s beautiful, but because it’s practical.

The modern legal education system? It teaches us to carry a golden goblet… beautiful in form, utterly useless in function.

Our students graduate with Latin maxims and no local wisdom, citations of Lord Denning but no understanding of customary tenure systems.

We are producing lawyers who can quote Donoghue v Stevenson but cannot draft a land-sharing agreement for post-conflict Acholi communities.

> What use is a golden goblet when the people are thirsty for justice?

IV. Technology: The False God and the Real Tool

Everyone today talks about AI, digital learning, and the metaverse. But let’s be clear: Technology is not the revolution. Consciousness is.

If you put a broken system on the blockchain, you now have an automated injustice machine.

If your class is streamed but still alienating, you’ve digitized oppression.

So yes, let us embrace:

Open-source legal databases

Mobile legal aid platforms

Swahili court simulators

AI tutors for rural learners

But the real innovation is not the tool—it’s the intent.

> We must teach students not just how to use tools—but how to question the hands that build them.

V. The Grand Lie of Neutral Legal Training

Here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Legal education is not neutral. It never was.

The very structure of the curriculum—the cases we study, the language we privilege, the values we reward—are ideological battlegrounds.

Why do we teach company law in every university but neglect customary tenure?

Why are legal ethics one semester, and corporate law three?

This is not oversight. It is design.

To quote Paulo Freire:

> “There’s no such thing as a neutral education process. Education either functions as an instrument to bring about conformity or freedom.”

We must now teach law not as content, but as context, contestation, and construction.

VI. Purpose-Driven Pedagogy: What We Must Do Next

Let me be surgical. Here’s how we embed purpose:

1. Rewire the Curriculum

Infuse every subject with an SDG lens

Teach “Law and Social Imagination” alongside “Law of Contract”

Replace the Eurocentric canon with lived African case studies

2. Revalue Field Learning

Law students should spend time in refugee camps, land conflict zones, and community courts.

> One week in a displaced community will teach more law than a semester of moot court.

3. Rethink Assessment

Can students solve a legal problem for a market vendor or boda-boda rider?

Can they explain the Constitution in five local languages?

4. Restore African Philosophies of Justice

Ubuntu, Obuntu, Harambee, and Enkanyit must return to the classroom—not as decoration, but as doctrinal frameworks.

> If we teach only what colonialists taught us, we will only solve the problems they had.

VII. The Lawyer as a Midwife of Justice

In ancient African societies, midwives were revered not because they created life—but because they brought life safely into the world.

That is what a lawyer must become.

Not a legal technician. Not a legal celebrity. But a midwife of justice.

When the poor are bleeding, and the land is stolen, and the youth are jobless,

> Will your graduate stand as a midwife—or merely quote Article 26(2)?

Closing: What If…

What if every law school adopted a justice impact metric?

What if graduates had to defend a community before defending a corporation?

What if law was taught not just to be understood—but to be undone and rebuilt better?

To quote James Baldwin:

> “The purpose of education is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions… to ask questions of the universe, and then learn to live with those questions.”

Let that be our legal education.

Final Word

We do not need more lawyers.

We need lawyers who do more.

Not because they are told to.

But because they were taught to.

Thank you.

# Suigeneris