A Review by Isaac Christopher Lubogo

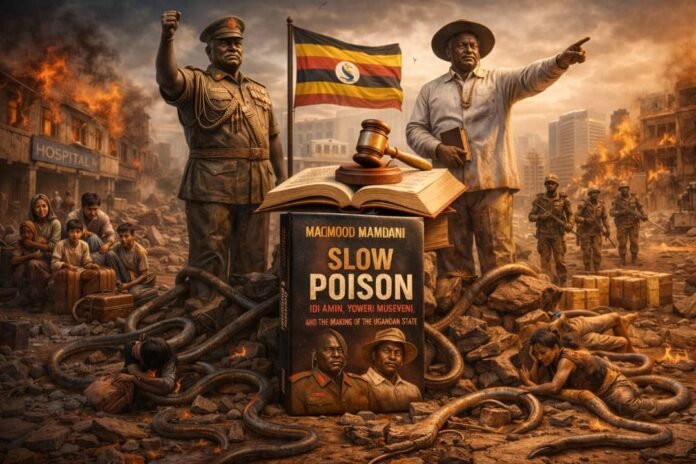

Author: Mahmood Mamdani

Publisher:

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Place of publication:

Cambridge, Massachusetts (and London, England)

Year of publication: 2025

1. Opening Position: Why This Book Matters — and Why It Is Dangerous If Read Lazily

Mamdani does not write to comfort; he writes to unsettle.

Slow Poison is not a biography of Idi Amin. It is not a conventional critique of Yoweri Museveni. It is not even, strictly speaking, a history book in the classical sense. It is a theory of the Ugandan state, told through lived experience, archival excavation, and sustained conceptual provocation.

The danger of the book lies precisely here: read lazily, it will be misunderstood as rehabilitation; read carefully, it is an indictment of structures, not personalities.

Mamdani’s central wager is bold: that Uganda’s postcolonial crises are not best explained by demonizing Amin or sanctifying Museveni, but by understanding how colonial statecraft—especially indirect rule—was inherited, modified, and normalized, producing what he calls a slow poison: harm that does not explode, but corrodes.

This is not a book about sudden collapse. It is a book about institutional decay that learns to survive.

2. Method and Voice: Why Mamdani Writes the Way He Does

One must begin by acknowledging Mamdani’s method, because many critics miss it.

He writes as:

a scholar of the colonial state,

a participant-observer shaped by exile and return,

and a theorist of belonging.

This is why the book oscillates between:

personal memory,

archival reconstruction,

political theory,

and institutional critique.

Those expecting neutral distance misunderstand Mamdani’s project. His argument is that distance itself is political. To pretend that Uganda’s history can be narrated without positionality is, in his view, already to side with power.

This explains the tone that unsettles many readers: Amin is not caricatured; Museveni is not moralized. Instead, both are situated within a continuity of state logic

3. Idi Amin: Not Innocence, But Context

The most controversial aspect of Slow Poison is Mamdani’s treatment of Idi Amin.

Let us be clear: Mamdani does not deny Amin’s brutality. What he refuses to do is allow brutality to function as an explanatory shortcut.

His argument is that Amin:

inherited a colonial army structured for repression,

ruled a state already organized around racialized citizenship,

and acted within a global Cold War order that rewarded certain violences while condemning others.

The chapters dealing with Asians—especially the distinction between the “good Asian” and the “bad Asian”—are crucial. Mamdani shows that the expulsion of Asians was not an irrational explosion, but a political act embedded in colonial racial hierarchies that had long positioned Asians as intermediaries and buffers.

This does not absolve Amin. It implicates the state form itself.

The reader who demands that Mamdani shout “Amin was evil” every ten pages misses the point. Mamdani is asking a harder question.

What kind of state produces rulers for whom mass exclusion appears as governance?

4. Transition and the Myth of Rupture

One of the book’s strongest contributions lies in dismantling the myth that Uganda experienced a clean break between Amin and what followed.

The chapters on the transitional period—particularly those dealing with exile, return, and what Mamdani memorably frames as “working above ground”—expose a grim continuity: the state changed hands, but not logic.

Violence did not disappear; it was redistributed.

Emergency did not end; it was normalized.

Belonging was not universalized; it was redefined.

This is where Slow Poison begins to bite hardest, because it refuses the comforting narrative that liberation movements automatically produce emancipatory states.

5. Museveni and the Reworking of Indirect Rule

Mamdani’s treatment of Yoweri Museveni is, in many ways, the most devastating—not because it is loud, but because it is structural.

The argument is not that Museveni is “worse” than Amin. The argument is that Museveni perfected what Amin improvised.

According to Mamdani:

Amin ruled through raw coercion;

Museveni rules through administrative fragmentation, culturalization of power, and managed inclusion.

The concept of “tribalizing the majority into minorities” is central here. Mamdani argues that under NRM rule:

ethnicity is not abolished,

it is institutionalized as governance technology.

Decentralization, cultural institutions, local councils, and security structures are read not as neutral reforms, but as mechanisms that diffuse responsibility while consolidating control.

This is not an argument about intentions. It is an argument about effects.

6. Neoliberalism, Knowledge, and the University

One of the most underappreciated sections of the book is the discussion of the World Bank and the transformation of the university.

Here Mamdani is at his sharpest.

He argues that:

neoliberal reform did not merely restructure the economy,

it restructured knowledge itself.

Universities ceased to be spaces of critical citizenship formation and became technical service providers. Political questions were reframed as managerial problems. Structural injustice was rebranded as capacity gaps.

This matters profoundly for Uganda, because it explains why:

policy failures are endlessly diagnosed,

but power is rarely interrogated.

The poison here is slow because it wears the mask of reform.

7. What the Book Gets Right — Unequivocally

Let me be explicit.

Slow Poison succeeds brilliantly in:

1. Demonstrating that Uganda’s crisis is structural, not episodic.

2. Showing that violence can be normalized without being spectacular.

3. Exposing how colonial logics survive independence through adaptation.

4. Challenging moralistic history that explains failure by pointing at villains rather than systems.

For anyone serious about understanding the Ugandan state, this book is unavoidable.

8. Where the Book Is Vulnerable — and Where I Push Back

And yet, the book is not beyond critique.

First, Mamdani’s structural lens sometimes flattens moral agency. While he is right to resist demonology, there are moments where individual responsibility risks being analytically underweighted.

Second, the lived suffering of ordinary Ugandans—especially victims of post-1986 state violence—sometimes appears more as evidence for theory than as subjects with their own moral claims.

Third, the book assumes a reader willing to sit with discomfort. In a political culture already prone to elite misinterpretation, this is a risk Mamdani knowingly takes.

These are not fatal flaws—but they are real tensions.

9. Why This Book Resonates with the Idea of “Slow Death” and Institutional Harm

Reading Slow Poison alongside debates on systemic iatrogenic failure (including in health, law, and governance) reveals its deeper relevance.

The book is ultimately about harm that is normalized:

harm without spectacle,

harm without clear perpetrators,

harm justified as necessity.

In this sense, Mamdani gives us a language to talk about death by design, not death by accident.

10. Final Verdict: A Necessary, Uncomfortable Book

Slow Poison is not a book you “agree with” or “disagree with” in total. It is a book you wrestle with.

It refuses:

easy villains,

easy heroes,

easy closure.

Its greatest achievement is that it forces Ugandans—and those who study Uganda—to confront a terrifying possibility:

that the problem is not who governs us,

but how we have learned to be governed.

That is why the poison is slow.

And that is why the antidote is not a regime change, but a reimagining of the state itself.