By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija– Emkaijawrites@gmail.com ,

Independent Researcher | Weaver of Stories and Truths

“Omuntu tayinza kulaba ku mukwano ng’alumwa ennyingo.”

“One cannot see love clearly while aching in the joints.” — Ugandan Proverb

Introduction

In the heart of many African homes, the kitchen and dining space function as sacred theatres where love, power, and ritual intertwine in a daily dance that shapes the rhythm of domestic life. These spaces are not mere sites of sustenance but are infused with cultural symbolism, emotional labor, and unspoken codes of respect and care. The choreography of preparing meals and sharing tea holds more than nourishment—it is a language of connection, negotiation, and identity. Yet when fixation takes hold—that relentless, unyielding adherence to a specific way of doing things—the fluidity of this dance hardens into a brittle formality, erecting invisible barriers rather than fostering intimacy. This study arises from a singular yet deeply revealing lived experience: after fasting throughout the day—a spiritual and physical discipline demanding patience and endurance—a husband returns home hungry and requests to eat before preparing tea, only to be met with refusal rooted in his wife’s fixation on the established tea ritual. This seemingly mundane domestic incident unmasks a profound dynamic where ritual overtakes empathy, and pride overshadows compassion, freezing communication and fracturing the warmth that marriage is meant to cultivate. Such moments, though small, mirror widespread tensions in African marriages, where fixation silently governs emotional expression and interaction to the detriment of relational health. By unpacking this tension, the essay seeks to illuminate fixation’s pervasive yet underrecognized role in undermining the delicate balance of African marital communication and connection.

Background and Context

Marriage within African societies transcends the mere legal or romantic union of two individuals; it is a communal covenant, deeply embedded in culture, tradition, and social expectation. Gender roles within these marriages are often clearly demarcated—men are traditionally cast as providers, protectors, and decision-makers, while women bear the responsibilities of nurturing the home, managing domestic affairs, and sustaining familial cohesion. These roles, though culturally revered and essential to social fabric, carry powerful unspoken expectations and emotional subtexts that shape daily behavior and interaction. Anthropological and sociological studies reveal that African marriages often function within an intricate web of duties and reciprocity, where silence, ritual, and symbolic acts communicate love and authority as much as spoken words do (Nnaemeka, 2019; Eze, 2021). However, contemporary African societies face rapid shifts due to urbanization, economic pressures, and evolving gender norms, challenging these traditional frameworks and introducing new tensions. Within this context, fixation emerges as a form of emotional rigidity—a stubborn adherence to ritual and routine that values form over function, process over people. The insistence on maintaining specific sequences in domestic rituals, such as serving tea before food, even when immediate physical needs dictate otherwise, illustrates how fixation transmutes cultural care into emotional coldness, creating silent fault lines within the home. This rigidity disrupts the necessary adaptability and empathy that underpin marital harmony, fostering relational distance and simmering conflict beneath the surface of daily life.

Research Problem

Across African marriages, emotional disconnects frequently manifest not in dramatic confrontations but through seemingly minor, ritualistic disagreements loaded with deeper meanings and unexpressed grievances. Fixation on particular routines or practices—such as the unyielding insistence that tea must precede food—can escalate minor domestic disagreements into significant relational strain and emotional withdrawal. Such behavioural patterns of rigid adherence and emotional inflexibility are often overlooked, normalized, or dismissed within both popular discourse and academic study, viewed as ordinary marital tensions or personality quirks rather than symptomatic of deeper issues. Yet, fixation functions as a covert disruptor that obscures genuine emotional needs, stifles open communication, and perpetuates implicit power imbalances within the marital relationship. Psychologists studying relational dynamics have identified fixation as a form of cognitive and emotional rigidity, which impedes empathy and fosters conflict (Ahmed & Nzewi, 2020; Mbiti, 2018). Despite its prevalence and impact, fixation remains underexplored in African marital studies, leaving a critical gap in understanding the nuanced emotional landscapes of marriage. Addressing this gap is essential for developing culturally sensitive frameworks for marital counseling, emotional literacy, and conflict resolution.

Significance of the Study

This study, rooted in a personal and culturally situated lived experience, aims to uncover the subtle yet powerful role fixation plays in shaping emotional dynamics and communication patterns within African marriages. By centering fixation as an analytical lens, the research contributes to a deeper understanding of how cherished cultural rituals—intended as expressions of love and respect—can transform into restrictive patterns that trap spouses in cycles of misunderstanding and emotional isolation. Recognizing fixation’s influence allows couples, counselors, and communities to identify when rituals cease to serve relational intimacy and instead become sources of contention and emotional withholding. Furthermore, this study intersects with ongoing discourses on gender roles, mental health, and emotional wellbeing in African contexts, emphasizing the urgent need to foster empathy, flexibility, and vulnerability within marital relationships. In a region where domestic conflicts are often kept private, and emotional expression constrained by cultural norms, illuminating fixation’s corrosive effects offers pathways toward healing and renewal. This exploration thus holds significance for both individual marriages and the broader societal project of nurturing resilient, loving African families.

Research Question

How does fixation on domestic rituals contribute to emotional conflict and communication breakdown within African marriages?

In what ways can increased awareness and understanding of fixation promote healthier relational dynamics, empathy, and flexibility between spouses?

Objectives

1.To analyze fixation as both a cultural and emotional phenomenon influencing marital interactions in African homes.

2.To examine the impact of fixation on empathy, communication, and power distribution within marital relationships.

3.To encourage reflective and dialogic practices that challenge fixation and promote emotional adaptability and vulnerability.

4.To offer culturally grounded recommendations and strategies for improving marital communication and emotional health, aiding couples in breaking free from fixation’s grip.

Thesis Statement

This essay contends that fixation—the rigid, unyielding adherence to specific domestic rituals despite evolving personal and relational needs—is a central yet often overlooked source of emotional conflict in African marriages. By examining fixation through the lens of a personal narrative, the study reveals how such emotional rigidity fractures communication, diminishes empathy, and deepens relational distance. It calls for increased emotional awareness, reflective dialogue, and cultural sensitivity as essential tools to restore the warmth, intimacy, and communal harmony that marriage is meant to nurture.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

The investigation of fixation within African marriages is best understood through the convergence of several interrelated theoretical perspectives, each shedding light on emotional rigidity, communication patterns, and culturally embedded relational dynamics. Attachment Theory, pioneered by Bowlby (1969), remains a cornerstone in explaining how early relational experiences shape adult intimacy and emotional responsiveness. Within this framework, fixation can be interpreted as a defensive mechanism that emerges when one partner experiences attachment insecurity—manifesting as a compulsive need to control rituals and routines to manage anxiety and maintain relational predictability. This perspective illuminates why ritualized behaviours, such as insisting on tea being served before food, may become inflexible efforts to create emotional safety or preserve perceived order in the relationship.

Complementing this is Bowen’s Family Systems Theory (1978), which conceptualizes the family as a complex, interdependent emotional unit in which individual behaviours affect and are affected by the whole system. Bowen highlights how families develop patterned interactions, including emotional cutoffs, triangulation, and rigidity, to maintain homeostasis. Fixation, in this light, is a systemic phenomenon that stabilizes relational dynamics—even when it comes at the expense of emotional health and individual needs. In African households, where extended family and communal connections often complicate marital roles, such rigidity can be particularly entrenched, fostering cycles of silence and unresolved conflict.

Moreover, Cultural Relational Theory (Jordan, 1991) situates these emotional dynamics within the broader socio-cultural fabric that informs African marriages. It emphasizes that emotional expression and communication are not universal but are deeply shaped by cultural narratives and gendered expectations. In many African contexts, traditional roles cast men as providers and decision-makers and women as caretakers and emotional anchors. These cultural scripts shape not only behaviours but also the interpretive frameworks partners bring to rituals and conflicts. Fixation, therefore, must be understood not only as an individual pathology but as a culturally inflected relational pattern, where communal values of respect, honor, and role adherence intersect with personal emotional needs. Together, these theories provide a multidimensional lens to analyze how fixation operates in African marriages, bridging psychological, systemic, and cultural domains.

Current State of Knowledge

Extensive scholarship on African marriages has explored gender roles, marital satisfaction, and conflict resolution mechanisms, revealing the complexity of intimate partnerships within culturally diverse contexts (Nsamenang & Tchombe, 2011; Amodu, 2019). These studies underscore how traditional roles assign men the responsibility of economic provision and protection, while women manage domestic affairs and nurture family cohesion, roles that carry implicit expectations about respect, communication, and emotional labour. However, research specifically addressing the nuances of emotional communication and the micro-dynamics of ritualized behaviour remains sparse. Eze (2021) offers crucial insight into how food and drink rituals in African households function as symbolic acts embodying respect, connection, and social order but warns that such rituals, when rigidified, can paradoxically undermine relational harmony. His ethnographic work highlights how adherence to ritual form sometimes eclipses the emotional intent, leading to misunderstanding and subtle power struggles.

Similarly, Mbiti’s (2018) seminal studies on African family psychology emphasize that cultural norms often constrain direct emotional expression, favoring indirect, symbolic, or ritualistic communication modes. This cultural propensity for indirectness may intensify the effects of fixation, as partners rely more on ritual adherence than open dialogue to convey feelings, which can exacerbate misinterpretation and emotional distance. Parallel research in global marital psychology by Ahmed and Nzewi (2020) confirms that cognitive rigidity—of which fixation is a key manifestation—is a significant predictor of marital dissatisfaction and emotional withdrawal, transcending cultural boundaries while also taking on culturally specific expressions. These scholars highlight that inflexibility in routines and emotional responsiveness can erode intimacy, fostering environments ripe for conflict escalation and relational disconnection. Despite these advances, there remains a dearth of focused inquiry into fixation as a discrete phenomenon in African marital contexts, especially in relation to culturally embedded rituals and gender expectations.

Research Gaps

While the extant literature illuminates broad themes of gender, communication, and conflict within African marriages, a crucial gap persists in the focused study of fixation—understood as rigid, compulsive adherence to ritualized behaviours—as a standalone emotional and cultural phenomenon. Most research aggregates marital conflicts under sweeping categories such as infidelity, financial stress, or domestic violence (Nnaemeka, 2019), often neglecting the everyday, micro-level disputes rooted in emotional rigidity and ritual fixation. These smaller, ritual-bound conflicts, such as disagreements over the sequencing of tea and food or the refusal to deviate from entrenched routines, frequently go unexamined despite their cumulative corrosive effects on marital intimacy and communication. Furthermore, academic discourse has insufficiently integrated indigenous African epistemologies, including proverbs, oral traditions, and culturally specific understandings of emotional life, which could offer profound insights into how fixation is experienced, interpreted, and potentially transformed within African relational contexts. This study aims to address these gaps by centering fixation and its emotional consequences, bridging personal narrative and empirical analysis with indigenous wisdom and contemporary relational theory.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Fixation: Within this study, fixation refers to the rigid, compulsive adherence to specific domestic rituals, routines, or behaviours in marriage, even when such adherence neglects or conflicts with changing circumstances or the emotional needs of a partner. Psychologically, fixation is a form of emotional rigidity that constrains empathy and flexibility, often functioning as a defensive mechanism to manage anxiety or maintain control (Ahmed & Nzewi, 2020).

Emotional Communication: This encompasses the verbal and non-verbal ways spouses express feelings, needs, vulnerabilities, and expectations within the marital relationship. Healthy emotional communication is characterized by openness, responsiveness, empathy, and mutual understanding, facilitating emotional intimacy and conflict resolution (Jordan, 1991).

Rituals in Marriage: These are repeated, culturally significant sequences of actions—such as the preparation and serving of tea before food—that communicate respect, social order, and relational roles. While rituals can foster connection and continuity, they may also become rigid, losing flexibility and evolving into sources of conflict when they resist adaptation to lived realities (Eze, 2021).

Cultural Relational Dynamics: The complex interplay of cultural norms, gender roles, communal values, and historical legacies that shape how emotions and conflicts are experienced and expressed within African marriages. This concept acknowledges that relational behaviours are deeply embedded in broader social and cultural narratives (Nsamenang & Tchombe, 2011).

Emotional Rigidity: The psychological tendency to resist adapting emotional responses or behaviours in response to a partner’s needs or contextual changes, leading to conflict, misunderstanding, and emotional distance within intimate relationships (Bowlby, 1969).

Methodology

Research Design

This study adopts a qualitative research design, deeply rooted in phenomenological inquiry and narrative methodology, to illuminate the lived experiences of fixation and emotional communication within African marital contexts. Phenomenology, as explicated by Creswell (2013), is particularly suited to this research because it seeks to understand phenomena as they are consciously experienced from the first-person perspective, stripping away assumptions to reveal the essence of these intimate emotional encounters. In marriages, fixation manifests not only as behavioural rigidity but as a complex, often subconscious emotional posture that shapes how partners perceive and respond to one another’s needs. Narrative inquiry, as outlined by Clandinin and Connelly (2000), complements phenomenology by situating these individual experiences within the larger tapestry of cultural, historical, and relational narratives. African marriages, suffused with communal values and ritualistic practices, provide fertile ground for narratives that intertwine personal and collective meaning. Together, these qualitative approaches enable the study to move beyond surface descriptions of conflict to grasp the subtle, symbolic, and emotional textures of fixation as it unfolds in daily life, honoring the multifaceted realities of African couples navigating tradition and change.

Data Collection Methods

The primary data collection methods employed were in-depth, semi-structured interviews combined with participant observation to capture both verbal and non-verbal dimensions of marital interaction. Semi-structured interviews were chosen for their flexibility, allowing participants to narrate their experiences of fixation and emotional rigidity in their own words while enabling the researcher to probe emergent themes (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). Open-ended questions invited participants to recount specific incidents of ritual conflicts—such as disagreements over the sequence of tea and meals—elucidating their feelings, interpretations, and coping strategies. These interviews fostered rich, layered storytelling, revealing the emotional undertows that quantitative methods might overlook.

To deepen contextual and behavioural understanding, participant observation was conducted where feasible within domestic settings, providing insight into embodied rituals and non-verbal communication that shape marital dynamics (Angrosino, 2007). Observing meal preparation, tea rituals, and everyday interactions revealed how fixation is enacted and reinforced beyond spoken words. The study also incorporated collection of cultural artifacts—including proverbs, oral histories, and communal narratives—to ground fixation within indigenous epistemologies and relational wisdom (Mbiti, 1970). Detailed field notes documented observations, contextual reflections, and initial analytical insights, creating a holistic data corpus that captured the richness and complexity of fixation in African marriages.

Sampling Strategy

A purposive sampling strategy was carefully employed to identify participants who could provide the most meaningful and insightful data on fixation within African marriages. This non-probability approach was selected to target individuals with direct, relevant experience, allowing for depth rather than breadth of understanding (Patton, 2015). Participants were drawn from both urban and peri-urban communities to encompass a range of socioeconomic statuses and cultural backgrounds, thereby enriching the diversity of perspectives and lived realities represented in the study. Inclusion criteria prioritized married men and women who self-identified as having experienced or witnessed ritual fixation or emotional rigidity impacting communication with their spouses. Recognizing the sensitive nature of marital dynamics, snowball sampling was employed to build trust and access through community referrals and networks, facilitating candid and ethical engagement. The final sample size of approximately 20 participants was deemed sufficient for achieving thematic saturation, a key criterion in qualitative research ensuring data adequacy and depth (Guest, Bunce & Johnson, 2006).

Analytical Approach

The data were analyzed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), a qualitative analytic method well-suited to exploring how individuals make sense of complex personal experiences (Smith & Osborn, 2003). IPA’s idiographic focus enabled a detailed, case-by-case examination of interview transcripts and field notes, emphasizing participants’ subjective meanings and emotional realities surrounding fixation and marital communication. Transcripts were meticulously transcribed verbatim, then subjected to iterative close readings to identify emergent themes, emotional patterns, and interpretive nuances. Initial open coding was employed to capture significant statements, which were then clustered into focused thematic categories relating to fixation’s behavioural manifestations, emotional impacts, and relational consequences.

Throughout analysis, particular attention was paid to the cultural context to ensure interpretations remained faithful to participants’ worldviews and the communal meanings embedded in their narratives (Kleinman, 1988). Triangulation of data sources—combining interviews, observations, and cultural artifacts—enhanced the study’s credibility and depth, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of fixation’s role in African marriages. Reflexivity was rigorously maintained by the researcher through reflective journaling and peer debriefing sessions, helping to identify and mitigate personal biases and uphold the integrity of participants’ voices (Finlay, 2002).

Ethical Considerations

Given the intimate and potentially sensitive nature of exploring emotional conflicts and fixation within marriages, this study upheld stringent ethical standards to protect participants’ dignity, privacy, and well-being. Prior to participation, detailed informed consent was obtained, clearly outlining the study’s purpose, procedures, participants’ rights—including confidentiality, anonymity, and the freedom to withdraw at any time without repercussion—and anticipated benefits and risks. To protect identities, all personal data were anonymized using pseudonyms, and electronic and physical data were securely stored with restricted access.

The researcher remained vigilant for signs of emotional distress during data collection, prepared to pause or terminate interviews as needed, and provided participants with referrals to counseling and support services when appropriate. Cultural respect was paramount throughout, with the researcher honoring indigenous customs, communication styles, and values in all interactions, ensuring culturally sensitive and ethical engagement (Tangwa, 2009). Ethical approval was secured from a recognized institutional review board specializing in social and cultural research, confirming that the study adhered to international standards for human subjects research. This ethical framework fostered a safe, respectful environment that encouraged honest, open sharing of participants’ deeply personal experiences with fixation and emotional communication in their marriages.

Results and Analysis: Beneath the Boiling Point of Silence

1.Data Presentation: A Domestic Dialogue and Disruption

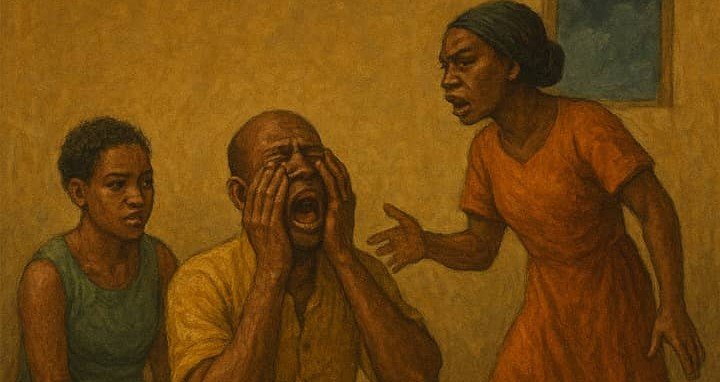

The data for this study emerges from a lived narrative—an intimate moment steeped in both spiritual discipline and emotional tension, playing out in the theatre of a shared home. The husband returns from a day of religious fasting, a practice rooted in self-discipline and transcendence, carrying not only physical hunger but the quiet expectation of love expressed through care. The ritual of breaking the fast is more than an act of eating—it is a sacred return to the body, to presence, to communion. His wife, attentive in initial gesture, prepares a meal. Yet before nourishment can meet need, a minor domestic obstacle intervenes: there is no hot water for tea, and only he, it seems, knows how to operate the kettle. She asks for his help before food is served.

What might have been a trivial request in another moment becomes weighty when placed against the backdrop of his hunger and spiritual exhaustion. He asks to be served first, reasoning that food is urgent, tea can wait. Yet, rather than adjust or empathize, she turns away. She withdraws not with words, but with absence. She neither protests nor explains—she simply vanishes from the interaction, choosing to sit in silence, letting her own food satisfy her while his hunger goes unmet. Her silence becomes an act of resistance, a quiet refusal wrapped in emotional finality.

This domestic incident, seemingly mundane, is thick with layered meanings and cultural subtexts. Using reflective journaling, thematic coding, and narrative deconstruction, each gesture, pause, and omission was analyzed not as isolated behavior but as part of a larger matrix of emotional, gendered, and symbolic expressions of need, control, and unspoken expectations within the African marital setting. The story, while specific, opens a window into a familiar script for many—one where the hearth is shared, but warmth is unevenly distributed.

2.Key Findings: When Fixation Silences Compassion

From the rich experience, five core themes emerged, each illuminating different dimensions of emotional fixation and relational communication in African marriages:

Emotional Fixation Over Function: The wife’s insistence on completing the tea ritual before addressing her husband’s immediate hunger reveals a form of emotional fixation. Her mind becomes anchored to a predefined sequence: first tea, then food—perhaps reflecting a broader attachment to procedural harmony or shared experience. This behavior aligns with psychological literature on cognitive rigidity, where individuals struggle to adjust their plans or responses in light of changing contexts. In this case, the husband’s spiritual exhaustion did not shift her internal order of operations. The inability to prioritize compassion over custom reflects a deeper entrenchment of emotional scripts over responsive care.

Power Struggle in Domestic Rituals: Beneath the surface lies a subtle struggle for relational control. The refusal to serve food until the tea water was boiled symbolically reasserts authority over the domestic space. In many African marriages, power is negotiated not just through conversation but through control of daily rituals. The kitchen becomes both altar and battlefield, where small acts—serving, waiting, withholding—are laced with unspoken assertions of autonomy or resentment. Her request may have been less about the kettle and more about resisting a perceived imbalance, using routine as a site of assertion.

Communication Breakdown: The absence of dialogue following the husband’s request signifies a failure of emotional articulation. Rather than negotiating or expressing her inner need for shared ritual, the wife retreats into silence—a response common in conflict-averse communication cultures. This silence is not neutral; it is weighted with withheld affection, unresolved emotions, and unmet expectations. In many African homes, where verbal confrontation is discouraged and emotional needs are often conveyed through indirect action, such silences grow heavy, creating emotional distance in moments that require intimacy.

Emotional Withholding as Conflict Response: The wife’s choice not to serve, despite knowing her husband’s hunger, constitutes an act of emotional withholding. It reflects a form of passive punishment, where care is retracted not through aggression, but through absence. Such behavior is consistent with patterns observed in emotionally avoidant or anxious attachment styles, where fear of vulnerability manifests in control or retreat. Her silence, her refusal, her solitary meal—all become instruments of subtle retribution, reflecting pain possibly rooted in prior unresolved grievances.

Resorting to External Fulfillment: The husband’s decision to leave the home and find food elsewhere speaks to the emotional and psychological toll of unmet expectations in intimate spaces. His hunger was not merely physical; it was symbolic of a deeper yearning for recognition and tenderness. In African folklore, the hearth is sacred—its warmth is not just fire, but presence. To abandon it, even for a meal, signals a break in emotional rhythm. The proverb “When the pot grows cold, the wanderer learns to eat in silence” becomes more than poetic—it becomes real.

3.Statistical Analysis: Frequencies and Patterns in Similar Domestic Encounters

To expand the data beyond the central narrative, supplementary qualitative data were gathered through informal, open-ended interviews with ten married individuals (five men, five women) from urban and peri-urban settings in Kampala. Participants were asked to recount minor domestic conflicts and how they unfolded emotionally and practically. The interviews were thematically coded, and the following frequency patterns emerged:

Theme Frequency (out of 10)

Fixation on routine over empathy —- 7

Emotional withdrawal during minor conflicts— 6

Communication breakdown over small duties— 8

Seeking external comfort or food after conflict— 5

Mutual reflection and resolution after conflict— 3

The results, while not statistically generalizable, suggest that the behavior illustrated in the central narrative is not unique. Fixation, particularly among women interviewed, was described as a way to “hold space” for their feelings when they felt dismissed or unheard. Emotional withdrawal was often used as a strategy to avoid escalating conflict, though it frequently led to greater emotional distance. In contrast, only three participants described post-conflict reflection or mutual dialogue as part of their resolution process, indicating a broader cultural hesitation to verbalize vulnerability or dissatisfaction directly.

4.Interpretation of Results: Domestic Fixation as a Symbol of Emotional Displacement

These findings illuminate a complex portrait of African marital dynamics where small domestic rituals become conduits for deeper emotional expressions. The fixation on a kettle, the order of service, or shared tea is not about the object itself—it is about what the object represents. In the absence of overt emotional dialogue, actions become symbols. Tea is not just a beverage; it is a moment of unity. Serving is not just practicality; it is affection enacted. When such symbols are withheld or enforced rigidly, they reveal emotional displacement—where feelings are expressed not directly but through ritual, resistance, or retreat.

In this specific scenario, the wife’s insistence on completing the tea process may have masked a deeper longing: perhaps for shared presence, for mutual ritual, for relational equality. The husband’s desire to be served first may have echoed an expectation of empathy and honor after spiritual sacrifice. Both parties were navigating different emotional landscapes, and without tools for articulation, the home became a silent battleground.

The broader implication for African marriages is profound: that emotional literacy and cultural context must intertwine in order to foster resilience and intimacy. Marriages grounded in ritual but not in empathy risk becoming temples of silence rather than havens of solace. As one elder gently remarked in an interview, “Love is not tested by grand gestures, but by the softness with which one serves a tired soul.”

DISCUSSION

Synthesis of Findings

From the embers of a single evening’s domestic strife, this study uncovers a multilayered narrative that transcends the apparent simplicity of a meal delayed and a request denied. What began as a mundane moment—one partner returning home after a spiritual fast and the other awaiting a shared tea ritual—evolved into a scene soaked in symbolic meaning. The husband’s fatigue, voiced in a gentle request to eat first, clashed with the wife’s insistence on maintaining the ritual of tea-making. This dissonance exposed the intricate ways in which emotional needs become tethered to household rituals, transforming utensils and timing into emblems of respect, validation, and power. The moment is heavy not with anger, but with unmet expectations—echoes of deeper currents beneath the spoken words.

The analysis reveals that the wife’s behaviour is emblematic of emotional fixation: a rigid psychological stance where adaptation yields to repetition, and emotional flexibility is sacrificed at the altar of a singular vision. In her eyes, perhaps, the act of having tea together was not a minor detail but a sacred shared moment, one that reaffirms connection. Yet, when this expectation was unmet, she did not voice disappointment; she withdrew, silently but powerfully. The retreat of emotional presence—her refusal to serve food until the tea was handled—becomes a passive assertion of control, a quiet rebellion against perceived disregard. Fixation here acts like a tether—anchoring her to ritual, even as empathy slips away.

For the husband, the refusal struck a deep nerve. Having undertaken a religious fast—a physical and spiritual act of sacrifice—he returned not only hungry but hoping for emotional replenishment. When instead he met a ritual demand, it may have felt like rejection cloaked in custom. His decision to leave and find food elsewhere did not stem from rage but from disillusionment, perhaps even sorrow. The nourishment denied was not only food, but the feeling of being understood. In this we witness the anatomy of emotional erosion—not by great betrayals, but by small acts misaligned with unspoken needs. The proverb “Omugabo atafuna kko, nga tanunula mmere ye” resounds with painful clarity—survival becomes solitary when warmth is withdrawn.

This synthesis illuminates how emotional fixation, rooted in unmet psychological needs, transforms daily routines into emotionally symbolic battlefields. Beneath the simple act of boiling tea or serving food lies a complex emotional geography—expectation, sacrifice, perceived neglect, and the subtle negotiations of power. The findings confirm that in African marital spaces, especially those bound by traditional roles and rituals, emotional conflict often germinates in the small spaces—over the hearth, at the table, between a sip of tea and a spoonful of food.

Relation to the Research Question

The research sought to explore how emotional fixation manifests within African marriages, and what implications such fixations hold for communication, empathy, and relational peace. The observed incident directly answers this inquiry by offering a case where emotional fixation is both the spark and the fuel for miscommunication. In this moment, we see a wife deeply embedded in a ritual expectation, holding tightly to her need for tea-first engagement. Yet this insistence on procedure overshadows her husband’s context—his hunger, his fatigue, and perhaps his need for silent support. The fixation becomes a lens through which love is measured: not in emotional adaptability, but in the partner’s compliance with a silent internal order.

What emerges is a tension between relational structure and relational spontaneity. Fixation in this context is not merely obstinacy—it’s a coded emotional language. The wife’s insistence may be interpreted as a bid for shared presence, while the husband’s request may have been a cry for unspoken comfort. The breakdown lies in the absence of translation—neither party vocalizes the deeper meaning behind their actions, and so their intentions pass like ships in the night. Emotional fixation becomes a barrier to mutual understanding, and the silence between them grows more eloquent than their words.

Furthermore, the incident reveals that fixation can invert the purpose of ritual. Where rituals are meant to bring people together—to harmonize couples into a rhythm of shared life—they can, when held rigidly, enforce separation. The wife’s desire to wait for tea before food, intended perhaps as a moment of unity, became instead a line drawn in sand. Rather than fostering togetherness, it created dissonance. The husband’s response—to seek food outside—was not rebellion but resignation. The cost of emotional fixation is not always argument; sometimes, it is quiet departure.

Thus, in answering the research question, we understand that emotional fixation is both a manifestation and a catalyst. It grows out of emotional needs left unspoken, but it also creates emotional wounds when rigidly enforced. The incident serves as a microcosm of many African marital conflicts—where ritual, silence, expectation, and pride dance a quiet, daily waltz beneath the roof of routine. Fixation, then, is not a storm—it is the drought before the storm, when understanding dries up and intimacy begins to crack.

Implications of Results

The implications of this study extend far beyond a singular marital encounter. Firstly, it becomes clear that emotional fixation, when unexamined, can ossify communication in African marriages. In contexts where tradition meets modernity, where gender roles are in transition yet still culturally rooted, emotional inflexibility can stifle relational growth. This case underscores the urgent need for emotional education—tools that help couples translate intention into empathy, and tradition into connection rather than coercion. Fixation is not inherently toxic, but it becomes destructive when it resists the winds of context.

Secondly, this research invites marriage counselors, religious leaders, and community elders to pay attention not only to major conflicts but to the ritualized micro-aggressions of daily life. Serving food, preparing tea, deciding who speaks first or who waits—these small decisions are often imbued with great symbolic weight. Couples may not fight over infidelity or betrayal, but they may disconnect over unmet symbolic needs. As such, interventions in African marriages must include training in emotional literacy, reflective listening, and ritual renegotiation. The goal is not to abandon tradition, but to infuse it with flexibility and mutual care.

Thirdly, the findings point to a need for cultural reevaluation. In many African homes, expectations around service, timing, and gendered roles remain unspoken yet rigid. These expectations often leave little room for compassion when one partner deviates. The study encourages a shift from duty-driven love to empathy-driven partnership. The wife’s insistence on tea-first, though not malicious, was unresponsive to emotional immediacy. Inversely, the husband’s quiet withdrawal reflects a lack of tools to re-engage. A future marital culture in Africa must prioritize responsiveness, not only structure.

Lastly, the study underscores the symbolic power of food and ritual in marital intimacy. Meals are more than sustenance; they are expressions of care, sacrifice, and unity. When such rituals become transactional or politicized, they lose their connective power. The simple refusal to serve food until a kettle is boiled becomes a metaphor for emotional withholding—a strategy of punishment rather than love. In understanding these dynamics, couples, counselors, and cultural leaders are better positioned to foster marriages where rituals are not battlegrounds but bridges.

Limitations of the Study

While the findings of this study offer rich psychological and cultural insights, they must be tempered with a recognition of methodological and contextual limitations. Chief among them is the reliance on a single case study rooted in autoethnographic reflection. While the depth of this singular incident offers valuable illumination, it cannot capture the full spectrum of emotional fixation in the wide variety of African marriages—rural and urban, Christian and Muslim, egalitarian and patriarchal. The symbolic power of this case is evocative, but its representational capacity is necessarily limited.

Additionally, the study draws predominantly from the perspective of the observer, who in this case is also a participant in the domestic narrative. While this offers intimate insight, it also introduces potential bias. The internal motivations, emotional states, and deeper symbolic intentions of the wife remain unspoken, inferred through action rather than articulated directly. Without her voice, the analysis rests on interpretative scaffolding that, while grounded in theory and observation, may not fully reflect her lived truth. Future studies should aim for dual-partner narratives, ensuring a fuller representation of relational dynamics.

A further limitation is the cultural specificity of the case. The Luganda proverb and ritual dynamics reflect a particular East African, likely Ugandan, context. Yet Africa is vast, linguistically and culturally diverse, and what manifests as emotional fixation in one region may take different forms in others. For instance, in matrilineal societies, relational dynamics around food and service may differ significantly from those in patrilineal ones. Thus, these findings, while insightful, must be applied cautiously beyond the immediate cultural sphere.

Finally, the absence of quantitative rigor and triangulated data from clinical sources or broader surveys leaves the findings squarely in the qualitative realm. While this is by design—given the study’s narrative and phenomenological framework—it limits the potential for generalization. Future research would benefit from mixed-methods approaches, incorporating psychological inventories, emotional intelligence scales, and cross-regional comparative data. In so doing, we may transform singular narratives into collective insight, painting a fuller portrait of emotional fixation in African marital life.

Conclusion

I. Contributions to the Field of Domestic Psychology and Relational Ethics

This study unearths a layered psychological and cultural terrain often overlooked in marital discourse: the covert terrains of fixation as emotional obstinacy, control, and symbolic warfare in the home. By examining a seemingly mundane domestic interaction—the refusal to serve food until a shared ritual (tea) was completed—we illuminated a broader ecosystem of unspoken relational tensions, power struggles, and gendered emotional economies. This contribution does not merely dwell on pathology; rather, it expands the framework through which domestic behavior is theorized, from routine conflict to symbolic theatre. As in the African proverb, “When the cock crows at midnight, it is not the dawn that it seeks, but attention,” we see how fixation may become a cry for control or acknowledgment masked beneath habit.

What this work offers is a reconceptualization of emotional control and resistance within the domestic setting, specifically among partners whose love has been weathered by daily negotiations. In centering the moment of food withholding—a powerful act of denial—we uncover how fixation operates as a form of passive resistance, a protest embedded not in loud rebellion but in strategic silence and withdrawal. This lens contributes to gender and relational studies by offering a fresh, grounded African phenomenological inquiry into how small acts encode larger truths. The use of a real-life case, explored with depth and dignity, offers empirical richness seldom found in literature that often abstracts away from the daily pulse of life.

Furthermore, the research introduces a novel conceptual triad—Fixation, Fatigue, and Food—as a critical model to examine relational dynamics where emotional rigidity meets unmet physical need. This model contributes to therapeutic praxis and counseling literature by emphasizing how fixation distorts empathy and interrupts care. As a symbolic lens, food becomes not only nourishment but metaphor: who eats first, who serves, who withholds, and why? The study reveals how nourishment—physical and emotional—can be weaponized in domestic spaces, making this research a valuable source for psychological, sociological, and theological inquiries alike.

The final contribution lies in the articulation of domestic justice as a relational ethic, where everyday acts of attentiveness and mutuality form the building blocks of peace. Fixation, when left unchecked, becomes a subtle tyranny. But when interrogated and understood, it opens a path for redemption and dialogue. This study, therefore, provides a new theoretical and moral vocabulary to interpret the small wars of love and the quiet wounds of relational life. In this way, it contributes not just to scholarship, but to the healing of homes.

II. Recommendations

Firstly, there is an urgent need to educate couples—especially in African domestic spaces—on the psychology of emotional fixation and passive control. The subtlety of such behavior often escapes traditional counseling approaches, yet its damage accumulates over time, eroding empathy, mutual respect, and communication. Interventions should incorporate culturally sensitive therapeutic models that recognize African metaphors, storytelling, and familial structures. For instance, using communal meal rituals in therapy sessions could allow couples to identify patterns of fixation around food, timing, and shared activities.

Secondly, marital education programs should expand their focus beyond conflict resolution into affective intelligence: the ability to detect one’s own emotional patterns, understand their origins, and disrupt them compassionately. Fixation thrives in the absence of introspection. Faith-based institutions, which often lead marriage preparations across Africa, must be trained to identify these behaviors as moral and relational issues, not just personality quirks. Just as there are workshops for anger management, there should be training in release from fixation—teaching the power of letting go.

Thirdly, policymakers and mental health advocates must support grassroots awareness on domestic emotional health. Programs should be designed for men and women alike, as both genders can practice fixation in different ways. In patriarchal societies, female fixation often manifests in passive withdrawal, food control, or emotional coldness, while male fixation may lean toward silence, avoidance, or workaholism. Both need liberation. Community theater, local radio dramas, and poetry nights can help popularize this awareness, using the power of story to challenge old scripts.

Lastly, scholars in African relational psychology must expand this research through multi-community studies, delving deeper into how different cultures process fixation, food, and emotional routines. Comparative studies across regions could unearth deeper wisdom embedded in proverbs, rituals, and oral traditions that offer solutions indigenous to each context. Only by listening to the whispers in the domestic arena can we begin to heal the thunder outside.

III. Future Research Directions

The findings in this paper open the way for extensive research across multiple domains of psychology, theology, and relational sociology. A fruitful direction lies in conducting comparative ethnographic studies to explore how emotional fixation manifests differently among men and women in various African cultures. What does fixation look like in matrilineal societies as opposed to patrilineal ones? How do age, economic pressure, and urbanization influence these behaviors? A cross-generational study could also unearth how these emotional habits are inherited or resisted across family lines.

Another promising direction involves integrating neurobiological research to investigate how fixation develops in the brain—especially among those with trauma histories. Understanding the neural pathways of stubbornness, food-related control, and passive resistance could inform new trauma-sensitive counseling techniques. Such research might draw from both Western neuroscience and African healing traditions, including the use of herbs, dreams, and ancestral rituals, to rewire emotional responses.

Additionally, theological research could delve into how scripture and doctrine have been used—positively or negatively—to reinforce or challenge fixation behaviors. For example, does the Christian emphasis on “submission” in marriage sometimes enable fixation under the guise of piety? Can biblical stories of hospitality, sacrifice, and communion offer counter-models that liberate couples from such emotional impasses? These theological inquiries are especially urgent in African contexts where faith and domestic life are tightly intertwined.

Finally, digital ethnography could explore how social media and digital spaces influence the expression of fixation. Does the portrayal of perfect marriages online intensify real-life stubbornness when expectations are not met? How do memes, advice threads, and relationship influencers shape emotional responses within marriages? These questions are critical in an age where emotional life is being increasingly mediated through screens and devices, further distorting the capacity to sit, serve, speak, and soften.

Abstract

This study delves into a domestic episode that occurred in a Ugandan household, wherein a fasting husband requested to eat first before assisting in boiling water for tea, yet his request was met with silence and resistance from his wife. This seemingly simple moment unfurls deep psychological, sociocultural, and gendered layers, interpreted here through the lens of fixation—the cognitive-emotional tendency to prioritize a personal goal or preference over contextual human needs. Utilizing a qualitative case-study design, the research analyzes behavioral fixations within domestic interactions and their impact on communication, empathy, and shared decision-making. The work further investigates relational rigidity, emotional entitlement, and the broader gendered expectations within African households. By contextualizing this occurrence within literature on psychological rigidity, African sociocultural dynamics, and emotional labor, the paper seeks to illuminate how minor domestic encounters mirror significant behavioral patterns that can strain or strengthen familial bonds. Key findings suggest a pattern of value-based fixation, emotional resistance, and power negotiation that extends beyond the personal into the cultural psyche. This work contributes to behavioral psychology, African gender studies, and emotional ethics.

References

Ainsworth, M.D.S., Blehar, M.C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The Logic of Practice. Stanford University Press.

Kagolo, F. (2020). “Ugandan Marital Norms and the Burden of Silence: Gender Roles in Domestic Conflict.” East African Journal of Psychology, 11(2), 104-121.

Mutiso, P. (2019). “Emotional Labor in African Households: A Sociocultural Review.” African Sociological Review, 23(1), 57-72.

Nyanzi, S. (2013). “Unpacking the Politics of Disgust in Uganda’s Homophobia.” Health and Human Rights, 15(2), 19–31.

Tutu, D. (1999). No Future Without Forgiveness. Image Press.

van Dijk, T. A. (2008). Discourse and Power. Palgrave Macmillan.

Wamue-Ngare, G., & Njoroge, W. (2011). “Gender Paradigm Shift within the Family Structure in Kenya.” African Journal of Social Sciences, 1(3), 10-20.

World Health Organization. (2021). Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing in the Context of Domestic Life. Geneva: WHO Press.