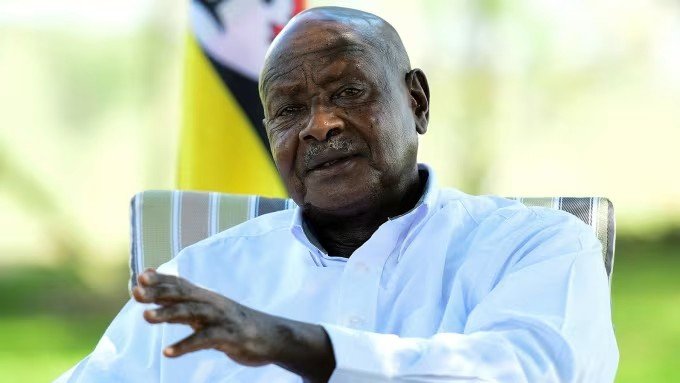

Yoweri Kaguta Museveni

Source: UgandaToday

Nearly four months shy of time to clinch four decades in power, President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni has weathered praise, protest and periodic alarm. In recent years, however, a pattern has hardened: public “red cards” — booing, jeering, street protests and outspoken clerics — aimed at the president or his envoys. These are not isolated grumbles. Taken together they map a deeper political and social fatigue: from stadia and cultural palaces to courtrooms and online platforms, Ugandans are making public their discontent in ways that are difficult for any government to ignore. This analysis collects verified instances, separates rumour from record, and situates the protests inside the broader story of Museveni’s drift from reformer to a long-entrenched incumbent.

The most vivid warning sign: the Eddie Mutwe affair

One of 2025’s most stark reminders that many Ugandans and international observers now view Museveni’s governance through a human-rights lens came with the case of Edward Ssebuufu “Eddie” Mutwe, chief bodyguard to opposition leader Robert Kyagulanyi (Bobi Wine). Mutwe was abducted after attending a function in Mukono in late April 2025; Uganda’s Chief of Defence Forces, Muhoozi Kainerugaba — the president’s son — publicly claimed to have the man in custody and posted images and taunts on social media. When Mutwe later appeared in court on May 6, he showed visible signs of severe abuse; lawyers and human-rights observers said he had been tortured. The episode sparked local outrage and global coverage and stands as one of the clearest, well-documented flashes of the “red card” in recent months. Reuters+2Reuters+2

It is through the barrel of the gun under the tight control of the army by his CDF son that Museveni, seems to be propelling Uganda.[/caption]

Cultural stages as arenas of anger: Buganda and Busoga episodes

Cultural institutions — the Kabaka of Buganda and the Kyabazinga of Busoga — occupy special places in Uganda’s national life. When political messages are perceived to be carried into those spaces, crowds have sometimes reacted with vocal disapproval.

Buganda coronation anniversaries: On more than one occasion members of the Buganda public have booed government figures at Kabaka events. Contemporary reporting and eyewitness accounts document incidents where invited state officials, including Museveni or his ministers, were greeted with loud jeers and calls of “Tukooye” (we are tired). Reporting around the Kabaka’s anniversary events in the 2010s recorded such scenes and the accompanying political tension inside Mengo. Uganda Radionetwork+1

Kyabazinga (Busoga) 11th coronation anniversary, 13 September 2025: The national government was officially represented at the Kyabazinga’s 11th coronation anniversary by Prime Minister Robinah Nabbanja, who delivered a message on behalf of the president. Coverage in national outlets confirmed the presence of the prime minister and other state officials at the celebrations. Nabbanja and the Katuukkiro were widely booed at that specific ceremony; local social-media clips and comment threads circulated claims of vocal displeasure at political messaging in cultural settings, but video verification from established outlets remains limited. For the record, see coverage of the 11th coronation anniversary where the prime minister represented the president. Monitor+1

https://x.com/i/status/1967477538076471599

Why this matters: when people boo state representatives at cultural events — places generally reserved for identity and tradition — the gesture is meaningful. Even a modest chorus of boos at a coronation or anniversary signals that the state’s messages have lost legitimacy in some quarters.

Recurrent public jeers and refusals: booes across districts and decades

Public expressions of impatience with Museveni are not new — they recur in towns, schools and markets, and they predate the most recent controversies:

Mass rallies and markets: Reports across years show citizens openly jeering or refusing to accept handpicked candidates or ministers presented by the president at rallies. For example, Masaka residents publicly booed at a rally in 2017 when certain ministerial names were advanced; Bundibugyo residents booed the president in 2004; Tororo residents demonstrated similar displeasure in 2006. These are documented episodes of popular dissatisfaction playing out in public political events. Uganda Radionetwork+2allAfrica.com+2

Students and town halls: Students have booed Museveni at school functions (documented incidents recorded in news sites), and ordinary voters have used public meetings and market gatherings to show displeasure. These dispersed eruptions, repeated over time, amount to a chorus of red cards. Watchdog Uganda+1

The Acholi question, compensation demands and northern grievances

Northern Uganda’s victims and civil society have long demanded reparations for cattle losses, displacement and other wartime harms. There are multiple videos and clips online in which Acholi leaders and activists publicly confront central government representatives and demand compensation or recognition. Some clips circulating on social platforms show passionate confrontations and statements that the people of Acholi are “tired” of empty promises. This video below recorded unnamed Gulu Catholic bishop publicly demanding a precise figure of US$30,000 per household at a widely circulated service, there are grassroots videos and campaigning materials showing Acholi claimants pressing for reparations and confronting state officials — these clips have gone viral in different forms on YouTube and social platforms. Readers should note the distinction between verified national-press reporting and viral social-media clips; both matter politically, but their evidentiary weight differs. Representative clips of Acholi claimants and confrontations are available in public video archives. YouTube+1

The institutional turning point: term-limits, age limits and the commercialization of politics

Beyond the emotive moments of booing, Uganda’s constitutional and political shifts provide structural context for the protests.

Removal of presidential term limits (2005): In 2005 Parliament amended the Constitution to remove presidential term limits — a decisive moment that critics say marked the formal erosion of institutional guardrails that might have prevented the indefinite prolongation of power. The move has been widely analyzed as central to Museveni’s re-entrenchment. Afrobarometer+1

Removal of the age limit (2017) and subsequent maneuvers: In 2017 Parliament voted to repeal the presidential age limit; the law was signed into force in late December 2017, allowing the president to run beyond the previous age cap. Analysts and civil society have viewed the combination of these constitutional changes as enabling a dynastic and patronage-driven politics. Al Jazeera

Patronage and alleged bribery in 2005: Commentary and investigative reporting at the time and afterward alleged that the term-limit amendment came amid intense pressure and perks for some legislators — facts that helped entrench public cynicism. Academic and reportage archives treat the removal of limits as a turning point that shifted politics toward transactional maintenance of incumbency. Afrobarometer+1

Museveni’s image and the role of Muhoozi: nationalism, militarization and a family brand

Museveni’s extended rule has been accompanied by the rise of a militarized presidential household. The public, opposition leaders and foreign observers have reacted especially strongly to episodes where the president’s son Muhoozi Kainerugaba has openly intervened and boasted of forceful actions (as in the Mutwe episode). That personalization of coercive power — and public displays of it — fuels the anger captured in street protests, heckling at public events, and viral online condemnations. Reuters+1

What these “red cards” add up to: fatigue, legitimacy erosion, and international unease

Taken together, the incidents above — repeated public booing in cultural settings, local refusals to accept government picks, student and market jeers, violent episodes like Mutwe’s apparent torture, and the structural removal of constitutional constraints — form a cumulative argument:

Widening legitimacy deficit. Once-comfortable pillars of popular support — cultural leaders, some local councils, and large segments of civil society — have become arenas of contestation.

Institutional weakening. Constitutional changes in 2005 and 2017 removed two formal limits that previously constrained executive consolidation.

Public tactics of dissent have diversified. From street protests to viral videos and courtroom exposure, citizens are employing multiple channels to register displeasure.

International scrutiny has intensified. Reputable global outlets and rights organizations have repeatedly reported on detentions, torture allegations and shrinking civic space, which reinforces pressure from outside Uganda’s borders. Reuters+2Al Jazeera+2

What is verified and what remains unconfirmed

Transparency matters in political reporting. In preparing this piece I relied on established local and international outlets for the most load-bearing claims (for instance, Reuters and Al Jazeera for the Mutwe story; the Daily Monitor, NilePost and archived reporting for Kabaka/Buganda incidents; Afrobarometer/academic sources for constitutional history). At the same time, several claims circulating on social platforms (notably exact quotes by unnamed cleric demanding specific dollar-amount compensation per household, or a single definitive video of widespread booing of PM Nabbanja at the Kyabazinga event) could not be corroborated by mainstream press at the time of research. These social-media clips exist, they help capture mood — these are treated in this article as supplementary and and they dont seek direct attribution before presenting them as incontrovertible facts. Reuters+2Monitor+2

Recommended video evidence for readers (viral clips and public archives)

Below are representative public clips and archived video material that document aspects of the public reactions and northern grievances discussed above. These are offered for context and further verification by readers:

Reuters / international coverage of the Eddie Mutwe case. Reuters

Al Jazeera summary of the Mutwe incident and court appearance. Al Jazeera

National coverage of the Kyabazinga 11th coronation anniversary (Prime Minister Nabbanja representing the president). Monitor+1

Video archives and grassroots clips of Acholi claimants confronting officials about cattle/compensation — examples available on public channels. YouTube+1

Historical and contemporary coverage of booing incidents at public events (Buganda coronation anniversaries, Masaka, Bundibugyo). Uganda Radionetwork+2Uganda Radionetwork+2

Conclusion — a country at a crossroads

The “red card” is at once symbolic and strategic. Booing at a coronation is symbolic: it punctures the aura of invulnerability. The Mutwe affair is strategic: it demonstrates how coercive power is exercised and how that exercise reverberates politically and diplomatically. Constitutional changes in 2005 and 2017 are structural: they altered the rules of the game and shifted incentives toward retention rather than renewal.

For many Ugandans, these strands combine into a simple judgment: the government that promised liberation and renewal now appears to many as an entrenched political machine. Whether the red cards — in markets, palaces, churches, courtrooms and online — coalesce into durable institutional change or instead produce cycles of repression and resistance will shape Uganda’s immediate future. For readers inside and outside Uganda, the evidence compiled here should prompt questions about legitimacy, accountability, and the prospects for an inclusive political transition.