Chapter 1

By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Dedication:

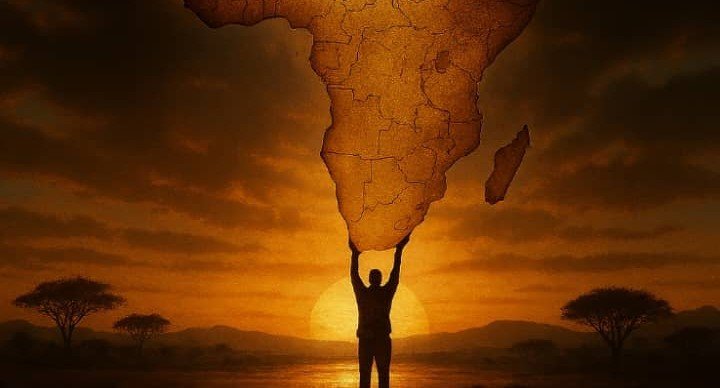

This is lifted up in dedication to the ancestors who watched their lands carved by foreign hands, whose forests, rivers, and mountains were measured with rulers and ink; and to the young Africans who will redraw our destiny, who will chart a path where sovereignty, culture, and memory are inseparable from the lines on the map.

Epigraph:

“The one who draws the path owns the journey.” — Luba proverb, Congo

Preface

Maps are never neutral. They are not merely instruments of navigation, nor are they passive records of geography. They are mirrors of power, codifiers of history, and silent arbiters of destiny. To reclaim the map is to reclaim not only land, but also memory, culture, and sovereignty. It is to challenge centuries of imposed boundaries that have dictated how African peoples move, trade, worship, and organize themselves, often forcing communities into political, economic, and social structures that were alien to their ways of life.

The Berlin Conference of 1884–85, convened in distant European halls far from African soils, is remembered as a diplomatic negotiation, yet in reality it was an orchestrated act of territorial appropriation. The continent, with its rivers, mountains, forests, and thriving trade networks, was carved like a cake for extraction, with little regard for culture, kinship, or sacred sites. The arbitrary lines drawn during that conference continue to haunt Africa today, shaping wars, displacement, and economic dependency. The spiritual cost, often overlooked, lingers in the dislocation of communities and the erasure of indigenous knowledge, leaving generations of Africans navigating a landscape defined by foreign priorities rather than their own histories.

Yet in this challenge lies opportunity. The act of reclaiming the map is profoundly political, cultural, spiritual, and ethical. It is a call for Africans to take the pen, to chart a course that restores justice, protects sacred geography, and reaffirms the bonds between people and land. As the Luba of Congo remind us: “The one who draws the path owns the journey.” Africa must now draw its own path, in law, in spirit, and in memory.

This book that will be written and presented in series of chapters is both an investigation and a vision. It traces the theft of lines, the chains of inherited borders, the greed embedded in maps, and the spiritual truths of our lands. It offers practical, legal, and visionary frameworks for reclaiming Africa’s geography and sovereignty. More than a scholarly exercise, it is a call to awaken the collective consciousness of a continent whose story has too often been told by outsiders. It is an invitation to see the map not as an artifact of power, but as a canvas for justice, for culture, and for the fulfillment of Africa’s destiny.

Chapter 1 — The Theft of Lines

Borders, when we think of them in the abstract, are merely edges, lines drawn to separate one territory from another. Yet in Africa, borders were never just lines; they were instruments of domination, a framework through which entire peoples, economies, and ecologies could be subjugated and redefined according to the ambitions of foreign powers. The very word border, derived from the Old French bordure, seems innocuous, but it conceals a violence embedded in history that has shaped the continent’s political, social, and spiritual life for centuries.

In precolonial Africa, boundaries were not rigid but relational, negotiated over generations through customs, kinship ties, ecological knowledge, and trade networks. Communities moved with the rains, exchanged goods across vast distances, and maintained shared sacred sites in ways that connected people to each other and to the land itself. Forests, rivers, and mountains were living guides, not arbitrary demarcations, and every migration, seasonal move, and trade caravan reflected a deep understanding of geography, ecology, and social reciprocity.

When colonial powers arrived with rulers, compasses, and ink, they imposed a geometry upon a living landscape, converting social and spiritual networks into inert coordinates, and in doing so, they rewrote the rules of human possibility. As the Luba of Congo remind us: “The one who draws the path owns the journey.” In Africa, that path was drawn long before her people could walk it, redirecting the flows of communities, trade, and culture toward the imperatives of extraction, domination, and control.

The Berlin Conference of 1884–85 is often portrayed in textbooks as a polite meeting of diplomats seeking order, but archival records reveal a far more calculated reality: this was an orchestrated partition of human lives and land, an act of systematic dispossession designed to maximize European power. France, Britain, Germany, Belgium, Portugal, and other powers convened thousands of miles away from the territories they claimed, deliberating over maps and territories they had never seen, discussing rivers, mountains, and resource-rich plains as if they were commodities rather than homes, sacred sites, and communities. Lines were drawn with precision, slicing through ethnic groups, trade networks, and cultural zones, utterly indifferent to centuries of negotiation and stewardship that had governed African life. The motivation was not moral, legal, or scholarly; it was economic, geopolitical, and militaristic, with imperial ambitions outweighing the needs and rights of the peoples affected. Mahmood Mamdani’s concept of the “spatial logic of dispossession” captures this reality: space became a tool of domination, and lines on a map were instruments of human subjugation, codifying inequality and entrenching systems of control that persist even today.

Long before colonial powers arrived, Africa’s geography was lived, experienced, and managed through intimate human-ecological relationships. The empires of Mali and Songhai flourished along the Niger River, not merely as political entities, but as hubs of trade, knowledge, and cultural transmission, linking the Sahara, the Sahel, and coastal regions through caravans carrying gold, salt, and manuscripts of mathematics, astronomy, and law. Swahili city-states such as Kilwa, Mombasa, and Zanzibar formed thriving trade networks that connected African producers to Arabia, India, and beyond, creating centers of cosmopolitan culture where languages, religions, and art converged. In Central Africa, forested regions functioned as communal hunting and agricultural spaces, where customary law and spiritual practice governed access and usage across generations. Maps in this context were not instruments of ownership but tools to navigate living relationships; they encoded social contracts, ecological wisdom, and cultural memory. When colonial surveyors imposed grids and straight lines, they did not merely draw boundaries—they severed centuries of interconnected knowledge, substituting abstraction for lived reality, and privileging the logic of extraction over the rhythms of life itself.

The human consequences of these imposed lines are palpable and persistent. Since the wave of independence beginning in 1960, Africa has experienced over seventy major interstate conflicts that can be traced to colonial borders, with the United Nations reporting that nearly forty percent of disputes involve communities whose ethnic, cultural, or linguistic ties were divided by artificial lines. Mali and Burkina Faso continue to dispute regions such as Kossi and Sourou, where populations share long-standing familial, cultural, and economic bonds. Sudan and South Sudan’s prolonged conflicts over oil-rich territories highlight how arbitrary demarcations imposed external control over local livelihoods, exacerbating violence and instability. In northern Nigeria, the Kanuri people were split across administrative regimes, forcing families to navigate multiple legal systems and educational policies while disrupting communal governance structures. Even within Uganda, the Bakonzo of the Rwenzori Mountains find themselves confronting contested land claims and jurisdictional confusion, obstructing both local governance and social cohesion. Such examples illustrate that these lines were not merely geographic—they were instruments of human dislocation, of fractured economies, and of eroded political agency, whose consequences persist in every negotiation, conflict, and census.

Literature and cultural memory preserve and reflect the trauma of these imposed borders. Ngugi wa Thiong’o, in Petals of Blood, portrays communities constrained by alien divisions, highlighting how imposed boundaries prevent collective action and autonomy. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun vividly narrates the human suffering and moral crises precipitated by arbitrary national lines during the Biafran war. Across Africa, oral poetry, songs, and proverbs continue to testify to the rupture of social cohesion: one Shona proverb declares, “A river does not flow in one direction for the sake of a ruler,” reminding us that social and ecological systems resist abstraction and control. Music, literature, and oral tradition preserve memory where maps have erased it, sustaining knowledge of riverine networks, migratory paths, and sacred forests that colonial rulers sought to sever.

Sacred texts across cultures reinforce the ethical and spiritual dimension of land. In Genesis 12:7, God promises Abram the land as a covenant, emphasizing stewardship rather than domination. In the Quran, Surah Al-A’raf (7:74) underscores the responsibility inherent in occupying and tending to the land. Indigenous African cosmologies similarly regard the earth as animate, sacred, and inseparable from communal life and ancestral memory. To impose borders without regard for these spiritual realities was not merely a political act—it was a moral violation, a severing of the sacred relationship between humans and their environment, between the present and the ancestral past. In these frameworks, the theft of lines becomes not only a question of law or politics but a question of justice, ethics, and spiritual integrity.

Research substantiates the systematic nature of this dispossession. Political geographers have shown that colonial maps encoded hierarchies of control, privileging imperial capitals while fragmenting local governance. Anthropologists document the disruption of migratory and trade networks critical for community resilience and ecological stewardship. Economists have demonstrated that arbitrarily imposed borders restricted markets, inhibited regional cooperation, and entrenched economic dependency. These findings confirm that colonial cartography was not a neutral technical exercise but a multidimensional intervention with political, economic, cultural, and social consequences, shaping the very possibility of African sovereignty and self-determination.

Some defend the imposition of fixed borders, arguing that they were necessary for the emergence of modern states, administrative order, and international recognition. Yet historical and contemporary evidence suggests that such boundaries often intensified conflict, obstructed cultural continuity, and undermined legitimacy. Sovereignty is more than the capacity to enforce lines; it is the recognition of history, ecology, culture, and community knowledge. To privilege the interests of a foreign few over those of the many is to deny both practical and ethical sovereignty.

From an interdisciplinary perspective, the theft of Africa’s lines resonates across law, philosophy, theology, history, culture, political science, economics, and even mathematics. Legally, colonial borders ignored centuries-old systems of land tenure and customary authority. Philosophically, they substituted a Western abstraction for relational and ecological understanding. Theologically, they violated covenants and spiritual stewardship. Culturally, they fragmented communities, erasing oral histories and disrupting social memory. Economically, they restricted markets, stifled trade, and entrenched dependency. Mathematically, rigid geometric lines replaced the nuanced contours of rivers, hills, and ecological zones. Across all these lenses, the lesson is the same: when maps are drawn to serve extraction rather than life, injustice becomes inscribed on the land itself.

The African proverb resonates through this history: “If the map doesn’t show the well, the traveler will die of thirst.” Colonial maps ignored the wells of culture, kinship, and spirituality, leaving communities parched even in their own homelands. Reclaiming the map, therefore, is not only a political task but a profound ethical, cultural, and spiritual endeavor. Understanding the theft of lines is the first step toward reclaiming Africa’s ground—its memory, justice, dignity, and sovereignty—and toward drawing a new path where the continent itself holds the pen, its people the compass, and its future the ink.

Bibliography

Adichie, C. N. (2006). Half of a yellow sun. Alfred A. Knopf.

Adichie’s novel offers a poignant narrative of the Nigerian Civil War, illustrating the human cost of arbitrary borders and the fragmentation of communities.

Amin, S. (1972). Underdevelopment and dependence in Black Africa: Historical origins. Journal of Modern African Studies, 10(4), 503–524. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00014296

Amin examines the historical roots of underdevelopment in Africa, linking colonial borders to economic exploitation and dependency.

Anderson, D. M., & Johnson, D. H. (Eds.). (1995). The struggle for land in Southern Africa. James Currey.

This edited volume delves into land disputes in Southern Africa, highlighting how colonial borders have influenced contemporary conflicts.

Baker, C. (2006). Language and identity in Africa. Oxford University Press.

Baker explores the role of language in shaping African identities, emphasizing how colonial borders have affected linguistic communities.

Berman, B., & Lonsdale, J. (1992). Unhappy valley: Conflict in Kenya and Africa. James Currey.

Berman and Lonsdale analyze the historical and political factors leading to conflict in Kenya, with a focus on the impact of colonial borders.

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

Bhabha’s work on postcolonial theory offers insights into how colonial borders have disrupted cultural identities in Africa.

Buchanan, A. (2004). Justice, legitimacy, and self-determination: Moral foundations for international law. Oxford University Press.

Buchanan discusses the moral implications of self-determination and the legitimacy of borders, relevant to African contexts.

Chinua Achebe. (1958). Things fall apart. William Heinemann.

Achebe’s novel provides a narrative of colonial disruption in Igbo society, reflecting the broader impact of imposed borders.

Cohen, R. (2004). Borders and boundaries: Theories and practices of border-making. Rowman & Littlefield.

Cohen examines the theoretical frameworks of border-making, with applications to African colonial experiences.

Dorman, S. R. (2006). The politics of the African frontier: Colonialism and the creation of political boundaries. Cambridge University Press.

Dorman analyzes the political processes behind the creation of African borders during colonialism.

Fanon, F. (1961). The wretched of the earth. Grove Press.

Fanon’s seminal work addresses the psychological and cultural impacts of colonization, including the imposition of borders.

Grosfoguel, R. (2007). The epistemic decolonial turn. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162514

Grosfoguel discusses the need for a decolonial approach to knowledge, challenging the Western-centric understanding of borders.

Hancock, I. (2002). The global impact of African colonial borders. African Studies Review, 45(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/1514933

Hancock explores the global consequences of Africa’s colonial borders, particularly in terms of conflict and identity.

Herbst, J. (2000). States and power in Africa: Comparative lessons in authority and control. Princeton University Press.

Herbst examines how African states have managed authority and control, influenced by colonial border legacies.

Hobsbawm, E. J., & Ranger, T. (Eds.). (1983). The invention of tradition. Cambridge University Press.

This collection explores how traditions, including those related to borders, are constructed and maintained.

Huntington, S. P. (1996). The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order. Simon & Schuster.

Huntington’s theory on cultural conflicts touches upon the role of borders in shaping civilizational identities.

Klein, H. S. (2007). The Atlantic slave trade. Cambridge University Press.

Klein provides historical context on the Atlantic slave trade, which was integral to the establishment of colonial borders.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton University Press.

Mamdani discusses the legacy of colonialism in Africa, including the impact of borders on citizenship and governance.

Mbembe, A. (2001). On the postcolony. University of California Press.

Mbembe offers insights into the postcolonial condition in Africa, with attention to the remnants of colonial borders.

Mbiti, J. S. (1969). African religions and philosophy. Heinemann.

Mbiti’s work provides an understanding of African spiritual beliefs, which are often disrupted by colonial borders.

Miller, D. (2016). Strangers in our midst: The political philosophy of immigration. Harvard University Press.

Miller explores political philosophy related to borders and immigration, with implications for African contexts.

Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-colonialism: The last stage of imperialism. Thomas Nelson & Sons.

Nkrumah critiques the ongoing effects of colonialism, including the artificiality of national borders in Africa.

Nyerere, J. (1968). Ujamaa: Essays on socialism. Oxford University Press.

Nyerere’s essays discuss African socialism and the importance of unity, challenging divisive colonial borders.

Ochieng, W. R. (1995). A history of Kenya. Macmillan.

Ochieng provides a historical account of Kenya, detailing the impact of colonial borders on its development.

Pomeranz, K. (2000). The great divergence: China, Europe, and the making of the modern world economy. Princeton University Press.

Pomeranz compares economic developments, offering insights into how borders have influenced economic disparities.

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Said’s critique of Western perceptions of the East includes discussions on the construction of borders and identities.

Soyinka, W. (1994). The man died: Prison notes of Wole Soyinka. Hill and Wang.

Soyinka’s personal account reflects on the political climate in Nigeria, influenced by colonial legacies.

Thiong’o, N. W. (1977). Petals of blood. Heinemann.

Thiong’o’s novel addresses the social and political issues in postcolonial Kenya, highlighting the effects of borders.

Zeleza, P. T. (2006). The invention of African identities. In The African diaspora: A history through culture (pp. 75–92). Harvard University Press.

Zeleza discusses the construction of African identities, often in response to colonial border impositions.

© 2025 Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

All rights reserved. This work may be shared on social media and messaging platforms for non-commercial purposes, with proper credit to the author. No part of this work may be used for commercial gain without written permission.

Publisher: www.africapublicity.com

Contacts: Emkaijawrites@gmail.com | +256 (0)765871126