By: Isaac Christopher Lubogo

In the charged theatre of Ugandan politics, words are seldom innocent; they are instruments of calibration, persuasion, and sometimes veiled caution. The recent public exchange between Speaker Anita Annet Among and President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni—she expressing gratitude for Teso’s visible representation in government, and he, smilingly disclaiming ethnic favoritism—may appear lighthearted on the surface. Yet beneath this choreography lies a deep anatomy of political psychology and the metaphysics of power in Uganda’s post-1986 republic.

1. The Politics of Gratitude: A Dangerous Commodity

When Speaker Among stood to thank the President for appointing Tesos to positions of power—the Vice President, the Speaker, the Deputy CDF, and several ministers—she unconsciously unveiled a colonial hangover: the politics of gratitude. In societies where patronage supplants institutional meritocracy, gratitude becomes both a survival instinct and a subtle confession of dependency.

It is not gratitude to the state—it is gratitude to the sovereign. Among’s tone, though well-intentioned, reflects a broader pathology in African governance where public office is perceived not as an entitlement of citizenship, but as a benevolent favor from the ruler.

In this sense, gratitude ceases to be virtue—it becomes submission masked as appreciation.

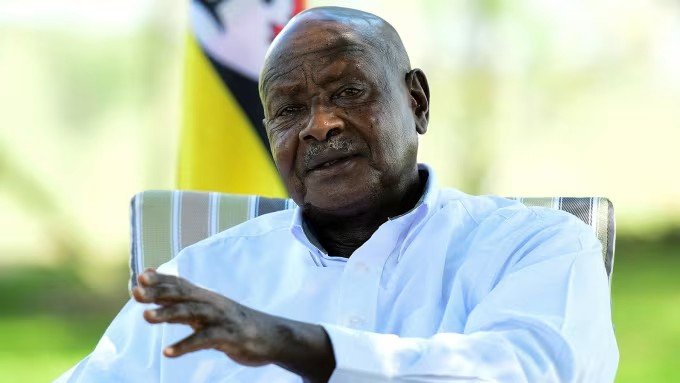

2. Museveni’s Smile: The Semiotics of Controlled Magnanimity

President Museveni’s response—“Hon. Among is going to cause me problems; people will say I love Teso more than everyone else!”—is at once humorous and politically strategic. The humor serves as a tranquilizer; it neutralizes the tribal undertone of Among’s remark while reasserting Museveni’s image as the impartial patriarch.

Yet, his follow-up—“I selected them based on merit, not because they are from Teso”—reveals something deeper. Museveni knows that Uganda’s post-colonial fault line is the question of identity versus merit. By invoking merit, he not only defends his own choices but also performs a symbolic purification of his legitimacy—reminding the audience that he transcends tribe, even as he presides over a mosaic of tribes.

This is classic Museveninomics of power—the art of appearing neutral while remaining omnipresent in every ethnic equation.

3. The Teso Paradox: Representation or Relevance?

To the people of Teso, this moment might symbolize inclusion. Yet inclusion without influence is a mirage. The Vice President from Teso may hold office, but does she hold sway? The Speaker may command Parliament, but does she command autonomy?

Ugandan political history teaches us that representation has never guaranteed transformation. The North once had ministers; Buganda had premiers; Busoga had loyalists; and yet, marginalization persisted. In Uganda’s administrative matrix, ethnic representation often functions as a pacifier—a symbolic token that sedates rather than empowers.

Thus, the Teso representation may be politically decorative but economically sterile.

4. The Metaphysics of Merit

When Museveni invokes merit, one must interrogate: whose merit, and by what metric?

In an environment where meritocracy dances with loyalty, and loyalty often outpaces competence, the line between qualification and allegiance blurs. The President’s statement thus becomes performative—a declaration meant to affirm fairness, even when fairness is selectively interpreted.

Merit becomes the new euphemism for trustworthiness to the regime, not necessarily excellence in governance. It is a moral camouflage that justifies political appointments in the vocabulary of virtue.

5. The Theology of Power in Uganda

This exchange is not simply about Teso; it is about the psychology of statehood in Uganda. The nation still operates under an unwritten theology: that power emanates from the patriarch’s will, and representation is his discretionary gift. It is a monarchic residue camouflaged within a republican vocabulary.

Every time a leader expresses gratitude for inclusion, it reaffirms the monarch’s divine right to exclude. And every time the patriarch smiles and says, “I chose them for their merit,” he reminds the nation that he alone is the arbiter of worth.

6. The Tragic Beauty of the Moment

There is something tragically beautiful about this exchange: the laughter, the humility, the illusion of consensus. It mirrors Uganda’s post-colonial paradox—a democracy wrapped in feudal psychology. Speaker Among’s warmth and Museveni’s wisdom are not in question; what is in question is the philosophical cost of gratitude in a republic that should owe everything to institutions, not individuals.

Conclusion: Between Grace and Governance

When gratitude becomes the currency of political exchange, merit becomes negotiable, and representation becomes ornamental. The Teso elite may occupy high offices, but the question remains—does Teso, as a region, rise with them?

Museveni’s laughter may have disarmed the crowd, but the statement lingered like an echo of Uganda’s enduring struggle: the tension between tribal symbolism and institutional strength, between the smile of inclusion and the silence of systemic control.

Uganda’s tragedy is not that her leaders are ungrateful—it is that her gratitude often blinds her to the need for structural emancipation.