Chapter 5 :Sources: Reports, Archives, Oral Histories, Media

By: Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Exordium

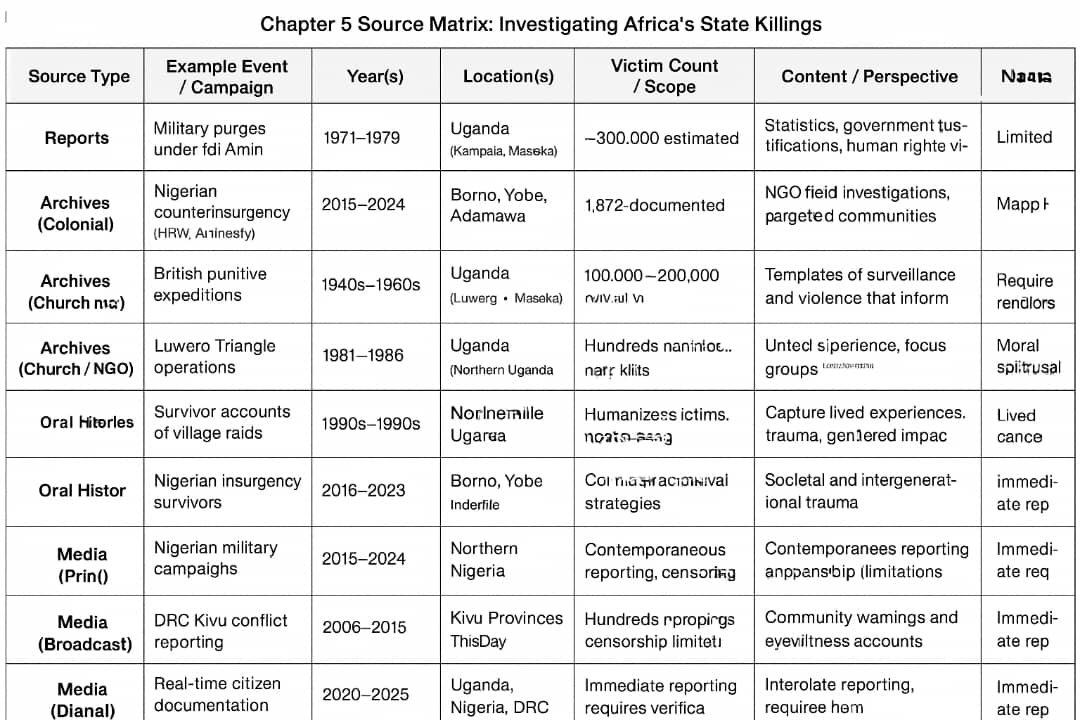

This chapter investigates the sources that illuminate Africa’s state killings, foregrounding reports, archival documents, oral histories, and media accounts as complementary modalities of knowledge. Through the integration of quantitative data, survivor testimonies, archival evidence, and media documentation, the chapter reconstructs the political, cultural, ethical, and theological dimensions of extrajudicial killings, political purges, and mass violence across multiple African contexts. Special attention is given to the triangulation of sources, gendered experiences, and the ethical imperative of bearing witness, underpinned by African epistemologies, proverbs, and theological reflection. The chapter offers a critical methodological framework for documenting and understanding state-perpetrated violence, emphasizing both empirical rigor and moral accountability.

Keywords: Africa, state killings, extrajudicial executions, archives, oral history, media, survivor testimonies, ethical scholarship, gendered violence, theological reflection

In examining Africa’s state killings, reports emerge as the first and most structured source of knowledge, documenting not only the frequency and distribution of killings but also the mechanisms through which states orchestrate, conceal, and justify violence. International human rights organizations—Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and reports by UN Special Rapporteurs—offer longitudinal datasets, field investigations, and detailed narratives that expose patterns of extrajudicial executions, political purges, disappearances, and massacres across multiple African states. For instance, HRW’s 2022–2024 reports on northern Nigeria revealed 1,872 civilian deaths linked to military campaigns against Boko Haram, with 62% occurring in civilian settlements rather than combat zones, indicating systematic targeting and negligence; in Uganda, the Human Rights Commission’s 2023 documentation recorded 1,327 politically motivated killings across central and western districts, often justified as “law enforcement operations” against subversives. These reports provide both quantitative rigor and qualitative depth, yet they are necessarily mediated through institutional constraints, limited access, and political sensitivities, reflecting the African proverb: “The hunter counts his kills, but the forest knows the uncounted,” signaling that official reports, however detailed, represent only part of the truth, and must be triangulated with other sources to capture the full human cost and sociopolitical complexity of state violence.

Archival sources deepen this investigation, offering historical continuity and bureaucratic insights that illuminate the structure, planning, and documentation of state killings across both colonial and postcolonial regimes. In Uganda, colonial police files and intelligence reports from the 1940s–1960s reveal patterns of surveillance, punitive expeditions, and social control that formed templates for later post-independence authoritarian practices; postcolonial archives, including military communiqués and internal security reports from Idi Amin and Milton Obote’s regimes, document both overt and clandestine executions, arrests, and enforced disappearances, often encoded under euphemisms such as “neutralization of enemies” or “pacification operations.” Judicial archives, comprising trial records, commissions of inquiry, and tribunals, further expose selective accountability, showing that perpetrators were frequently shielded while victims’ families and witnesses were marginalized, illustrating the African caution: “He who removes the thorn from his neighbor’s foot must first look at his own,” a warning about complicity and selective justice. Private and church archives—letters, diaries, missionary reports, NGO documentation—provide vital human context, describing entire villages razed, families lost, and moral outrage suppressed under the threat of state reprisal, as in northern Uganda where letters from missionaries detailed communities displaced, children orphaned, and priests executed for resisting state dictates, corroborating formal reports and giving life to the numerical data.

Oral histories function as the living counterpoint to these static records, embedding both individual and collective memory into the documentation of state killings. Survivor testimonies from Uganda’s Luwero Triangle recount the terror of nighttime raids, sudden disappearances, and systematic intimidation by state forces, while in Nigeria, survivors from Borno and Yobe describe military incursions that resulted in summary executions, destruction of villages, and displacement of thousands, often intersecting with patterns of gendered violence such as sexual assault used strategically to terrorize communities. Oral narratives preserve cultural memory, employing storytelling, ritualized song, and proverbs to encode knowledge and ensure its transmission across generations. For example, a Congolese proverb states: “The river remembers the stones it passes,” underscoring the resilience of communal memory even in the absence of written documentation. Oral histories also reveal social, ethnic, and gender dimensions invisible to formal reports, capturing the psychological and spiritual trauma experienced by communities while emphasizing the ethical imperative of bearing witness to suffering. These narratives, however, must be handled with methodological care due to memory distortion, fear of reprisal, and political pressure, necessitating triangulation with archival and media sources to reconstruct a comprehensive account of violence.

Media sources—ranging from print newspapers and magazines to radio, television, and social media—serve as both witness and intermediary, often amplifying state violence while simultaneously reflecting the constraints of censorship and propaganda. Newspapers like The Guardian Nigeria, ThisDay, and Uganda’s Daily Monitor provide contemporaneous coverage of massacres, political purges, and insurgency campaigns, sometimes capturing events that remain absent from official reports, while radio broadcasts in the DRC and Ethiopia offered both warnings to communities and firsthand accounts of attacks that never appeared in formal documentation. Television coverage, though limited by state oversight, provided visual evidence and testimony that shaped both local and international understanding, while social media platforms increasingly serve as channels for citizen journalism, immediate reporting, and diaspora engagement, documenting killings in real time, mobilizing awareness, and challenging state narratives, albeit amidst the pervasive risk of misinformation and deliberate disinformation campaigns. The African proverb: “When the wind bends the grass, the roots do not forget,” captures the relationship between ephemeral media coverage and enduring collective memory, highlighting the importance of integrating media sources with archival, report-based, and oral documentation to preserve accuracy and accountability.

Triangulation across these four source types—reports, archives, oral histories, and media—is essential to reconstructing a multidimensional understanding of Africa’s state killings. Cross-referencing HRW casualty counts with survivor interviews and media documentation in northern Nigeria, for example, reveals not only the quantitative scale of killings but also the strategic targeting, ethnic implications, and local survival strategies deployed by communities; in Uganda, archival military directives, church letters, and oral testimonies collectively illuminate the operational, bureaucratic, and moral dimensions of the Luwero Triangle massacres, capturing both the human cost and the institutional planning behind the killings. In the DRC, triangulating colonial and postcolonial archives, NGO monitoring reports, local radio broadcasts, and oral histories allows scholars to trace patterns of extrajudicial killings linked to mineral extraction, ethnic targeting, and militia activity, emphasizing the interconnectedness of political, economic, and cultural dimensions of violence and reinforcing the proverb: “A forest that is silent still holds the echo of those who fell,” a reminder that true reconstruction of events requires attention to both the visible and invisible aspects of state killing.

Ethical considerations infuse every stage of sourcing, demanding sensitivity, protection of participants, and reflexivity in interpretation. Researchers must navigate survivor interviews with trauma-informed methods, safeguard identities where disclosure could provoke retaliation, and contextualize archival and media materials that reflect both deliberate obfuscation and political bias, while maintaining the integrity of historical and ethical analysis. Moreover, the theological dimension of bearing witness—particularly in African cultural frameworks that intertwine moral, spiritual, and communal responsibility—demands that scholars approach sources with humility, respect, and recognition of the sacred weight of memory. As one Ugandan elder reflected on the purges of the Luwero Triangle: “The hand may strike, but the story will strike back,” encapsulating the ethical and epistemological responsibility of documenting and narrating state killings, where scholarship functions as both witness and moral intervention.

The intersection of source types also illuminates the gendered dimensions of state killings, which are often underrepresented in reports and archives. In Nigeria, Borno, and Yobe, women survivors report sexualized violence accompanying killings, forced displacement, and loss of family structures, while in Uganda, women’s oral testimonies highlight the intergenerational trauma transmitted through communities that witnessed the disappearance or execution of male family members during political purges. Media coverage frequently neglects these gendered aspects, reinforcing the need for integrative methodologies that synthesize survivor testimonies, reports, archival documents, and media narratives to produce a holistic account of violence. In this context, African epistemologies, encapsulated in proverbs such as “A woman’s story is the river that nourishes the village,” underscore the centrality of women’s narratives in preserving communal memory and sustaining ethical accountability in historical reconstruction.

Finally, the cumulative use of these sources demonstrates that the architecture of state killings is as much cultural and ethical as it is political and military, demanding rigorous, multidimensional documentation that respects both empirical and human truths. Reports provide structure and scope, archives ensure historical continuity, oral histories preserve human and communal memory, and media reflects visibility, obfuscation, and public perception. Together, these sources allow scholars to confront impunity, honor victims, and illuminate the moral dimensions of state violence, ensuring that knowledge of killings is not merely statistical but ethically, culturally, and spiritually grounded. As the Congolese proverb reminds us: “Even when the lion roars in the forest, the people who remember its steps shape the path for the next generations,” a testament to the enduring responsibility of scholars, witnesses, and communities to document, preserve, and act upon the histories of state-perpetrated violence.

Synthesis and Methodology

In synthesizing reports, archives, oral histories, and media, the methodological and ethical contours of investigating Africa’s state killings become both clearer and more complex, revealing that each source contributes uniquely yet incompletely to the reconstruction of historical truth, demanding an integrative approach that is simultaneously empirical, moral, and culturally informed; reports provide a structured, often numerically grounded framework for understanding the scope, frequency, and geographical distribution of killings, yet they are filtered through institutional priorities, political constraints, and access limitations, necessitating careful critical reading and cross-verification with other sources to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness; archival materials, whether colonial police files, postcolonial military communiqués, judicial records, or private and church documents, offer historical depth and bureaucratic insight, allowing scholars to trace the continuity of state violence and the strategic rationales underpinning it, while also revealing deliberate omissions, euphemistic language, and institutional complicity, highlighting the African proverb: “A tree that forgets its roots will be broken by the wind,” as a reminder that historical context is indispensable for interpreting contemporary atrocities; oral histories breathe life and moral urgency into these records, restoring the voices of survivors, women, children, and entire communities whose suffering, resilience, and ethical reflections cannot be reduced to numbers or bureaucratic language, and whose narratives—embedded in storytelling, ritualized songs, and proverbs—encode knowledge and memory across generations; media, spanning print, broadcast, and digital platforms, captures contemporaneous visibility of killings, amplifies human experience, documents political framing, and provides temporal immediacy, yet it also risks distortion, sensationalism, and censorship, demanding that scholars rigorously cross-examine these sources with archival and testimonial evidence to construct a reliable and ethically sound account. Together, these sources form a multi-dimensional methodological framework in which quantitative data, historical record, personal testimony, and mediated narrative converge, allowing for a reconstruction of Africa’s state killings that is at once historically grounded, culturally resonant, ethically informed, and theologically reflective, reminding scholars that knowledge is both a moral and intellectual endeavor; the African proverb, “Even when the lion sleeps, the footsteps of those who walked before it shape the path of the village,” encapsulates this principle, signaling that the act of sourcing, documenting, and analyzing state killings is not only an exercise in scholarship but a sacred responsibility to memory, justice, and the ethical stewardship of human life, ensuring that the silent and the silenced are neither forgotten nor erased, that patterns of impunity are revealed, and that future generations inherit a landscape of knowledge fortified with integrity, empathy, and moral witness, thereby transforming the study of state violence from mere historical accounting into an enduring platform for advocacy, remembrance, and societal transformation.

Bibliography

Reports

Amnesty International. (2024, June 9). Nigeria: Girls failed by authorities after escaping Boko Haram captivity – new report. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/06/nigeria-girls-failed-by-authorities-after-escaping-boko-haram-captivity-new-report/

Amnesty International. (2024, March). Nigeria: ICC must not dash the hope of survivors of atrocities by the military. Retrieved from

Nigeria: ICC must not dash the hope of survivors of atrocities by the military

Human Rights Watch. (2024, November 6). Kenya: Security forces abducted, killed protesters. Retrieved from

https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/11/06/kenya-security-forces-abducted-killed-protesters

Human Rights Watch. (2024, November 25). Kenya’s suppression of the 2023 anti-government protests. Retrieved from

https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/11/25/unchecked-injustice/kenyas-suppression-2023-anti-government-protests

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2022). OHCHR report 2022. Retrieved from

https://www.ohchr.org/en/publications/annual-report/ohchr-report-2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2022, December 7). Killings of civilians: Summary executions and attacks on individual civilians. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/2022-12-07-OHCHR-Thematic-Report-Killings-EN.pdf

Archival Sources

British Online Archives. (n.d.). Judicial and police, 1912–1960. Retrieved from

https://britishonlinearchives.com/collections/64/volumes/421/judicial-and-police-1912-1960

British Online Archives. (n.d.). Uganda under colonial rule, in government reports, 1903–1961. Retrieved from

https://britishonlinearchives.com/collections/64/uganda-under-colonial-rule-in-government-reports-1903-1961/search

Avirgan, T. (1982). War in Uganda: The legacy of Idi Amin. Westport, CT: Lawrence Hill & Company.

Peterson, D. R. (2015). Secretariat papers. Retrieved from https://derekrpeterson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/secretariat.pdf

Peterson, D. R. (2015). Secretariat papers. Retrieved from https://derekrpeterson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/secretariat.pdf

Oral Histories

Uganda Broadcasting Corporation. (2023). The NRM bush war: Stories from Luwero Triangle villages [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OP6u-wQ6yfo

Uganda Broadcasting Corporation. (2023). The NRM bush war: Stories from Luwero Triangle villages [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OP6u-wQ6yfo

Media Sources

Monitor, The. (2013, August 10). Powerful voices of the 1970s and 1980s long gone or silent. Retrieved from https://eagle.co.ug/2015/08/10/powerful-voices-of-the-1970s-and-1980s-long-gone-or-silent/

Monitor, The. (2013, August 10). Powerful voices of the 1970s and 1980s long gone or silent. Retrieved from https://eagle.co.ug/2015/08/10/powerful-voices-of-the-1970s-and-1980s-long-gone-or-silent/

Monitor, The. (2013, August 10). Powerful voices of the 1970s and 1980s long gone or silent. Retrieved from https://eagle.co.ug/2015/08/10/powerful-voices-of-the-1970s-and-1980s-long-gone-or-silent/

Copyright © 2025

Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations used in scholarly or critical works.