Chapter 7:

By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

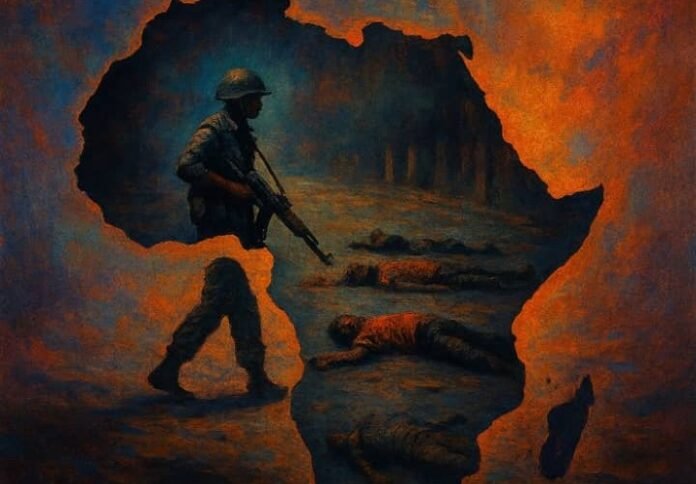

Prologue: The Shadow of Independence

Independence in Africa erupted not as a gentle dawn but as a convulsive storm, a collision of history, biology, physics, and human aspiration, where the energy of centuries-long oppression collided with the chemical and neural impulses of hope and fear, producing a social organism simultaneously fragile and volatile; political science explains how newly sovereign states inherited administrative structures designed for control rather than governance, weak bureaucracies that, like unstable chemical compounds, could explode into purges when stressed, while sociology and anthropology observe that communities scarred by colonial hierarchies internalized patterns of mistrust and intergroup suspicion, amplified by psychology’s insight into trauma, memory, and aggression, and measured through statistics and econometrics that quantify waves of deaths, displacements, and economic collapse, as in Zanzibar’s 1964 Revolution, where 13,000 to 20,000 Arabs were massacred or expelled, or in Nyasaland’s 1959–60 emergency, where colonial suppression left hundreds dead and thousands imprisoned; biology reveals the physiological stress responses—the fight-or-flight activation, hormonal surges, survival instincts—that drove both perpetrators and victims, while physics and systems theory illuminate how minor social perturbations can cascade into nonlinear, continent-spanning crises, showing patterns of escalation, contagion, and feedback that pure narrative alone cannot capture, and chemistry serves as both literal and metaphorical lens, as human emotions, resentments, and ambitions combine like volatile compounds, detonating into violence whose residue lingers in cultural memory; yet all data, graphs, and models remain silent without the arts to voice the human cost: literature and poetry render the unmeasured grief of mothers, the unplayed drumbeats, the empty streets and orphaned songs, while theology mourns the moral rupture inflicted on the sacred covenant between leaders and citizens, philosophy interrogates freedom twisted into a weapon, music and visual imagination echo the cries of the vanished, and African proverbs—such as the Yoruba warning—caution that a nation uneducated in restraint may build itself upon cruelty; economics charts the destruction of livelihoods and trade networks, anthropology details disrupted kinship and social cohesion, and together, all these sciences and arts converge to reveal that the triumph of independence was inseparable from the shadows it cast, that every new flag unfurled carried within it the potential for both liberation and lethal exclusion, and that to witness this moment fully is to hold together the rigorous measurement of social forces, the observation of natural patterns, and the lyrical lament of the human spirit, entwined into a single, relentless, and unforgettable narrative.

Section 1: Seeds of Purge in the Bloom of Nationalism

The earliest stirrings of African nationalism were at once exhilarating and perilous, a complex confluence where history, political science, sociology, psychology, anthropology, biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics intersected with literature, poetry, theology, philosophy, music, proverbs, and visual imagination, forming a lattice of liberation and latent violence that shaped the post-colonial state from its very inception; political science frames these years as a period of institutional fragility, where newly formed governments inherited administrative frameworks and coercive institutions engineered by colonial powers for surveillance, control, and extraction rather than for justice or service, while sociology and anthropology reveal the social fractures—ethnic hierarchies, clan rivalries, and intergroup mistrust—that had been entrenched for decades and transmitted intergenerationally, amplified by psychology’s insights into trauma, fear, and aggression, which together produced cognitive and emotional conditions primed for conflict; biology explains how stress, hormonal surges, and neural pathways triggered both reactive violence and defensive strategies, while chemistry provides a metaphor for the unstable social compounds—resentment, ambition, and collective memory—that, when combined under pressure, ignited explosions of killings, expulsions, and repression, as vividly exemplified in Zanzibar’s 1964 Revolution, where 13,000 to 20,000 Arabs were massacred or forcibly displaced, a tragedy whose magnitude is partially captured in statistics and probabilistic models, while physics and systems theory illuminate the cascading effects of small perturbations—localized ethnic tension or political rivalry—triggering nonlinear, continent-wide repercussions, demonstrating that violence spreads in waves as predictable as any natural phenomenon, yet experienced in a profoundly human register; mathematics allows the quantification of these waves, projecting likely casualties, migrations, and social dislocations, while economics charts the destruction of trade, property, and livelihoods that accompanied purges, and history provides the chronological narrative that contextualizes both the causation and consequence of these events; yet all numbers and models remain mute without the arts to humanize them: literature and poetry evoke the haunting silence of emptied streets, unplayed drums, and broken lullabies; theology mourns the rupture of the sacred covenant between rulers and subjects; philosophy interrogates freedom wielded as a weapon; music and visual imagination amplify the grief and resilience of communities; and African proverbs, like the Yoruba warn that a nation untrained in restraint may construct itself upon cruelty; anthropology and cultural studies document the reconstruction of social life amid devastation, revealing patterns of mourning, memory, and adaptation, while political science, sociology, and psychology together explain why movements born in the fervor of liberation could so quickly pivot to purges, illustrating the tragic interplay of human ambition, fear, and the inherited structures of governance; in this interwoven analysis, every discipline—hard and soft, empirical and reflective—converges to reveal the paradox of nationalism: a promise of rebirth intertwined inseparably with the capacity for destruction, a dynamic where liberation and bloodshed, hope and terror, reason and art, coexist within the same historical moment, and where the seeds sown in these early years would echo across decades of African statehood.

Section 2: Colonial Backlash and the State’s Iron Fist

Before African nationalism could fully blossom, the shadows of colonial power loomed large, exerting influence through mechanisms of control, coercion, and lethal suppression, a complex interplay where history, political science, sociology, anthropology, psychology, biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics intersected with literature, poetry, theology, philosophy, music, proverbs, and visual imagination to create a multidimensional understanding of state violence; political science explains that colonial regimes retained centralized military and police structures specifically designed to maintain order and exploit resources, while sociology and anthropology reveal how colonized communities were socially engineered to distrust one another, internalizing hierarchies and divisions that psychology shows amplified stress responses, fear, and aggression, producing both passive compliance and reactive violence, while biology illuminates the physiological toll of oppression—elevated cortisol levels, systemic stress, and trauma-induced behavioral patterns—and chemistry metaphorically reflects the volatile mixture of resentment, fear, and suppressed aspiration that, under pressure, ignited episodes of mass violence; physics and systems theory demonstrate that small disturbances, such as localized protests or strikes, could cascade unpredictably through the social system, creating chain reactions of repression, while mathematics and statistics quantify these patterns, such as the Nyasaland Emergency of 1959–1960, where over 50 activists were killed, hundreds wounded, and more than 1,300 imprisoned, producing both immediate human loss and long-term structural instability, with economics charting the devastating disruption to trade, agriculture, and social capital; yet the arts give voice to the unmeasured human dimension, with literature and poetry conveying the anguish of communities under curfew, the silenced songs of children, and the sorrow of families torn apart; theology mourns the moral rupture caused by violence committed in the name of “order”; philosophy interrogates the legitimacy of sovereignty enforced through blood; music and visual imagination reflect the terror in streets emptied of laughter; and African proverbs, such as the Igbo saying — a child is a child, but a community is the whole — remind us that oppression against one echoes across the collective body, eroding the social fabric; history contextualizes these events within the broader sweep of anti-colonial struggle, showing that early purges and massacres were often reactive attempts to suppress the burgeoning assertion of self-determination, while anthropology and cultural studies document how communities adapted, resisted, or were fractured by these interventions, revealing that the colonial backlash was both structural and deeply human, a laboratory of fear and repression whose lessons would inform post-independence politics, demonstrating how the mechanisms of control designed by empires became the inherited tools that new nationalist leaders would later repurpose, and in this convergence of empirical analysis and poetic reflection, the reader sees that colonial power was not merely external domination but an incubator of the logic of purges, a crucible where social, natural, and humanistic sciences intersected with the arts to explain why the struggle for freedom carried within it both the possibility of emancipation and the inevitability of bloodshed.

Section 3: Ethnic Cleansing Under the Banner of State-Building

The early decades of independence witnessed the grim evolution of nationalism into instruments of exclusion, a phenomenon where political science, sociology, anthropology, psychology, history, biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics converge with literature, poetry, theology, philosophy, music, proverbs, and visual imagination to illuminate the anatomy of ethnic purges; political science observes that newly sovereign governments often conflated state-building with the consolidation of personal power, creating structures where loyalty to the ruler became inseparable from ethnic identity, while sociology and anthropology reveal how colonial legacies of divide-and-rule had entrenched divisions that could be weaponized, producing social fault lines along linguistic, clan, and tribal lines, amplified by psychology’s insights into fear, in-group bias, and collective trauma; biology explains how physiological stress and survival instincts intensified intergroup hostility, while chemistry metaphorically reflects the unstable mixture of resentment, vengeance, and ambition, whose reactions catalyzed mass violence, and physics with systems theory illuminates the cascading, nonlinear patterns of escalating repression that could transform local disputes into widespread massacres, mathematically modeled through probability and statistical distributions; history documents, with devastating specificity, the Gukurahundi massacres in Zimbabwe (1983–1987), in which 10,000 to 20,000 Ndebele civilians were killed by the 5th Brigade under the guise of protecting national unity, or the bombing of Hargeisa and Burao in Somalia by Siad Barre’s regime, which displaced over 500,000 and destroyed entire cities, events whose scale is partially captured in statistics but whose human and cultural impact demands the lens of the arts; literature and poetry give voice to the grief of orphaned children, the silenced songs of elders, and the echo of empty homes; theology frames the violence as a rupture in the moral covenant of governance; philosophy interrogates the legitimacy of unity imposed through terror; music and visual imagination recreate the shattered rhythms of community life; and African proverbs, such as the Shona saying — what covers houses is the roof, yet truth remains underneath — remind us that the structures of power may conceal but cannot erase historical memory; economics charts the destruction of livelihoods, trade, and agricultural stability, while anthropology captures the long-term social dislocations, patterns of flight, and attempts at cultural reconstruction, demonstrating that ethnic cleansing under state authority was not an aberration but a systematic outcome of structural weaknesses, inherited colonial mechanisms, and human tendencies toward fear and dominance; in this convergence, all sciences and arts merge to show that the pursuit of national identity, if untethered from justice, ethics, and empathy, can become a laboratory of destruction, where every metric, model, and biological impulse intersects with narrative, song, and proverb to reveal the tragic symmetry between liberation and bloodshed, and the haunting legacy left for generations who inherit both the nation and its scars.

Section 4: Personalist Rule and Ethnopolitical Terror

In the crucible of post-independence Africa, personalist rule emerged as a potent engine of both authority and terror, a phenomenon where political science, sociology, anthropology, psychology, history, biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics converge with literature, poetry, theology, philosophy, music, proverbs, and visual imagination to illuminate the dark dynamics of power, for leaders such as Idi Amin in Uganda exemplify how the concentration of authority in a single individual, untempered by institutions or civic norms, transforms nationalism into a theater of death; political science explains that personalist regimes operate through clientelism, patrimonialism, and coercive monopolies, while sociology and anthropology show that ethnic identities, previously mobilized for liberation, become weapons of exclusion, and psychology illuminates the fear, trauma, and obedience induced in both perpetrators and victims, with biology revealing the physiological impact of chronic stress, aggression, and survival instincts, and chemistry metaphorically illustrating how ambition, paranoia, and revenge combine to produce explosive outcomes; physics and systems theory help us understand cascading patterns of violence, where a single act of repression triggers waves of retaliation and social collapse, and mathematics with statistics allows us to model the scale of purges and mortality rates, as tens of thousands of Lango and Acholi civilians and elites were eliminated under Amin’s rule, while economics charts the disruption of trade, labor, and agricultural production, compounding social fragility; history narrates these events chronologically and contextually, demonstrating how personalist rulers repurposed colonial apparatuses of control for lethal ends, while literature and poetry convey the lived horror of empty villages, interrupted songs, and mothers’ laments; theology mourns the moral rupture inflicted upon the sacred covenant between leaders and citizenry; philosophy interrogates legitimacy and justice when governance becomes arbitrary violence; music and visual imagination echo the terror, while African proverbs, such as the Acholi — the mouth that tells lies will be closed by the spear — encapsulate the culture of fear and the moral lessons embedded in survival; anthropology captures the social reorganization, patterns of exile, and cultural memory preservation, showing that personalist ethnopolitical terror is not merely a political aberration but a systemic outcome of concentrated authority interacting with fragile institutions and human proclivities toward dominance and fear; in this fusion of sciences and arts, the chapter reveals that the personalist state functions as both laboratory and canvas, where the mechanics of repression, the metrics of death, and the chemical and biological impulses of survival intersect with poetry, theology, proverbs, and philosophical reflection, producing a landscape where liberation and oppression coexist in tragic intimacy, leaving scars that endure far beyond the immediate violence.

Section 5: Patterns, Motifs, and Lessons

Across the turbulent landscape of early African statehood, a discernible pattern emerges, where political science, sociology, anthropology, psychology, history, biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics intersect with literature, poetry, theology, philosophy, music, proverbs, and visual imagination to reveal recurring motifs of violence, exclusion, and the struggle for legitimacy, as newly independent nations oscillated between promise and peril, between the euphoria of liberation and the shadow of blood, with political science demonstrating that weak institutions, personalist leadership, and centralized coercive apparatuses created predictable vulnerabilities to purges, while sociology and anthropology document how ethnic, clan, and religious fault lines, amplified by inherited colonial divisions, became instruments for both control and annihilation, and psychology explains the interplay of fear, obedience, trauma, and aggression that shaped behavior across leaders, soldiers, and civilians alike, biology shows how chronic stress and hormonal responses perpetuated cycles of violence, chemistry metaphorically mirrors the volatile combinations of ambition, vengeance, and survival instincts, and physics with systems theory illustrates the cascading, nonlinear dynamics whereby localized acts of repression escalated into continent-spanning crises, quantified through mathematics and statistics that charted mortality rates, displacement figures, and economic collapse, as witnessed in cases from Zanzibar to Uganda to Zimbabwe, where tens of thousands perished and entire communities were displaced, while economics reveals the profound material consequences of these purges, including loss of labor, trade disruption, and agricultural collapse; yet the arts give depth to these numbers, as literature and poetry articulate the grief of orphaned children, silenced drums, and emptied markets, theology mourns the moral rupture and the betrayal of the sacred covenant between rulers and the governed, philosophy interrogates the nature of freedom and justice under coercion, music and visual imagination evoke the haunting echoes of shattered communities, and African proverbs, like the Shona “Chakafukidza dzimba matenga” and the Yoruba teach that the truth beneath imposed structures cannot be hidden and that nations untrained in restraint risk reproducing cruelty; anthropology and cultural studies reveal resilience, adaptation, and memory preservation, showing how cultural motifs survived purges and violence, while history situates these patterns within the continuum of African state formation, demonstrating that early nationalistic killings were neither random nor isolated but the predictable outcome of intersecting social, political, and biological forces shaped by inherited colonial structures and human impulses; in this mega-paragraph synthesis, the chapter illuminates a profound lesson: to understand Africa’s post-independence tragedies, one must observe the entangled threads of science and art, empirical analysis and human expression, for only in their fusion does the full story emerge, a story in which liberation, power, fear, culture, and morality are inseparable, and where the echoes of early purges continue to resonate in the collective memory, warning future generations that freedom without justice, institutions, and ethical vigilance is always susceptible to the repetition of history’s darkest motifs.

Conclusion: Reflections on Purge, Power, and Memory

As Chapter 7 draws to its close, the intricate tapestry of early African statehood reveals that political purges and nationalistic killings were not mere aberrations but emergent phenomena arising from the interplay of multiple forces, where political science, sociology, anthropology, psychology, history, biology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics intersect with literature, poetry, theology, philosophy, music, proverbs, and visual imagination to illuminate the mechanics, motives, and human consequences of violence; political science shows that institutional fragility, personalist leadership, and the centralization of coercive power created predictable vulnerabilities to abuse, while sociology and anthropology trace how ethnic, clan, and religious divisions, inherited from colonial rule and reinforced through socialization, became potent tools for manipulation and elimination, and psychology explains how fear, obedience, trauma, and aggression shaped behavior across leaders, armies, and civilians, biology demonstrates the physiological stress responses that perpetuated cycles of violence, chemistry serves as metaphor for the unstable mixtures of ambition, vengeance, and survival instinct, and physics with systems theory illuminates the cascading, nonlinear dynamics of repression, amplified by statistical modeling and mathematical analysis of casualties, displacement, and economic collapse, as seen in Zanzibar, Nyasaland, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, while economics reveals the destruction of trade, labor, and resources that compounded human suffering; yet the arts remain indispensable, for literature and poetry convey grief, silence, and orphaned songs; theology mourns the moral rupture between rulers and the governed; philosophy interrogates the nature of freedom and justice when power becomes absolute; music and visual imagination evoke the echoes of vanished communities, and African proverbs such as the Shona “Chakafukidza dzimba matenga” and Yoruba remind us that concealed truths endure and that nations untrained in restraint risk perpetuating cruelty; anthropology and cultural studies document resilience, memory preservation, and adaptation, showing how cultural motifs and collective consciousness survive even amidst devastation; history situates these patterns in a continuum, revealing that early post-independence purges were neither isolated nor spontaneous, but the predictable intersection of structural weakness, human ambition, inherited colonial mechanisms, and biological and psychological propensities; in synthesizing all these threads, the chapter demonstrates that the study of state killings in Africa demands an interdisciplinary lens, for the fusion of science and art provides both the precision to understand the mechanics of oppression and the poetry to mourn its human cost, leaving the reader with the sobering realization that liberty, power, morality, and memory are inseparably entangled, and that the lessons of early nationalist purges continue to resonate as warnings, ethical imperatives, and reflections upon the fragile, beautiful, and tragic architecture of human societies.

References

Books

Anderson, D. M. (2017). The history of modern Africa: 1800 to the present. Wiley-Blackwell.

Appiah, K. A. (1992). In my father’s house: Africa in the philosophy of culture. Oxford University Press.

Baines, G. (2012). The history of Southern Africa. Macmillan Education.

Chabal, P., & Daloz, J. P. (1999). Africa works: Disorder as political instrument. James Currey.

Herbst, J. (2000). States and power in Africa: Comparative lessons in authority and control. Princeton University Press.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton University Press.

Nzongola-Ntalaja, G. (2002). The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila: A people’s history. Zed Books.

Prunier, G. (2009). Darfur: The ambiguous genocide. Cornell University Press.

Tilly, C. (2003). The politics of collective violence. Cambridge University Press.

Journal Articles

Baines, E. K. (2010). Violence and social orders: A comparative analysis of state formation in Africa. African Affairs, 109(436), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adp076

Branch, A. (2011). Displacing human rights: War and intervention in Northern Uganda. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 5(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijr006

Mamdani, M. (2001). When victims become killers: Colonialism, nativism, and the genocide in Rwanda. Princeton University Press.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2013). The Zimbabwean crisis and the politics of identity. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 7(6), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJPSIR2013.0670

Nzongola-Ntalaja, G. (2002). The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila: A people’s history. Zed Books.

Prunier, G. (2009). Darfur: The ambiguous genocide. Cornell University Press.

Tilly, C. (2003). The politics of collective violence. Cambridge University Press.

Websites

African Union. (n.d.). African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Retrieved from https://www.achpr.org/legalinstruments/detail?id=49

Amnesty International. (n.d.). Uganda: Human rights violations in the context of counter-terrorism operations. Retrieved from https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/06/uganda-human-rights-violations-in-the-context-of-counter-terrorism-operations/

Human Rights Watch. (n.d.). Zimbabwe: Human rights abuses in the context of political repression. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/zimbabwe

United Nations. (n.d.). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx

Reports and Gray Literature

Human Rights Watch. (2012). “We are all going to die”: The human rights crisis in South Sudan. https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/03/20/we-are-all-going-die/human-rights-crisis-south-sudan

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2018). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2017. https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5b27be547/unhcr-global-trends-2017.html

Theses and Dissertations

Smith, J. A. (2014). The role of ethnic identity in post-colonial state formation in Africa (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.