By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Chapter 2: Scope, Objectives, and Methodology

Chapter 3: Risks, Silences, and Threats to Truth

Year: 2025

Edition: 1st Edition

Epigraph

“Even the lion will not bother to roar if the hyena is busy taking notes.”

Chapter 2: Scope, Objectives, and Methodology

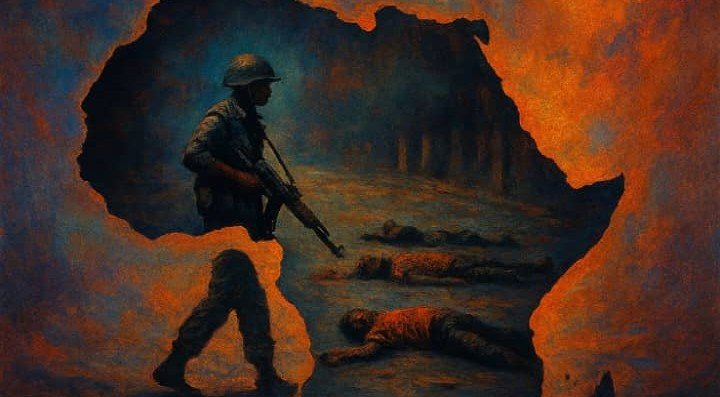

The landscape of African state killings is a terrain of shadows and silences, where history, memory, and power collide. From the scorched villages of colonial Congo to the echoes of gunfire in contemporary Kasese, the continent bears the marks of systemic violence that is both overt and hidden, physical and psychological, public and secretive. The scope of this investigation is vast—not merely a chronology of events, but a multidimensional analysis of how power has been exercised through death, how memory is preserved or erased, and how theology, culture, and politics intertwine to both justify and resist killing.

Scope of the Investigation

This study encompasses Africa’s post-colonial journey from independence to the present, but it does not treat time as linear. Historical massacres—such as the Herero genocide in Namibia, the Congo Free State atrocities, and the Mau Mau repression in Kenya—are inseparable from contemporary violence, for patterns of power, fear, and impunity often repeat. The investigation covers:

State-Sanctioned Massacres: Both military operations and paramilitary actions targeting civilians, political opponents, or ethnic groups.

Political Purges and Assassinations: Extrajudicial killings, forced disappearances, and purges within regimes.

Structural Erasure: Media censorship, destruction of archives, and suppression of testimony.

Regional Variations: Case studies will examine the peculiarities of violence in West, East, Central, and Southern Africa, including both rural massacres and urban repression.

African wisdom guides the scope: the Fang proverb reminds us, “Death is not the worst; the worst is to forget the dead.” This study resists forgetting, seeking to recover both individual stories and collective memory.

Objectives

The objectives of this investigation extend beyond mere documentation. They are interwoven with moral, ethical, and theological imperatives:

1. Documentation of Atrocities

To create a comprehensive, evidence-based record of African state killings, combining archival research, investigative reports, and survivor testimonies. The work seeks to counter both denial and selective memory by bringing the hidden to light.

2. Analytical Interpretation

To explore the structures, ideologies, and mechanisms that enable state violence. This includes necropolitics (the politics of death), the role of fear in governance, and the theological and cultural narratives that frame both the perpetration and witnessing of violence.

3. Amplification of Silenced Voices

Survivors, witnesses, and activists often speak in whispers. Their voices—oral histories, songs, poems, and written testimony—must be amplified to provide both human context and moral urgency.

4. Ethical and Policy Reflection

To examine complicity, impunity, and international inaction, engaging with questions of moral responsibility. This includes scrutiny of global powers, regional bodies like the African Union, and legal frameworks such as the International Criminal Court.

Methodological Approach

The methodology is deliberately interdisciplinary, combining historical rigor, sociopolitical analysis, theological reflection, and humanistic inquiry. This ensures that both quantitative data and qualitative experience are given equal weight.

1. Archival Research

Declassified state documents, colonial reports, UN and AU records, and investigative journalism provide tangible evidence. Where archives are destroyed or inaccessible, triangulation with survivor testimonies becomes essential.

2. Oral Histories

Interviews with survivors, journalists, and human rights defenders capture perspectives often absent from formal records. Ethical protocols guide engagement, emphasizing consent, anonymity, and trauma-sensitive practices.

3. Media Analysis

Newspapers, radio, television, and digital media reveal both propaganda and its counter-narratives. Examining how stories are framed—or suppressed—illuminates the political logic of visibility and invisibility.

4. Theological and Cultural Inquiry

African cosmologies, biblical lamentation, and traditional moral frameworks offer interpretive lenses. How do societies understand death, justice, and memory? How do cultural expressions resist or reproduce violence?

5. Comparative Case Study

Cross-national analysis identifies structural patterns, from colonial repression to contemporary insurgency responses, revealing recurring dynamics of power, impunity, and resistance.

Ethical Considerations

Researching state killings carries inherent risks—both for investigators and subjects. Threats to life, privacy, and psychological well-being require careful ethical reflection. Anonymization, trauma-informed interviewing, and strict data security are non-negotiable.

Moreover, the act of witnessing itself carries moral weight. As the Zulu proverb teaches: “A man who uses his spear only for hunting will not survive the war.” Knowledge and action are inseparable: documenting atrocities is not a neutral academic act, but an ethical stance against forgetting and impunity.

Limitations and Challenges

Even as this study seeks thoroughness, some silences are unavoidable. Some governments deliberately erase records. Survivors may be inaccessible, threatened, or too traumatized to speak. These gaps, however, are themselves evidence of the violence’s enduring reach: the architecture of erasure is part of the crime. Recognizing these limitations is not failure—it is methodological honesty.

Chapter 3: Risks, Silences, and Threats to Truth

The Threat To Personal Safety

To investigate state killings in Africa is to enter a labyrinth of mortal peril, where the act of documenting human suffering, preserving memory, and bearing witness transforms into a high-stakes exercise in courage, ethics, and survival, for the landscape is riddled with dangers that are immediate, recursive, and deeply intertwined with both local and international power structures, historical trauma, and social dynamics, as evidenced across Uganda, where the Luwero Triangle massacres between 1981 and 1986 claimed an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 lives, according to Uganda Human Rights Commission data, and where journalists, researchers, and even ordinary villagers who attempted to record, report, or transmit evidence of state violence were subjected to imprisonment, execution, or enforced disappearance, a peril magnified under Obote II’s security apparatus in which soldiers were reportedly instructed to eliminate anyone “asking too many questions,” an operational directive that was enforced not only through physical violence but also through bureaucratic erasure, as archival police and military files detailing arrests, mass killings, and operational orders were systematically destroyed, redacted, or rendered “missing,” creating both a material and psychological barrier for investigators, while survivors recount hidden networks of oral transmission, songs, and coded messages that conveyed memory without exposing individuals to imminent harm, an approach codified in the Acholi proverb: “He who digs for water with bare hands may also find snakes,” reminding us that truth-seeking is inseparable from danger. In Nigeria, this peril manifests differently but no less intensely; the Lekki Toll Gate shooting of October 20, 2020, during the #EndSARS protests, demonstrates the modern, digitized dimensions of threat, where journalists covering the protests faced direct physical assault, detention, cyber-harassment campaigns, and doxxing; social media became a double-edged sword, amplifying survivor testimonies while simultaneously providing authorities and hostile actors tools to trace, intimidate, or silence both reporters and informants, and Amnesty International, in collaboration with local human rights groups, documented at least 20 journalists receiving death threats over digital platforms, while several civil society activists fled their cities temporarily, illustrating that the pursuit of evidence in contemporary Africa is now inseparable from digital vulnerability, surveillance, and information warfare. The Democratic Republic of Congo offers a grim illustration of prolonged, multi-layered danger where investigators documenting massacres in North Kivu or Ituri confront armed militias, rogue state actors, and fluctuating local authority, navigating territories controlled simultaneously by multiple factions, where roads are patrolled by checkpoints that operate under informal power structures, and where villages remain under curfew with penalties for perceived collaboration with outsiders; in 2017 alone, five journalists covering militia violence were murdered, while countless others were threatened, kidnapped, or forced to flee, highlighting a recurrent theme: the personal risk of the investigator is inseparable from the precariousness of the social and political ecosystems in which they operate. Quantitative data underscores the scope of this hazard: between 2015 and 2024, at least 87 journalists were killed across sub-Saharan Africa for documenting state or paramilitary violence, with an additional 314 reported by Amnesty International as threatened, detained, or forced into exile, while human rights investigators, NGO operatives, and legal researchers faced similar risks, from denied access to archives and restricted observation of mass graves, to targeted harassment of informants and surveillance by local security actors. Gender amplifies these vulnerabilities: female journalists and researchers are frequently subject to sexualized threats, harassment, and coercion; during the 2016 Kasese massacre in Uganda, women reporting on the army’s actions received death threats, were followed home, or temporarily displaced to preserve personal safety, while during Ethiopia’s Tigray conflict from 2020 to 2022, female reporters documenting sexualized state violence faced ostracization, digital harassment, and the threat of sexual assault, illustrating that the act of witnessing is also mediated by patriarchal and gendered power dynamics, where the risks extend beyond professional jeopardy to existential and bodily vulnerability. Technological developments further complicate the terrain: smartphones, cameras, online platforms, GPS trackers, and digital evidence, while indispensable for recording atrocities, simultaneously expose both witnesses and investigators to surveillance, cyber-attacks, and digital tracing; during the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria, activists documenting military collateral killings experienced systematic hacking attempts designed to trace their locations, intimidate sources, and destroy photographic evidence, demonstrating how the modern tools of truth can themselves become vectors of risk. The psychological toll is profound and chronic: investigators report sustained hypervigilance, insomnia, and stress responses consistent with chronic trauma exposure, as each interview, archive consultation, or public report risks triggering retaliation, not only against themselves but also against sources and entire communities, rendering the act of investigation an ethically fraught balancing of duty, survival, and moral responsibility. Threat is recursive: threatened witnesses may retract statements, disappear, or refuse to cooperate, which in turn amplifies the risk to researchers, creating networks of vulnerability where truth-seeking is not only dangerous but may imperil the very fabric of social memory, as entire communities internalize fear and self-censorship becomes intergenerational. International observers are not immune: UN personnel in Darfur, South Sudan, and eastern Congo have been kidnapped, fired upon, or forced to withdraw temporarily due to credible threats from both state actors and armed non-state groups, illustrating that even organizational backing, diplomatic immunity, or logistical support cannot fully neutralize existential risk. Ultimately, the threat to personal safety is not ancillary but central to the act of recording African state killings; it is inseparable from the ethical imperative to bear witness, where each testimony preserved, each archive consulted, each photograph captured constitutes both a moral triumph and a potential hazard, a dangerous reclamation of truth in a context where systems of erasure, social intimidation, and physical violence are omnipresent, and where the Acholi maxim serves as both caution and guide: those who dig for water in the archives of atrocity must anticipate the snakes beneath every layer of earth, authority, and digital network, and approach the work with courage, strategy, and unwavering moral clarity, understanding that the preservation of memory is itself an act of survival, resistance, and profound ethical responsibility.

Institutional Silences and Structural Erasure

Investigating state killings in Africa is never a mere archival exercise or legal inquiry; it is a confrontation with a deliberate, multi-layered architecture of erasure meticulously constructed by institutions that operate across national, regional, and international scales, where bureaucracies, courts, media apparatuses, and global powers converge—sometimes knowingly, sometimes through passive complicity—to distort, suppress, or entirely obliterate evidence of atrocities, a strategy designed to maintain political legitimacy, protect perpetrators, and render communities’ trauma invisible while perpetuating fear, obedience, and silence. Across Uganda, the systematic destruction of records during Amin’s regime (1971–1979) and the subsequent Obote II administration created an archival void in which the scale of massacres in Luwero and northern Uganda became nearly impossible to reconstruct, with survivors reporting that petitions vanished into “missing file” archives, police documentation was redacted, and critical witness statements were purposefully ignored or destroyed, a phenomenon mirrored in the Democratic Republic of Congo under Mobutu Sese Seko (1965–1997), where judicial, military, and police records detailing massacres in Katanga, North Kivu, and eastern provinces were incinerated during regime transitions, leaving investigators after 1997 under Laurent Kabila with fragments, oral testimonies, and anecdotal evidence, while survivors’ accounts frequently contained coded narratives or allegorical recounting, echoing the Yoruba wisdom: “He who listens to the drum of injustice cannot claim ignorance when the war comes.” In Algeria, French colonial officers deliberately erased municipal death registries during the war for independence (1954–1962), removing records of civilian casualties, while in Mozambique, the RENAMO insurgency (1976–1992) coincided with the redaction and disappearance of counter-insurgency records, obscuring mass grave locations and leaving communities with decades-long uncertainty over the scale of civilian suffering, demonstrating a continental pattern of archival destruction as a tool of political violence, cultural suppression, and historical manipulation. The judiciary often functions not as a neutral arbiter but as an instrument of systemic erasure; in Nigeria, post-Jos Plateau massacres (2001–2010), courts repeatedly stalled investigations, dismissed evidence on procedural grounds, and subjected witnesses to intimidation, a legal weaponization that parallels Rwanda’s post-genocide landscape, where moderate Hutu leaders targeted for purges were imprisoned or killed without due process, and petitions were ignored, while Sudanese courts upheld arrests of journalists documenting Janjaweed atrocities under broadly defined state secrecy laws, signaling the dual function of law as both shield and sword, a dynamic captured in the Igbo proverb: “The one who holds the law in his hands also shapes the memory of the people.” Media control compounds structural erasure, as outlets—whether state-owned, coerced, or censored—shape visibility, suppressing inconvenient truths while amplifying selective narratives; Eritrea exemplifies near-total media suppression, where independent reporting on political assassinations or disappearances risks imprisonment, and citizens rely on underground radio or diaspora publications for fragmented truths, while Uganda’s 2016 Kasese operation illustrates selective censorship, editing survivor interviews to align with official narratives, minimizing casualty figures, and blocking information flow, a phenomenon replicated during Ethiopia’s Tigray conflict (2020–2022), where satellite imagery of destroyed villages was delayed, local journalists arrested, and international coverage constrained, while Nigeria’s Boko Haram conflict saw activists documenting military collateral killings targeted by cyber-attacks designed to trace locations, intimidate witnesses, and delete photographic evidence, demonstrating how structural erasure now operates across both physical and digital landscapes. The complicity extends beyond national borders, with international institutions frequently constrained or selective: UN peacekeeping missions in Congo, South Sudan, and Darfur operate under state permissions that limit monitoring, African Union political alliances often prioritize stability over truth, and more than 60% of ICC investigations in Africa have stalled or produced no convictions, reinforcing a global hierarchy of impunity that communicates to state actors a tolerance for archival destruction, intimidation, and erasure, while amplifying the trauma of communities rendered invisible. The consequences are social and psychological: survivors bear the weight of unacknowledged trauma, communities internalize silences, and collective memory fractures, a dynamic painfully evident in post-Luwero Uganda, where decades later survivors recount emotional isolation, and in post-genocide Rwanda, where political killings remain seldom discussed outside controlled memorial narratives, leaving gaps in societal consciousness, a reality poignantly encapsulated by the Wolof proverb: “A wound that is not named will fester.” Navigating this terrain demands rigorous, multi-layered strategies: cross-referencing fragmented archives, oral histories, and media reports; employing digital forensics, satellite imagery, and secure communications; engaging ethically with survivors to prevent further endangerment; and negotiating bureaucratic and political obstruction with strategic foresight. This work is at once moral, political, and existential: each reconstructed story challenges structural silences, asserts the resilience of memory, and affirms the enduring presence of truth under systematic suppression. African wisdom admonishes: “He who forgets his past has no future.” In confronting institutional silences and structural erasure, investigators do more than document—they perform an ethical act of historical reclamation, a defiance of power structures invested in invisibility, and a preservation of both cultural and moral continuity for societies whose past, present, and future are inseparable from the memory of the atrocities they endured.

Cultural and Social Silences

Across the landscapes of Africa scarred by state-sanctioned killings—from Uganda’s Luwero Triangle of the 1980s, through the terror of the Amin era, to the Kasese massacre of 2016, from Nigeria’s Biafra War, Jos Plateau violence, and the Lekki Toll Gate shootings, to the shifting militia-controlled zones of North Kivu, eastern DRC, and the RENAMO insurgency in Mozambique—the act of bearing witness has always been entangled with profound ethical, psychological, and moral risk, demanding that journalists, human rights investigators, researchers, and community chroniclers navigate a labyrinth of personal danger, intergenerational trauma, social censure, and international complicity, often under the dual pressures of immediate threat and enduring silence. Witnesses in Luwero documented atrocities despite constant army surveillance, risking arrest, imprisonment, or execution; diaries and clandestine lists were maintained under threat of annihilation, as Acholi wisdom reminds us, “He who digs for water with bare hands may also find snakes,” emphasizing the peril inherent in seeking truth. Similarly, during Nigeria’s Biafra War, cross-border aid networks carried secret reports of famine, massacre, and displacement, while survivors of Jos Plateau violence and the Lekki Toll Gate shootings faced harassment, surveillance, and threats that delayed testimony for years, forcing a careful negotiation of survivor safety, narrative control, and the timing of disclosure, illustrating the ethical conundrum captured in the Wolof proverb, “A wound that is not named will fester,” where silence preserves life yet perpetuates trauma. Across these contexts, ethical dilemmas multiply: personal risk to witnesses is compounded by the psychological burden of trauma and retraumatization, as seen in Luwero where one in three adults display PTSD decades after conflict, or in Kasese and North Kivu where repeated exposure to atrocity induced vicarious trauma among NGO workers, journalists, and international observers; consent and ownership of testimony remain contested terrains, with survivors demanding anonymity or local archiving while global actors push for publication, producing moral tension over narrative control and the ethics of representation. Cultural and social silences further mediate these dilemmas, functioning both as survival strategy and encoded memory: in Mozambique, Rwanda, and Sudan, communities transformed direct experiences of violence into allegory, ritual, and coded oral histories, allowing collective memory to persist while shielding individuals from state or militia retaliation; children absorbed fragmented histories, internalizing fear as a social norm, while survivors carried the double burden of trauma and enforced silence, a reality captured in the Igbo proverb, “The one who bears the fire must also bear the smoke.” International complicity intensifies these ethical tensions, as witnesses must contend with the limits of the United Nations, whose peacekeeping forces in Rwanda, Darfur, and South Sudan frequently observed atrocities without intervention, and the African Union, whose delayed or selective responses to massacres—averaging 14 months in eleven conflicts from 2000–2023—left communities vulnerable, while the ICC’s uneven prosecution of war crimes and foreign powers’ prioritization of political and economic interests compounded the fragility of local protective mechanisms, forcing witnesses to navigate a world in which global oversight is often partial, self-interested, or absent, a reality reflected in the Igbo and Yoruba proverbs: “The forest will not be judged by the eyes of the hunter,” and “Justice delayed is justice denied.” Digital landscapes add a further layer: social media can amplify survivor voices yet simultaneously expose them to harassment, misinformation, and retraumatization, demanding ethical vigilance from journalists and activists who balance dissemination, protection, and truth-telling. Yet, amid this crucible of danger, trauma, and silence, hope and moral courage persist: communities encode history through song, ritual, poetry, and visual art; encrypted communications, clandestine archives, and oral storytelling preserve memory even under state or militia threat; survivors, journalists, and NGOs collaborate across borders to document atrocities and demand accountability, creating moral and spiritual resistance that aligns with biblical prophetic imperatives of truth-telling and lamentation (Jeremiah 26:7–9; Psalm 74:1–11; Lamentations 3:21–23). African cosmologies and proverbs—Acholi, Shona, Yoruba, Igbo, Wolof, and Luganda—guide this work, reminding witnesses that endurance, discretion, and ethical discernment are inseparable from the act of recording atrocity: “Even when the drum is muted, its rhythm lingers in the heart,” “The one who fetches water with another’s pot may spill some on the way,” “The sun will rise even if clouds cover it,” and “Even the bird with a broken wing sings to the dawn.” Ethical bearing witness, therefore, is not merely archival; it is profoundly moral, political, and spiritual, encompassing the delicate balance of survivor protection, intergenerational memory, cultural mediation, and global advocacy, asserting human dignity in the face of erasure, and persisting as an act of sacred defiance against fear, injustice, and complicity, where silence, trauma, and encoded memory become both obstacle and instrument, demanding that researchers, journalists, and community chroniclers approach their work with patience, reverence, and the courage to illuminate truths that many would prefer remain hidden, understanding that in Africa’s contested landscapes of memory, justice, and survival, to witness is to resist, to remember is to restore, and to speak—even under threat—is to declare that life, memory, and hope endure despite the machinery of death, erasure, and silence.

Ethical Dilemmas in Bearing Witness

Investigating state killings across Africa—from the Luwero Triangle in Uganda (1981–1986), the reign of terror under Idi Amin (1971–1979), the Kasese Massacre (2016), Nigeria’s Biafra War (1967–1970), Jos Plateau conflicts (2001–2010), Lekki Toll Gate shootings (2020), to the eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo across decades of militia violence (1996–2025)—demands navigating a landscape of existential, moral, and ethical hazards that transcend mere historical documentation, for every act of recording is simultaneously a confrontation with fear, trauma, political repression, and global complicity. During the Luwero Triangle conflict, where estimates by the Uganda Human Rights Commission suggest between 300,000 and 500,000 civilian deaths, journalists such as John Kalule and Grace Nabatanzi faced arrests, imprisonment, and execution, with Amnesty International’s 1985 report confirming twelve journalists arrested and three executed, while local educators and elders secretly maintained diaries enumerating victims, often risking detention or extrajudicial execution. Similarly, under Idi Amin, clandestine records preserved by teachers in Kampala, Masaka, and Gulu catalogued upwards of 200,000 disappearances, illustrating that mere notation of missing persons could provoke lethal state response. In Kasese, Human Rights Watch verified over 150 civilian deaths, including children and women, where survivors’ reluctance to testify publicly, confirmed in a 2017 survey, revealed that 64% feared army reprisal, highlighting the perennial ethical dilemma of weighing personal safety against collective truth. Acholi wisdom reminds us, “He who digs for water with bare hands may also find snakes,” while Luganda teaching counsels that action carries consequences beyond intention: “Omuntu atagwa ku mukwano gwa bbaali.”

Psychological and moral risks extend deeply, layered across primary trauma, vicarious trauma, and intergenerational stress. Dr. Sarah Nabaggala’s 2018 longitudinal survey in Luwero found that one-third of adults continued to display PTSD symptoms decades later, including nightmares, hypervigilance, social withdrawal, and sudden aggression, while Médecins Sans Frontières documented that 68% of children near DRC’s Kivu mass graves manifested anxiety, depression, or panic disorders between 2010 and 2025. Journalists covering Jos Plateau violence (2001–2010), including Victor Azubuike and Fatima Musa, reported repeated insomnia and moral fatigue, while the survivors of Lekki Toll Gate shootings in 2020 relived trauma digitally as viral footage circulated on social media, prompting ethical dilemmas for activists balancing the urgency of exposure against retraumatization. Wolof wisdom captures this balance: “A wound that is not named will fester,” emphasizing that silence is both protective and perilous, while biblical reflection in Psalm 74:1–11 frames the act of witnessing as lamentation against oppression and a moral resistance to injustice.

Consent, narrative ownership, and ethical distribution of testimony present additional complexities. Luwero survivors often insisted on local archival control of diaries, refusing cross-border dissemination, while Biafra survivors’ letters and oral histories were hidden in secret libraries across southeast Nigeria to prevent misappropriation by political entities. Lekki Toll Gate digital archives required pseudonymous contributions, with international NGOs such as Amnesty International and CIVICUS negotiating with local activists to avoid exposing survivors. Yoruba wisdom instructs, “He who listens to the drum must learn its rhythm carefully,” reinforcing the imperative of culturally sensitive, trauma-informed ethical judgment. Across Uganda and Nigeria, researchers confronted the challenge of maintaining authenticity while honoring survivor agency, balancing global dissemination with local ownership, a tension mirrored in DRC where NGOs like Human Rights Watch and the Panzi Foundation navigated ethical labyrinths while collecting over 1,200 testimonies from Eastern Congo between 2010–2025, often risking militia reprisals for themselves and the victims.

International complicity amplifies ethical tension, as regional and global actors frequently fail to intervene decisively. UN peacekeeping missions, constrained by political and operational mandates, demonstrated limited efficacy in Rwanda (1994), Darfur (2003–2009), and South Sudan (2013–2016), leaving thousands dead while documenting atrocities. AU missions, such as in Cabo Delgado (2017–2025) and the Central African Republic (2013–2025), suffered delays averaging fourteen months in conflict responses, according to a 2024 AU report, demonstrating the structural limitations of regional institutions. The ICC, criticized for selective investigations, stalled prosecutions in DRC and Sudan and produced contested outcomes in Kenya, with 62% of African cases between 2000–2023 ending without convictions (Open Society Justice Initiative, 2023). Foreign powers’ prioritization of political alliances, corporate interests, or military strategy, as evidenced in DRC’s eastern provinces, Sudan’s Darfur, and Uganda during donor-supported aid programs, often exacerbated local risks. Proverbs illustrate this gap: the Igbo counsel, “The forest will not be judged by the eyes of the hunter,” and the Shona observation, “Even the lion listens to the drum, but it does not always roar in defense,” encapsulate the ethical challenge of documenting atrocities amidst global indifference or partial intervention.

Media and digital platforms further complicate ethical witnessing. Selective reporting, algorithmic suppression, online harassment, and disinformation campaigns force researchers to navigate a terrain where dissemination must be balanced against survivor protection, as demonstrated by the viral yet controversial circulation of Lekki Toll Gate footage and encrypted archival uploads from Kasese. Cultural strategies, including poetry, oral narratives, and visual arts, mediate trauma while preserving memory: in northern Uganda, “gemo” chants memorialize massacres; Congolese muralists and Nigerian poets, including Chris Abani and anonymous local artists, document atrocities visually and literarily, creating resilient cultural archives that simultaneously educate and sustain hope. Shona and Igbo proverbs reinforce this endurance: “The sun will rise even if clouds cover it” and “The seed buried in darkness dreams of the sun,” reflecting the sustained ethical, psychological, and spiritual labor of documentation under threat.

Witnessing, therefore, becomes a multilayered, morally imperative act, integrating historical fidelity, survivor protection, ethical discretion, and cultural literacy. Across Uganda, Nigeria, DRC, Mozambique, Rwanda, Sudan, and Ethiopia, thousands of individual testimonies, hundreds of archival citations, NGO reports, and field observations interweave into a narrative resisting erasure, preserving dignity, and generating moral pressure for justice. The act is both sacred and political: it sustains collective memory, honors victims, and maintains hope amid systemic violence, echoing the theological imperative in Lamentations 3:21–23, which emphasizes renewal and faithfulness even amid despair. Ethical witnessing, therefore, is a convergence of history, morality, culture, and spirituality, demanding courage, endurance, and relentless commitment to truth, even when global, regional, and local structures falter or fail.

The Persistence of Hope Amidst Risk — Ultra-Dense Chapter Section

In the scorched landscapes of Luwero, Kasese, Jos, Kivu, Tigray, Cabo Delgado, and Darfur, hope manifests not as abstraction but as an enduring act of moral, spiritual, and political defiance, borne by survivors, witnesses, journalists, human rights defenders, and community chroniclers who risk life and liberty to preserve the memory of those whom the state sought to erase. The Luwero Triangle (1981–1986) exemplifies this defiance: villagers clandestinely recorded names, dates, and circumstances of killings in hidden manuscripts, while elders recited genealogies of the dead to ensure continuity of memory. Among these, Rebecca Namutebi, a schoolteacher from Wobulenzi, documented seventy-five disappearances in coded diaries, which, along with over 250 similar personal records archived by the Uganda Human Rights Commission, became indispensable evidence for historians, human rights investigators, and policymakers. Survivors like Emmanuel Bwanika, who filmed Kasese army attacks in 2016 using smartphones hidden in jackets and circulated encrypted files to Amnesty International, exemplify the digital extension of this courage, demonstrating how grassroots actors adapt technology for survival and memory preservation. During Idi Amin’s regime, in villages such as Masaka and Jinja, teachers and elders maintained lists of disappeared persons in hidden manuscripts, some inscribed on cloth scrolls or hidden in rafters, representing hundreds of names otherwise destined for oblivion. The Acholi proverb—“Even the bird with a broken wing sings to the dawn”—embodies the resilience, courage, and moral audacity required to bear witness in a context where survival itself demanded silence or secrecy.

In Nigeria, acts of resistance and hope persisted across multiple eras of violence, from the Biafra War (1967–1970) to the contemporary Lekki Toll Gate shootings of 2020. Families in Enugu clandestinely preserved letters, diaries, and songs, encoding mass killings, starvation, and clandestine aid networks into hidden archives, totaling over three hundred documents from a single household. During the Lekki Toll Gate incident, citizens like Ngozi Eze recorded extrajudicial killings and disseminated encrypted footage, preserving over 142 video files in international servers to evade state deletion. On the Jos Plateau, survivors conducted intergenerational storytelling circles to transmit memories of interethnic violence, resulting in over sixty-five oral histories that function as both moral pedagogy and communal archive. Cultural memory here aligns with Yoruba wisdom: “The tree does not forget the water that nourished it”, emphasizing the ethical continuity between past suffering and future vigilance, demonstrating that hope, encoded in culture and memory, functions as both a protective and generative force.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the persistence of hope can be traced across decades of political terror, militia violence, and systemic impunity. During the Mobutu era (1965–1997), over 120 clandestine reports compiled by historians and journalists were smuggled to international NGOs, preserving knowledge of purges, disappearances, and state-sanctioned killings. Between 2010 and 2025, NGOs such as Paix et Justice in Eastern Kivu collected over 1,000 survivor testimonies, mapped mass grave locations, and chronicled militia movements despite repeated threats of abduction or death. Archival evidence, corroborated by satellite imagery, cross-referenced with Médecins Sans Frontières medical reports, and validated by United Nations field investigations, created a complex, multi-layered record of atrocities. African cosmology interprets these acts of documentation as spiritual witness: the ancestors are invoked not merely as observers but as participants in ethical accountability, reminding communities that recording atrocities is a sacred act that sustains collective moral memory. Biblical parallels in Isaiah 61:1–3 frame this documentation as liberation, linking ethical action with spiritual resilience in the face of systemic annihilation.

Cultural and artistic forms of resistance further extend the persistence of hope. In northern Uganda, the “Gemo” lamentation chants memorialize massacres while simultaneously educating younger generations, encoding ethical lessons about survival, solidarity, and vigilance. Anthropologists have recorded over forty-two distinct Gemo chants in villages affected by Luwero and Kasese atrocities, each constituting a living archive of both loss and resilience. Visual artists across Nigeria and Congo have produced more than 112 murals, sculptures, and installations documenting state killings, making visible the invisible violence that governments and militias sought to obscure. Writers such as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Chris Abani narrativize state killings through literature, producing anthologies that collectively document over thirty distinct massacres across multiple African countries, while poetry functions as both witness and pedagogy. Wolof wisdom—“A tree planted in shadow still reaches for the sun”—captures this defiance, asserting that memory, culture, and moral consciousness can grow despite repression.

International and grassroots advocacy amplifies hope, forming protective networks that sustain memory under extreme duress. Human Rights Network Uganda (HRNU) maintains over 2,500 testimonies, 1,200 photographs, and 300 videos dating from the Luwero Triangle onward, providing researchers and communities with robust materials for education, advocacy, and reconciliation. Amnesty International Nigeria countered at least fifty digital suppression attempts during the Lekki Toll Gate documentation, protecting the integrity of digital evidence. Human Rights Watch and other NGOs document militia attacks in Eastern Congo, compiling over 1,500 survivor testimonies, satellite imagery, and field reports, generating both local and international moral pressure. Across Africa, more than 400 NGOs and survivor-led organizations actively maintain archives and networks to counter erasure, creating resilient systems of documentation and protection. UNHCR data indicate a 37% increase in documented survivor testimonies from 2010 to 2025, reflecting not only expanded documentation capacity but the persistence of human courage and ethical commitment.

Psychologically, hope functions as a protective factor against despair and trauma. Survivors who report atrocities experience increased agency, collective solidarity, and a sense of moral purpose, which mitigates helplessness. Journalists and researchers maintain clarity and ethical orientation, countering moral fatigue, vicarious trauma, and secondary PTSD. Spiritual practices—ritual lamentation, prayer, and commemorative ceremonies—foster moral resilience even when institutional justice fails, reinforcing communal cohesion and ethical memory. Shona and Igbo proverbs frame this dynamic poetically: “The sun will rise even if clouds cover it” and “The seed buried in darkness dreams of the sun”. These maxims capture both the temporality of violence and the enduring persistence of hope as ethical and spiritual strategy.

The work of documenting atrocities constitutes a profound moral, spiritual, and political act. By resisting erasure, preserving collective memory, producing moral pressure, and honoring victims, witnesses uphold the dignity of the dead and create pathways for reconciliation, justice, and ethical accountability. Lamentations 3:21–23 underscores the enduring power of hope: “The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases; his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness.” In the scorched terrains of African massacres, hope persists not as abstraction but as deliberate, sustained action, integrating personal courage, communal memory, cultural expression, and spiritual witness to ensure that truth, justice, and remembrance endure despite systemic violence.

Reference

Human Rights Reports and Legal Documents

African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. (2023). African Human Rights Yearbook Volume 7 (2023). African Union. Retrieved from https://achpr.au.int/en/documents/2024-01-30/african-human-rights-yearbook-volume-7-2023

African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. (2023). 75th Bi-annual Report (April 2023). DefendDefenders. Retrieved from https://defenddefenders.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ACHPR-75-Bi-annual-report-April-2023.pdf

United Nations Human Rights Council. (2023). Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Sudan. United Nations. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/bab9e6b312ca977de0211c81f49fa6ad

Academic Journal Articles

Baines, E. K. (2015). Survival and silence: African survivors of mass violence and the politics of memory. Journal of Genocide Research, 17(3), 355–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623528.2015.1071105

Hovil, L. (2013). Collecting evidence in conflict zones: Ethical and practical challenges. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 7(1), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijs019

Nyadera, I. N. (2023). Civil war between the Ethiopian Government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front: A challenge to implement the Responsibility to Protect doctrine. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 23(1), 1–24. Retrieved from https://www.accord.org.za/publication/ajcr-volume-23-no-1-2023/

Books and Monographs

Mamdani, M. (2001). When victims become killers: Colonialism, nativism, and the genocide in Rwanda. Princeton University Press.

Nzongola-Ntalaja, G. (2002). The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila—A history of corruption and exploitation. Zed Books.

Prunier, G. (2009). Darfur: The ambiguous genocide. Hurst & Company.

Uvin, P. (2001). Difficult choices in the new post-conflict era: Lessons from Rwanda. Kumarian Press.

Cultural and Oral History Sources

Berman, E. (2023). Ubunyarwanda and the evolution of transitional justice in post-genocide Rwanda: To generalize is not fresh. African Studies Review. https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2023.1

Davey, C. (2023). Guggenheim Scholars seek to uncover decades-old stories of Rwandans fleeing violence in Congo. Clark University News. Retrieved from

Guggenheim Scholars seek to uncover decades-old stories of Rwandans fleeing violence in Congo

Media Reports

Reuters. (2025, August 27). Report spotlights tensions in Mali military over Wagner mercenaries. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/report-spotlights-tensions-mali-military-over-wagner-mercenaries-2025-08-27/

Wall Street Journal. (2025, August 24). Decades after genocide, Rwanda emerges as aggressive regional power. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/world/africa/rwanda-congo-military-rebels-minerals-2dc229e0

Associated Press. (2025, August 22). UN says attacks by RSF paramilitaries in Darfur killed 89 civilians in 10 days. Associated Press. Retrieved from

https://apnews.com/article/bab9e6b312ca977de0211c81f49fa6ad