By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Introduction

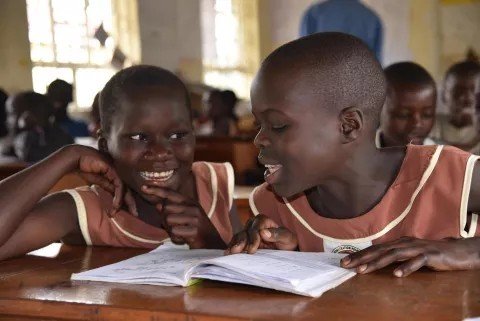

Education is not merely a social service; it is the foundation of personal dignity, societal resilience, and national development. In Uganda, the promise of education is unevenly distributed, revealing persistent gender disparities that limit the potential of millions of young women. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS, 2024), while overall literacy rates have improved over the past two decades, significant gaps remain between boys and girls, particularly in rural and historically marginalized districts. This disparity is not only a moral issue but a structural constraint on development. In a nation where over 75% of the population is under the age of 30, the exclusion of girls from full educational participation threatens to deprive the country of half its human capital, weakening social cohesion, economic productivity, and political engagement. The challenge is therefore not merely to enroll girls in school but to ensure their retention, progression, and empowerment, a task that requires comprehensive interventions across cultural, economic, and policy dimensions.

Current Status of Girls’ Education in Uganda

Enrollment and Retention

The most recent UBOS census and thematic reports highlight a mixed picture. Primary enrollment is near universal in urban centers, but disparities persist in rural areas, where nearly 26% of primary-age girls remain out of school (UBOS, 2024). By lower secondary, the dropout rate among girls rises sharply to over 30%, reflecting both social and structural barriers. These numbers underscore that enrollment statistics alone do not capture the full extent of educational inequity: attending school for a few years is insufficient if the quality of learning is poor, if progression is interrupted by pregnancy or marriage, or if the schooling environment is unsafe. In districts such as Karamoja, Bukedi, and parts of Busoga, poor infrastructure, teacher shortages, and long distances to schools combine with cultural expectations to push girls out of classrooms. These realities reveal that the challenge is not simply numerical but systemic, demanding solutions that address both access and the conditions under which girls can thrive in school.

Teenage Pregnancy and Early Marriage

Teenage pregnancy remains a principal driver of school dropout among girls. UNFPA and UNICEF data indicate that roughly 25% of Ugandan teenage girls become pregnant by age 19, a figure that is highest in rural and northern districts where poverty and limited access to reproductive health services converge (UNICEF, 2025; UNFPA, 2021). Child marriage compounds this problem: 34% of women in Uganda were married before age 18, a practice that truncates educational opportunities and perpetuates cycles of poverty. These social realities are closely intertwined; early pregnancy often leads to early marriage, which in turn eliminates the possibility of continued education. The impacts are generational, affecting not only the girls themselves but also their children, perpetuating inequality in education, health, and economic opportunity. Policy interventions must therefore address both reproductive health and social norms simultaneously, creating pathways for girls to return to school after childbirth or to delay marriage altogether.

Socio-Cultural and Economic Barriers

Cultural expectations continue to undervalue girls’ education in significant portions of Uganda. Traditional norms often position girls primarily as future wives and mothers, limiting the perceived utility of their education. Parents may prioritize boys’ schooling because boys are expected to contribute economically to the household in the long term, whereas girls’ labor is often diverted toward domestic tasks such as fetching water, cooking, and childcare. Economic constraints exacerbate these challenges: school fees, uniforms, books, and transport costs absorb significant household resources, leading families to make difficult choices about which children to educate. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed and intensified these vulnerabilities: school closures increased teenage pregnancies and child marriages, and over 30,000 schoolgirls were reported to have become pregnant during lockdown periods (UNFPA, 2021). These statistics reveal that addressing economic and social barriers is critical to ensuring girls’ uninterrupted participation in education.

Regional Disparities

Uganda’s regional differences in girls’ education are stark. Northern and Eastern subregions — including Karamoja, Bukedi, and Busoga — consistently show the lowest enrollment and highest dropout rates. These areas are often characterized by historical marginalization, conflict, underdeveloped infrastructure, and concentrated poverty. UBOS data shows that in some districts, over 35% of girls of secondary-school age are not in school, compared to less than 20% in more developed regions such as Kigezi or Ankole. This uneven distribution highlights the importance of place-sensitive policies: interventions must consider local realities such as transportation challenges, teacher distribution, and cultural expectations, rather than relying solely on national averages, which can mask pockets of severe exclusion. Regional disparities also illustrate the need for equitable resource allocation and sustained investment in rural and marginalized areas to bridge the gender gap effectively.

Economic, Health, and Social Impacts

The consequences of excluding girls from education are profound and multi-dimensional. Economically, educated women are more likely to participate in the labor force, earn higher incomes, and contribute to the growth and diversification of the national economy. Studies show that each additional year of schooling for a girl can increase her lifetime earnings by 10–20% (Psacharopoulos & Patrinos, 2018). Health outcomes are similarly affected: educated women tend to have fewer children, spaced more safely, and are more likely to access healthcare services for themselves and their families. Socially and politically, education empowers women to engage in decision-making processes at local and national levels, fostering gender equality and democratic governance. In a country like Uganda, where the total fertility rate remains high at 5.2 births per woman (World Bank, 2024), the transformative potential of girls’ education is particularly pronounced, with benefits that extend across generations and entire communities.

Strategies to Bridge the Gap

Closing the gender gap in education requires a multi-layered approach. Policy interventions such as Universal Primary Education (UPE) and Universal Secondary Education (USE) provide a foundation, but they must be supplemented by targeted conditional and unconditional transfers to alleviate the economic burden on families. Community engagement is equally critical: programs that involve parents, local leaders, and religious institutions have demonstrated effectiveness in shifting harmful norms and promoting girls’ continued enrollment. Schools must also become more gender-sensitive, providing menstrual hygiene management, safe sanitation facilities, and supportive environments that enable adolescent girls to attend consistently. Expanding vocational and technical pathways (BTVET) can provide alternative routes for girls who may face barriers to traditional academic progression, creating credible opportunities for economic participation and empowerment. Data systems must be strengthened to monitor progress and inform adaptive policy interventions, ensuring that gains in gender parity are measurable, sustainable, and equitable.

Conclusion

Bridging the gender gap in education is both an ethical imperative and a strategic necessity for Uganda. Current data demonstrates that despite progress in enrollment and literacy, substantial barriers remain in retention, progression, and quality of education for girls. Persistent challenges — from early marriage and teenage pregnancy to economic constraints and cultural norms — require comprehensive and sustained solutions. By investing in girls’ education, Uganda can harness the full potential of its population, promote intergenerational equity, and accelerate national development. Education for girls is not merely a right; it is a foundation for prosperity, stability, and dignity across the nation.

References

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). (2024). National Population and Housing Census 2024: Final Report. Kampala: UBOS. Retrieved from https://www.ubos.org

UNICEF Uganda. (2025). Teenage Pregnancy in Uganda. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/uganda/topics/teenage-pregnancy

UNICEF. (2025). Child Marriage in Uganda. Retrieved from https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/learning-resources/child-marriage-atlas/atlas/uganda/

World Bank. (2024). Fertility Rate, Total (Births per Woman) – Uganda. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=UG

Psacharopoulos, G., & Patrinos, H. (2018). Returns to investment in education: A decennial review of the global literature. Education Economics, 26(5), 445–458.

UNFPA. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on teenage pregnancies and child marriages in Uganda. Kampala: UNFPA Uganda.