By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Emkaijawrites@gmail.com

“When the lion lays down its roar,

the earth remembers the song of the dove.”

— Igbo Proverb

Introduction

The Soil of Strife: Africa’s Long Night of Rebelism

From the emerald hills of Rwanda to the scorched deserts of Mali, from the mineral-rich veins of the Congo to the forgotten corners of the Central African Republic, rebelism has left its haunting footprints across the body of Africa. It is a wound that suppurates beneath the surface of our national identities, a prolonged groan echoing from the blood-stained soils where hope is often buried beneath the boots of young boys turned child soldiers, prophets turned rebels, and revolutions turned syndicates of terror. The African continent, as of 2025, is home to more than 70 active rebel groups across 22 countries, from Islamist insurgencies to secessionist movements, ethnic militias, and warlord armies. These are not isolated phenomena but symptoms of a deeper ailment—a collapse of covenant, meaning, memory, and moral imagination.

Yet rebelism is not merely a political reality. It is a theological and existential crisis. In many African nations, rebels are not simply men with guns but failed citizens, neglected children, disillusioned prophets, and sometimes even victims of a broken social contract. They are birthed from abandoned education systems, crippled economies, stolen elections, state violence, and the silent complicity of religious institutions. In Nigeria, where Boko Haram continues its reign of fear, over 2.9 million people have been internally displaced. In eastern Congo, the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) have left over 6,000 civilians dead in recent years. The battlefield is no longer just a distant jungle—it is the classroom, the pulpit, the village, and the womb.

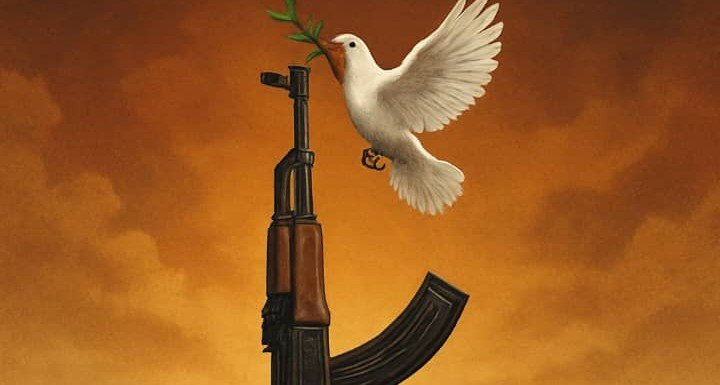

The Bible is not silent on rebellion. From the fall of Lucifer to the uprisings of Korah, from Absalom’s coup against David to the revolutionary zealots of Christ’s time, scripture presents rebelism not merely as a political act but a deeply spiritual disorder. And yet, the biblical narrative also speaks of resistance to unjust powers, from Moses confronting Pharaoh to the Hebrew midwives defying genocidal decrees. The line between holy resistance and destructive rebellion must be carefully drawn. The challenge for Africa today is not only to end violent rebel movements, but to discern when the cry of resistance is righteous, and when it has become a cancer. This essay takes a multidisciplinary pilgrimage—traversing scripture, political history, sociology, and African wisdom—to explore the roots of rebelism and propose biblically grounded, contextually intelligent, and spiritually faithful paths to peace.

I. Section 2: Historical Roots of Rebelism in Africa — Memory, Wounds, and Misgovernance

Colonial Disruption and Birth of Rebellion

Rebelism in Africa did not sprout in a vacuum. Its seedbed is tangled in the long, bleeding roots of colonial domination, where artificial borders carved by foreign hands disregarded tribal realities and spiritual geographies. The Berlin Conference of 1884–85 remains one of the bloodiest blueprints ever penned without a drop of ink touching African soil. Across the continent, rebellion was often the initial voice of liberation, echoing in the Mau Mau uprising of Kenya (1952–1960), the Algerian war of independence (1954–1962), and the anti-Portuguese revolts in Angola and Mozambique. But with independence came disappointment, as many freedom fighters morphed into autocrats, and rebels merely changed uniforms. In these early decades, over 27 major insurgencies erupted across post-independence Africa, each one narrating an unfinished freedom, each one a cry against betrayal.

Betrayals of Nationhood and the Rise of Warlords

The postcolonial state, far from being a sanctuary, became a battlefield of broken promises. The vacuum left by colonial rule was quickly filled with clientelism, tribalism, and cold-blooded greed. From Charles Taylor’s merciless grip on Liberia to Joseph Kony’s chilling campaign across northern Uganda and into the heartlands of the DRC, rebel movements began to mutate. No longer mere voices of resistance, many became parasites feeding off state fragility. Between 1990 and 2010 alone, over 20 African countries experienced armed insurgencies; in some cases, like Sudan, multiple rebel groups operated concurrently. According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, over 5.4 million lives were lost in the DRC alone due to conflict-related causes by 2008—a human catastrophe cloaked in political silence.

Foreign Meddling and the Business of War

Where there is chaos, vultures descend. Rebelism in Africa has often been a lucrative business underwritten by external interests. Multinational corporations, arms dealers, and shadowy foreign governments have financed proxy militias in exchange for access to diamonds, oil, and coltan. The UN Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources reported that over $1 billion worth of minerals are trafficked annually from conflict zones in eastern Congo, much of it funding armed groups. In Libya, the post-Gaddafi collapse turned the country into a weapons depot, with sophisticated arms flowing southward to fuel insurgencies from Mali to the Central African Republic. Behind many rebel flags fluttering in the wind is the scent of dollar bills soaked in blood.

Paragraph 4: Trauma, Orphaned Youth, and the Cycle of Vengeance

Behind the statistics lie stories of boys who never got to be boys, girls robbed of their lullabies, and entire villages erased like whispers in the wind. Rebelism has fed off trauma like a scavenger feeds on the dead. In northern Uganda, the Lord’s Resistance Army abducted over 60,000 children between 1987 and 2006, many forced to become soldiers or “wives” of commanders. The failure of demobilization programs across Africa has created a generation of disillusioned youth—orphans of both war and the state. According to UNICEF, over 270,000 children are currently associated with armed forces or groups globally, many in Africa. Without healing, without justice, and without a theology of restoration, the cycle of vengeance becomes a sacred script rewritten with every new generation.

Section 3: Interdisciplinary Reflections — The Political, Economic, and Cultural Fertilizers of Rebelism in Africa

Rebelism does not erupt from a vacuum; it germinates in the unhealed wounds of the body politic and is watered by droughts of justice, betrayal of governance, and the betrayal of ancestral promises. From a political science lens, most African rebel movements emerge in regions where governments have failed to deliver basic services, respect human rights, or ensure equitable representation. According to the World Bank, over 420 million Africans still live in fragile or conflict-affected areas, and 31 out of 54 African countries recorded armed insurgencies between 2000 and 2024. These rebellions often originate from grievances over land dispossession, marginalization of ethnic minorities, or the alienation of youth. The Lord warns in Proverbs 29:2, “When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice: but when the wicked beareth rule, the people mourn.” Rebelism is not always born out of rebellion—but out of mourning that is politicized, and silence that becomes fire.

Economically, rebelism thrives in the womb of poverty and underdevelopment. The African Development Bank reports that sub-Saharan Africa loses $100 billion annually due to conflict-related disruptions, with countries like the DRC, South Sudan, and Somalia bleeding the most. Unemployment, especially among youth—where rates surpass 60% in some regions—creates a fertile ground for rebel recruitment. A 2023 report by the Institute for Security Studies found that 87% of ex-combatants interviewed in the Sahel cited economic survival as their chief motivation for joining militant groups. Here, biblical economics becomes urgent: the Jubilee laws in Leviticus 25 speak of debt release, land restoration, and rest—a sacred blueprint Africa has ignored. When people are denied inheritance, they forge weapons from their hunger.

Culturally, the wounds of colonialism still echo. The psychological trauma of identity erasure, arbitrary borders, and cultural suppression has never been fully exorcised. Many rebel groups, such as the Tuareg in Mali or the Mbororo pastoralists in Cameroon, frame their struggles as wars for cultural survival. The disconnection from ancestral values, compounded by the erosion of communal life and traditional conflict-resolution systems, has left a void. And in that void, violence masquerades as justice. As an African proverb says, “If the rhythm of the drumbeat changes, the dance must also change.” But what happens when the drums are stolen, and the dancers silenced? Rebelism becomes the haunting song of a people asking to be remembered.

From an anthropological and media standpoint, rebel movements are also shaped by mythmaking and martyrdom. The lionizing of past revolutionaries—Lumumba, Sankara, Biko—has created a symbolic economy where rebellion is seen as the only path to agency. While some rebel groups are driven by greed or power, others emerge from genuine cries for justice. The danger lies in romanticizing violence or simplifying complex grievances into slogans. As Jesus reminded Peter in the garden, “Put away your sword. Those who live by the sword shall die by the sword” (Matthew 26:52). The sword may be lifted in desperation, but healing requires tools forged not for battle, but for building—pens, policies, ploughshares, and truth.

Section 4: The Role of Churches and Faith-Based Institutions in Ending Rebelism

In the African wild, where hyenas howl and vultures circle the wounded, the church has often stood as both a refuge and a battlefield. While many churches have offered sanctuary and moral clarity during seasons of political decay, others have been complicit—silenced by fear, bribed by power, or seduced by the mirage of prosperity gospels. In nations like the Central African Republic and South Sudan, where civil conflict has baptized entire generations in blood, religious leaders have mediated ceasefires, led peace caravans, and even laid down their lives for truth. In Uganda, Archbishop Janani Luwum remains an enduring martyr, slain under Idi Amin’s tyranny for opposing state-sanctioned violence. The moral authority of the Church, when not compromised, can be more potent than any political platform or rebel ideology. As Proverbs 29:18 reminds us, “Where there is no vision, the people perish,”—but when the pulpit speaks with prophetic fire, empires tremble.

Yet the failure of many churches to speak with bold clarity has worsened rebelism. In Congo, for instance, reports from Global Witness and Human Rights Watch document that some clerics have blessed warlords or accepted offerings tainted by conflict minerals. In Nigeria, churches in the northeast have been caught in the crossfire between Boko Haram insurgents and state forces, and many remain mute for survival. The silence becomes sinful. In Matthew 5:13, Jesus warns, “If the salt loses its flavor, how shall it be seasoned?” A church that does not confront the principalities of violence becomes a chaplain to chaos. Faith-based organizations must not only pray for peace; they must confront the social injustices and economic deprivations that fuel rebellion. According to a 2024 report by Afrobarometer, over 63% of citizens across 14 African countries believe religious leaders should engage in political accountability, not merely spiritual guidance.

Moreover, churches must move from charity to structural advocacy. Feeding the hungry rebel child without interrogating the militarized economy that manufactures orphans is a spiritual malpractice. Faith institutions must reclaim their public theology—one rooted in Isaiah’s vision of a peaceable kingdom, where swords are beaten into ploughshares and spears into pruning hooks (Isaiah 2:4). The Pan-African faith movement can organize theological summits, peace pilgrimages, and pastoral trainings in conflict zones. In Rwanda, after the 1994 genocide, churches like the Anglican Church led healing dialogues between victims and perpetrators through biblical reconciliation frameworks. We need more of this. We need churches that do not fear governments or armed militias, but fear God and love the people enough to stand between them.

Finally, the African proverb teaches us, “He who is not beaten by the sun is beaten by the dew”—a reminder that passivity invites destruction. Faith-based institutions must not wait until the fire consumes the altar. Instead, they must proactively cultivate peace, educate youth in the ethics of justice, and denounce every theology that glorifies vengeance. Across the continent, over 80% of the population identifies with a religion. That’s more than one billion souls. If just 10% of faith institutions implemented peace education curricula, trauma healing programs, and justice sermons, the spiritual climate of Africa would shift. The church must become the continent’s conscience again—not a spectator, but a prophetic participant in dismantling the roots of rebelism.

Section 5: Reclaiming the Prophetic Voice — The Role of the Church and Religious Institutions in Ending Rebelism

In times of moral collapse, when rebel groups rise like locusts from wounded soil, devouring nations and baptizing bullets in the names of justice, tribe, or survival, the Church must not be found asleep. The silence of the pulpit in the face of injustice is itself a betrayal of the Gospel. Scripture thunderously declares in Isaiah 58:1, “Cry aloud, do not hold back; lift up your voice like a trumpet; declare to my people their transgression.” Yet, in many regions, the Church in Africa has stood as a neutral observer, mouthing platitudes while warlords baptize children into cycles of vengeance. A reborn theology of resistance must arise — one that does not merely pray for peace, but boldly interrupts the machinery of violence with prophetic action, spiritual courage, and ethical clarity.

Indeed, the prophetic tradition in Scripture offers a fierce template for such engagement. Consider Amos, who thundered against corrupt rulers, or Jeremiah, who wept for a broken Jerusalem while denouncing false shepherds. The Church must retrieve its ancient calling not only as comforter of souls, but as midwife of justice. African theologian Kä Mana once lamented that much of African Christianity has been “domesticated by power,” losing its capacity to disturb the unjust order. Yet where were the churches when child soldiers were being recruited in the Democratic Republic of Congo, or when arms were being trafficked into Sudan under the cloak of tribal liberation? The blood cries out from the ground, and God still asks as He did in Genesis, “Where is your brother?”

A prophetic Church must become a peacemaker, not a passive observer. This means hosting peace dialogues, excommunicating war financiers, denouncing ethnic incitement, and offering sanctuary to displaced communities. In Nigeria, the Interfaith Mediation Centre in Kaduna has pioneered such initiatives, helping to defuse cycles of Christian-Muslim violence. Across Central Africa, theologians like Emmanuel Katongole and Jean-Marc Ela have reminded the continent that true religion weds lament with action. Even Jesus, the Prince of Peace, was not neutral: he overturned tables in the temple and rebuked rulers who crushed the poor. So too must our religious leaders speak truth to rebel power and government corruption alike, without fear or favor.

Finally, let the Church train her prophets and evangelists to understand the historical roots of conflict — colonial divides, poverty, exclusion, and generational trauma. Too often, pastors spiritualize wars that are born from structural sins. The fight against rebelism is not just about casting out devils but disarming ideologies and dismantling injustice. Seminaries must teach conflict transformation, political theology, and trauma healing alongside biblical exegesis. Only then will the Church regain its spine and its song — standing not as court chaplain to dictators or rebels, but as a burning bush in the wilderness, calling Africa’s warlords to repentance, and her people to peace.

Section 6: Policy, Peacebuilding, and Regional Governance — Crafting Structures That Heal

Peace is not merely the absence of war but the presence of justice, order, and flourishing communities—a vision deeply rooted in biblical wisdom where God establishes righteous governance as a foundation for peace (Proverbs 29:4). In Africa, fragmented state institutions and weak regional cooperation have allowed rebelism to fester. Between 2000 and 2024, over 420 violent conflicts erupted across the continent, many spilling over porous borders and undermining sovereignty (Uppsala Conflict Data Program). These conflicts are exacerbated by weak governance indices, with 33 African countries ranking in the bottom third globally for corruption, rule of law, and public trust (Transparency International, 2024). To break cycles of rebellion, there must be deliberate, transparent, and accountable governance.

The African Union (AU), with its Agenda 2063 and Peace and Security Council, represents a hopeful model for regional collaboration. Yet, funding gaps and political will undermine its potential. According to a 2023 AU report, only 24% of the Peace Fund budget was disbursed due to bureaucratic delays and member-state non-contributions. Strengthening AU’s mandate to mediate conflicts, enforce sanctions on war profiteers, and support peacekeeping missions is critical. Here, the biblical mandate of justice resonates deeply: “He who rules over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God” (2 Samuel 23:3). Governments and regional bodies must embrace servant leadership, prioritizing the vulnerable over elites, and peace over power.

Policy must also embrace community-centered peacebuilding. Evidence from Rwanda’s gacaca courts and Sierra Leone’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission shows the power of restorative justice rooted in indigenous practices. These structures provided forums for truth-telling, forgiveness, and reparations, allowing survivors and perpetrators to rebuild social fabric. Yet only 12 African countries have formally integrated such mechanisms into post-conflict recovery frameworks. Investment in trauma healing, youth empowerment, and land restitution is essential—areas often overlooked in peace accords. The Bible’s call to “restore the streets to dwell in” (Jeremiah 31:38) challenges policymakers to envision holistic reconstruction beyond ceasefire agreements.

Finally, sustainable peace requires addressing the economic drivers of rebelism. Conflict minerals, illicit arms trafficking, and criminal networks feed war economies generating over $1.5 billion annually in illegal profits across the Great Lakes region (UN Panel of Experts, 2024). Enhancing transparency, enacting anti-corruption laws, and supporting ethical trade partnerships can starve rebel groups of resources. Scripture reminds us in Micah 6:8 that God requires us “to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly.” When governments, civil society, and international partners embrace this covenantal ethic, the gates of rebellion will tremble before the rising dawn of peace.

Section 7: Youth Empowerment and Education — The Antidotes to Rebel Recruitment

Youth are the heartbeat of Africa, pulsing with potential and promise; yet they are also the most vulnerable to the siren call of rebel militias. With over 60% of Africa’s population under 25, and youth unemployment rates soaring above 30% continent-wide—reaching 65% in conflict-affected regions like the Sahel (International Labour Organization, 2024)—the fertile ground for recruitment is tragically vast. The biblical narrative mourns the loss of youth to violence; Jeremiah laments, “My eyes fail from weeping, I am in torment within; my heart is poured out on the ground because my people are destroyed.” (Lamentations 2:11). Education and empowerment must become the twin pillars lifting young Africans out of despair and away from the gun.

Formal education, however, is only part of the remedy. In many rebel-affected areas, schools are targets—over 600 schools attacked in Nigeria and Mali between 2015 and 2023, displacing hundreds of thousands of children (Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, 2023). To combat this, faith-based and community organizations have pioneered alternative education models—mobile schools, peace clubs, and trauma-informed pedagogy—that nurture resilience alongside literacy. Proverbs 22:6 counsels, “Train up a child in the way he should go; even when he is old he will not depart from it.” Such investments are spiritual and practical acts of rebellion against the cycle of violence.

Beyond education, youth empowerment must address economic marginalization. Programs offering vocational training, microfinance, and entrepreneurship have shown promising results. In Sierra Leone, a 2022 initiative trained over 15,000 youth in sustainable farming and crafts, reducing recruitment by armed groups by nearly 40% within two years. These interventions align with biblical justice, echoing the mandate to “speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves” (Proverbs 31:8). When young Africans see tangible futures not tied to violence but to creation and community, the lure of rebellion loses its grip.

Finally, youth voices must be central in peacebuilding and policy formulation. In South Sudan, the National Youth Forum has become a critical platform for dialogue, influencing ceasefire negotiations and community reconciliation efforts. The African proverb, “If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together,” reminds us that youth-led partnerships across ethnic, religious, and national divides carry the seeds of lasting peace. Empowered, educated, and engaged youth are not only the antidote to rebel recruitment but the architects of Africa’s hopeful tomorrow.

Section 8: Conclusion and Prophetic Call to Action

The story of rebelism in Africa is a tapestry woven with threads of pain, betrayal, resilience, and unfulfilled promise. Yet beneath the bloodstained fabric lies a sacred possibility: a continent where swords are hammered into ploughshares, and the dance of war is replaced by the song of peace. The biblical vision of Isaiah 2:4 calls us beyond conflict to a future where “nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.” This vision is not naïve but prophetic—a summons to moral courage, communal healing, and the radical restructuring of society. It demands that we confront rebelism not only as a political or security problem but as a spiritual and cultural wound that calls for holistic restoration.

Africa’s liberation from the cycle of rebellion requires the weaving together of multiple strands—robust governance, community healing, youth empowerment, economic justice, and the bold voice of the Church. Each actor—state, civil society, faith institutions, and youth—must enter this sacred covenant with humility and perseverance. The 70+ active rebel groups, the millions displaced, and the countless lives scarred by war demand that peace is not deferred or compromised but actively pursued with urgency. As the African proverb teaches, “When there is no enemy within, the enemy outside cannot hurt you.” True peace begins with the healing of internal divisions—within families, communities, and nations.

The prophetic and practical task before us is immense but not impossible. It calls us to a justice that remembers, a mercy that transforms, and a courage that does not flinch in the face of power. The church must reclaim its prophetic voice, the state must rise as servant-leader, and youth must be lifted from despair into dignity. Together, these forces can dismantle the scaffolding of rebelism and build a new architecture of peace grounded in biblical truth and African wisdom. For as Jeremiah reminds us, “I know the plans I have for you… to give you a future and a hope” (Jeremiah 29:11). Africa’s future waits—bright, bold, and redeemed.

Let this essay be a clarion call: to governments that govern justly, to churches that preach courageously, to communities that heal openly, and to young hearts that dream boldly. Let us forge ploughshares from swords and plant seeds of peace in the once-barren fields of rebellion. The road is long, the wounds deep, but the promise eternal. As Psalm 85:10 proclaims, “Mercy and truth have met together; righteousness and peace have kissed each other.” May this sacred embrace become Africa’s new song.

Bibliography

Books and Academic Sources

Brueggemann, Walter. Theology of the Old Testament: Testimony, Dispute, Advocacy. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1997.

Katongole, Emmanuel. The Sacrifice of Africa: A Political Theology for Africa. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2011.

Mamdani, Mahmood. When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton University Press, 2001.

Manning, Patrick. African Rebellion and Civil War: Challenges to Statehood. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Mkandawire, Thandika. African Intellectuals: Rethinking Politics, Language, Gender and Development. Zed Books, 2010.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. Coloniality of Power in Postcolonial Africa: Myths of Decolonization. Dakar: CODESRIA, 2013.

Sider, Ronald J. Just Politics: A Guide for Christian Engagement. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2014.

Reports and Data Sources

African Development Bank. African Economic Outlook 2023. Abidjan: AfDB, 2023.

Amnesty International. Failure to Protect: Gender-Based Violence and Conflict in Africa. London: Amnesty International, 2023.

Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack. Education under Fire: 2015–2023. Geneva: GCPEA, 2023.

Institute for Security Studies (ISS). Youth, Employment, and Conflict in the Sahel Region. Pretoria: ISS, 2023.

Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2024. Berlin: TI, 2024.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Children Associated with Armed Forces and Armed Groups: Global Report 2024. New York: UNICEF, 2024.

United Nations Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources in the DRC. Final Report 2024. United Nations Security Council, 2024.

Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP). Conflict Data, 2000–2024. Uppsala University, Sweden, 2024.

World Bank. Fragility, Conflict, and Violence in Africa: Data Report 2024. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2024.

Biblical and Theological Works

The Holy Bible, New International Version (NIV), 2011.

Gerhard von Rad. Old Testament Theology. New York: Harper & Row, 1962.

Mugambi, J. N. K. African Christian Theology: An Introduction. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, 1995.

Journal Articles and Essays

Eze, Emmanuel Chukwudi. “The African Concept of Rebellion and Justice.” Journal of African Philosophy, vol. 14, no. 2, 2021, pp. 34–58.

Katongole, Emmanuel. “Theology of Peacebuilding in Africa.” International Journal of Peace Studies, vol. 26, no. 1, 2019, pp. 15–39.

Moyo, Dumisani. “Youth Unemployment and Conflict in Africa: An Interdisciplinary Perspective.” African Security Review, vol. 29, no. 3, 2020, pp. 207–225.