Uganda’s main opposition presidential contender, Robert Kyagulanyi—widely known by his stage name Bobi Wine—has said that if he wins the country’s upcoming election, he would carry out a comprehensive review of Uganda’s oil agreements with foreign energy companies and amend any terms he believes do not adequately benefit Ugandans.

Speaking in an interview in Kampala ahead of the presidential election scheduled for next week, Wine positioned natural resource governance as a key issue in his campaign against long-time leader President Yoweri Museveni. He said his administration would scrutinize existing oil contracts to ensure they align with national interests, particularly in terms of revenue sharing, transparency, and long-term development outcomes.

“We shall study all agreements,” Wine said during the interview. “And any part in those agreements that does not favour Ugandans will definitely be revised.”

Uganda is on the verge of becoming a commercial oil producer, with first output expected later this year. Production is set to begin from oil fields operated by France’s TotalEnergies, China’s CNOOC, and the state-owned Uganda National Oil Company. The foreign firms operate under production-sharing agreements, a common arrangement in the oil industry where companies recover costs and share profits with the host government.

Wine’s comments introduce an element of uncertainty into Uganda’s oil sector at a sensitive moment, as the country prepares to transition from exploration to full-scale production after years of delays. Uganda’s recoverable oil reserves are estimated at about 6.65 billion barrels, making it one of the largest onshore discoveries in sub-Saharan Africa in recent decades.

Oil was discovered in Uganda roughly 20 years ago, but development has progressed slowly. Disputes between the government and international oil companies over tax terms, infrastructure planning, and export routes have contributed to repeated postponements. In addition, environmental groups have raised concerns about the ecological and social impact of oil projects, including the planned crude export pipeline.

Neither Uganda’s information ministry nor the oil companies mentioned responded immediately to requests for comment on Wine’s remarks.

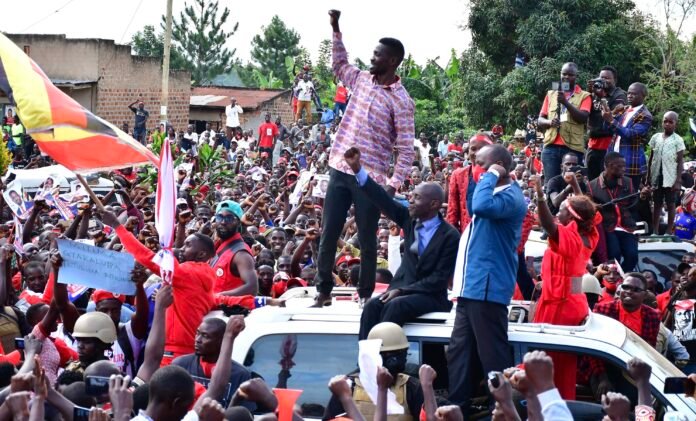

Wine, a former pop star turned politician, is contesting the presidency against Museveni for the second time. In the last election, he secured about 35% of the vote, according to official results, though he rejected the outcome and alleged widespread irregularities. Museveni, now 81, has ruled Uganda for four decades, making him one of Africa’s longest-serving leaders.

Beyond oil policy, Wine used the interview to sharply criticise Uganda’s Western partners, accusing them of prioritising strategic and economic interests over democratic values and human rights. He argued that foreign governments continue to provide financial and diplomatic support to Museveni’s administration despite repeated allegations of abuses against opposition figures and their supporters.

“These Western countries have laws that they can invoke to slap sanctions on those that violate human rights,” Wine said. “Unfortunately, they have not. So that comes off as if diplomacy is more important than democracy to them. It comes off as if business is more important than human rights.”

Human rights groups have long accused Ugandan security forces of using excessive force to suppress dissent, particularly during election periods. Wine claimed that he has personally been beaten by security personnel on two occasions while campaigning and said he has been prevented from holding rallies in certain parts of the country. According to Wine and the United Nations, hundreds of opposition supporters have been detained during the campaign.

The Ugandan government has consistently rejected allegations of politically motivated repression, maintaining that arrests and security actions are based on legitimate violations of the law and are necessary to maintain public order.

As Uganda approaches election day, the stakes are high not only politically but economically. Oil revenues are widely seen as a potential catalyst for development, but critics warn that without strong institutions and accountability, the sector could exacerbate inequality and corruption rather than reduce poverty.

Wine’s pledge to revisit oil agreements appears aimed at tapping into public concerns that Uganda’s natural wealth may not translate into tangible benefits for ordinary citizens. Whether such revisions would be feasible—or welcomed by investors—remains uncertain, but the comments underscore how central the oil sector has become to Uganda’s political debate.

With voters set to decide the country’s leadership in the coming days, the future direction of Uganda’s democracy, human rights record, and management of its oil resources are all firmly in the spotlight.

Source: Africa Publicity