Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Africa in the mid-2020s confronts a convergence of political instability, armed conflict, economic precarity, ecological stress, and democratic erosion that cannot be adequately explained through conventional policy failures alone. While external analyses often frame these challenges as governance deficits or resource constraints, such explanations obscure a deeper epistemic problem: the persistent misalignment between Africa’s lived realities and the knowledge systems that continue to shape its governance, development strategies, and crisis responses. The endurance of conflict in regions such as eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, the Sahel, and northern Mozambique, alongside shrinking civic space and fragile public institutions across the continent, suggests that dominant governance frameworks remain ill-suited to African social, historical, and cultural contexts. This misalignment has produced states that function procedurally but lack deep legitimacy, and policies that appear rational in design yet fail in practice.

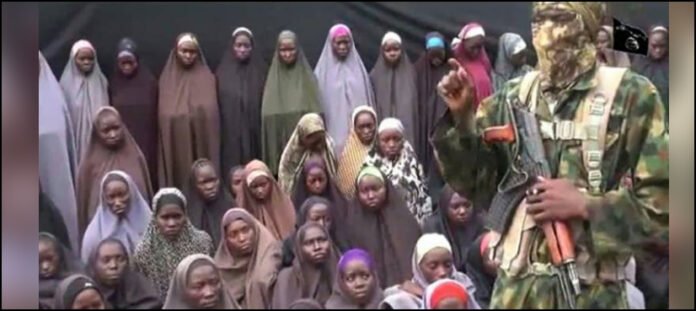

Contemporary armed conflicts in Africa illustrate the limits of externally mediated solutions that privilege military stabilization and technocratic peace processes over social repair. In eastern Congo, armed violence persists not only because of weak state presence but also due to the erosion of customary authority structures that once regulated land, labor, and intercommunal relations. Similarly, the war in Sudan has exposed how state collapse is exacerbated when political power is severed from communal moral authority, leaving violence to operate without restraint or accountability. International interventions, though often well intentioned, frequently prioritize ceasefires and elite negotiations while neglecting the deeper social fractures rooted in historical dispossession, resource extraction, and the marginalization of local governance systems. The result is a cycle of temporary containment rather than durable peace.

Democratic governance across Africa faces a parallel crisis of legitimacy. Although most African states formally adhere to constitutional rule, multiparty elections, and judicial independence, these institutions often fail to command public trust. Executive consolidation of power, the criminalization of dissent, and the instrumentalization of law for political control reflect not only authoritarian tendencies but also the transplantation of governance models that emphasize procedural compliance over relational accountability. Historically, many African societies governed through systems in which authority was distributed, leaders were morally constrained, and accountability was enforced through communal sanction rather than coercive law. The displacement of these systems has produced governance structures that are legally recognizable yet socially estranged, intensifying citizen disengagement and political instability.

Economic and development policies further reveal the costs of epistemic dependency. Development strategies continue to privilege extractive industries, foreign investment incentives, and growth metrics that obscure inequality, ecological degradation, and social dislocation. The rapid expansion of digital technologies and financial platforms, often celebrated as signs of progress, has unfolded within weak regulatory environments, exposing populations to exploitation and deepening structural exclusion. Public health systems, meanwhile, remain highly vulnerable to external funding shifts, demonstrating a reliance on donor priorities rather than resilient, community-rooted health infrastructures. These patterns reveal a development paradigm that remains externally oriented, insufficiently attentive to indigenous economic logics and communal welfare systems.

At the heart of these challenges lies the systematic marginalization of Indigenous Knowledge Systems, which have long provided African societies with frameworks for governance, conflict resolution, environmental stewardship, and social care. Colonial and postcolonial state formation relegated these systems to the realm of tradition, treating them as obstacles to modernization rather than as dynamic and adaptive forms of knowledge. Yet indigenous political philosophies, ecological practices, and moral economies continue to shape everyday life for millions across the continent. Their exclusion from formal governance has not only eroded social cohesion but has also deprived African states of locally legitimate tools for addressing contemporary crises.

A viable way forward for Africa therefore requires an epistemic reorientation that recenters Indigenous Knowledge Systems within modern governance frameworks. This does not entail rejecting scientific knowledge or constitutional governance, but rather integrating indigenous epistemologies into the design and operation of state institutions. In the realm of peace and security, customary conflict resolution mechanisms such as councils of elders, restorative justice rituals, and community reconciliation processes offer proven methods for addressing grievances, restoring trust, and reintegrating offenders. Incorporating these mechanisms into national peacebuilding strategies can enhance legitimacy and sustainability, particularly in contexts where formal judicial systems are inaccessible or mistrusted.

Governance reform must also draw from indigenous political traditions that emphasize moral leadership, shared authority, and collective responsibility. In many African societies, leaders were understood as stewards accountable to both the living community and ancestral moral orders, with power constrained by communal norms rather than centralized coercion. Translating these principles into contemporary governance through decentralization, community oversight structures, and participatory decision-making can counter executive overreach and rebuild trust between citizens and the state. Such reforms are especially critical in contexts where legal instruments have been used to suppress dissent rather than protect rights.

Indigenous ecological knowledge is indispensable for addressing climate change, food insecurity, and environmental conflict. Traditional land management systems, water conservation practices, and biodiversity preservation strategies have enabled African communities to adapt to environmental variability for generations. As climate stress increasingly fuels displacement and violence, integrating indigenous ecological knowledge into national development and security planning can enhance resilience while safeguarding ecosystems. This requires recognizing local communities as co-producers of environmental governance rather than passive beneficiaries of externally designed policies.

Public health systems likewise stand to benefit from the integration of indigenous knowledge. Traditional healing practices, maternal care networks, and communal support systems play a crucial role in health education, early intervention, and social well-being, particularly in rural and marginalized areas. A pluralistic health framework that respects indigenous knowledge alongside biomedical science can improve trust, access, and outcomes, especially where formal health infrastructure remains limited.

Ultimately, Africa’s contemporary crises reflect not only institutional weaknesses but epistemic exclusions. Sustainable peace, democratic governance, and equitable development will remain elusive unless African societies reclaim the authority to define problems and solutions on their own terms. Re-centering Indigenous Knowledge Systems within modern governance frameworks offers a path toward ethical legitimacy, social resilience, and long-term stability. Africa’s future depends not on the wholesale adoption of external models, but on the deliberate synthesis of indigenous wisdom and contemporary institutional practice.

Bibliography

Asante, M. K. (2007). An Afrocentric Manifesto. Polity Press.

Dei, G. J. S. (2012). Indigenous Knowledge and the Integration of Knowledge Systems. Springer.

Mbiti, J. S. (1990). African Religions and Philosophy. Heinemann.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton University Press.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2018). Epistemic Freedom in Africa. Routledge.

Odora Hoppers, C. A. (2002). Indigenous Knowledge and the Integration of Knowledge Systems. New Africa Books.

Wiredu, K. (1996). Cultural Universals and Particulars: An African Perspective. Indiana University Press.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author and do not in anyway reflect the opinions or editorial policy of Africa Publicity