By: Isaac Christopher Lubogo

Abstract

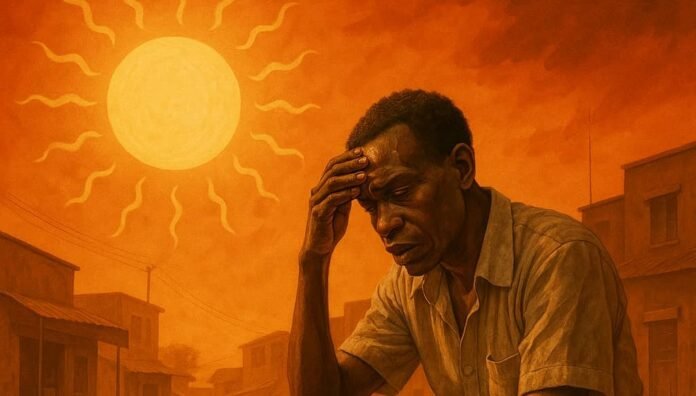

Uganda is experiencing increasingly frequent and intense episodes of extreme heat, with significant implications for public health, productivity, and social wellbeing. This article situates Uganda’s recent heat conditions within global climate change science, regional East African climate dynamics, and local environmental drivers. Using secondary climate and public-health data, the paper analyses the physiological, epidemiological, and socio-economic impacts of prolonged heat exposure in a low-income tropical context. It argues that extreme heat should be recognised not merely as an environmental issue but as an emerging public health emergency requiring institutional adaptation. The article concludes that without proactive mitigation and heat-adaptation strategies, Uganda risks escalating preventable morbidity and mortality associated with climate-induced thermal stress.

1. Introduction

Heat is increasingly recognised as one of the most deadly climate-related hazards globally, yet it remains under-addressed in many low-income countries. In Uganda, rising ambient temperatures and recurrent heatwaves have transitioned from episodic discomfort to structural environmental stress. Public discourse frequently describes the situation as “excessive heat,” but such characterisation risks minimising the severity of a phenomenon now well-documented in scientific literature.

This article argues that Uganda’s current heat conditions represent a convergence of global climate change, regional climate variability, and local environmental degradation, producing measurable public health risks. While extreme heat has long been studied in temperate economies, its implications in tropical, low-resource contexts require greater scholarly and policy attention. The central objective of this article is therefore to provide a scientifically grounded analysis of extreme heat in Uganda and to assess its public health consequences using existing climate and epidemiological data.

2. Methods and Analytical Framework

This study adopts a qualitative desk-review methodology, analysing secondary data from peer-reviewed scientific literature, international climate assessments, regional climate institutions, and global public health organisations. Sources include reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the World Health Organization (WHO), the IGAD Climate Prediction and Applications Centre (ICPAC), and peer-reviewed journals in climatology and epidemiology.

The analysis integrates climate science with public health frameworks, focusing on heat exposure pathways, vulnerability factors, and adaptive capacity. While no primary data are generated, triangulation across multiple authoritative sources ensures reliability and validity.

3. Climate Science Context: Why Uganda Is Getting Hotter

3.1 Global Warming and Rising Temperature Baselines

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report confirms that global surface temperatures have already increased by approximately 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels, primarily driven by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC, 2023). Importantly, warming trends disproportionately affect tropical regions by increasing the frequency and intensity of heat extremes rather than simply raising mean temperatures.

Uganda’s climatic records show a clear rising trend. Mean annual temperatures have increased by approximately 1.3°C since the early twentieth century, with projections indicating an additional rise of 1.5–3.0°C by mid-century under current emission scenarios (McSweeney et al., 2010; IPCC, 2023). These shifts significantly elevate baseline thermal exposure for populations that already live near physiological heat tolerance thresholds.

3.2 Regional Climate Variability in East Africa

Large-scale climatic drivers such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) further influence thermal extremes in East Africa. Research demonstrates that when ENSO variability coincides with long-term warming, compound heat events occur with greater severity and duration (Nicholson, 2017).

Seasonal climate outlooks by ICPAC have consistently reported above-average temperatures across Uganda in recent years, including documented heatwaves affecting both urban and rural districts (ICPAC, 2024). These climatic patterns indicate that extreme heat events are becoming more frequent rather than anomalous.

3.3 Local Environmental Amplifiers

Local land-use changes intensify heat exposure. Rapid urbanisation, deforestation, wetland encroachment, and reliance on heat-absorbing building materials contribute to urban heat island effects and reduced nocturnal cooling (Oke et al., 2017). In Ugandan cities, night-time temperatures often remain elevated, preventing physiological recovery from daytime heat stress and increasing cumulative health risks.

4. Public Health Implications of Extreme Heat

4.1 Physiological Pathways of Heat-Related Illness

Extreme heat overwhelms human thermoregulation, leading to dehydration, heat exhaustion, and potentially fatal heatstroke. Epidemiological studies demonstrate strong associations between high ambient temperatures and increased cardiovascular, renal, and neurological morbidity (WHO, 2023).

Heat exposure increases blood viscosity and cardiac workload while reducing renal perfusion, mechanisms linked to increased mortality during heatwaves (Kjellstrom et al., 2016). These effects are amplified in tropical settings where high humidity impairs evaporative cooling.

4.2 Differential Vulnerability and Social Inequality

Heat vulnerability is socially stratified. Children, older adults, pregnant women, individuals with chronic illness, and those engaged in outdoor labour face disproportionate risk (WHO, 2023). In Uganda, large portions of the population depend on agriculture and informal outdoor work, increasing exposure duration and severity.

Afrobarometer data indicates that over 70% of Ugandans report experiencing severe heat conditions affecting daily life, with higher vulnerability among low-income households lacking access to cooling, improved housing, or healthcare (Afrobarometer, 2022).

4.3 Interaction with Air Pollution and Disease Burden

Extreme heat exacerbates air pollution by trapping particulate matter and accelerating ozone formation. Studies across sub-Saharan Africa show that combined exposure to heat and air pollution significantly increases respiratory morbidity and mortality (Silva et al., 2017). These interactions compound Uganda’s existing burden of non-communicable and infectious diseases.

5. Socio-Economic and Cognitive Effects

Thermal stress also affects cognitive performance, productivity, and educational outcomes. Empirical research demonstrates that high temperatures reduce concentration, learning capacity, and labour output, particularly in settings without climate-controlled environments (Zander et al., 2015; Kjellstrom et al., 2016).

In Ugandan classrooms and workplaces—often overcrowded and poorly ventilated—heat stress undermines human capital development and economic resilience. These indirect effects magnify long-term development costs beyond immediate health outcomes.

6. Adaptation, Policy, and Institutional Implications

The WHO identifies extreme heat as a priority climate-related health risk requiring early warning systems, urban greening, public awareness, and health system preparedness (WHO, 2023). In Uganda, heat adaptation remains insufficiently integrated into health planning, urban development, and environmental governance.

Evidence-based interventions—such as tree cover expansion, protection of wetlands, climate-sensitive housing standards, and public heat advisories—have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing heat-related morbidity. Failure to implement such measures risks escalating preventable illness and mortality as warming intensifies.

7. Conclusion

The excessive heat currently experienced in Uganda is consistent with established climate science and presents a significant public health challenge. Rising temperatures result from the interaction of global climate change, regional climate variability, and local environmental degradation. Scientific evidence demonstrates that extreme heat threatens health, productivity, education, and social stability, particularly among vulnerable populations.

Recognising extreme heat as a public health emergency rather than a seasonal inconvenience is essential. Uganda’s long-term resilience will depend on integrating climate adaptation into health systems, urban planning, and environmental policy. Without such action, heat-related risks are likely to intensify as climate change accelerates.

References

Afrobarometer (2022) Africans’ experiences and perceptions of climate change. Policy Paper No. 79.

Glaser, J. et al. (2016) ‘Climate change and chronic kidney disease of unknown cause in agricultural communities’, Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 11(8), pp. 1479–1486.

IGAD Climate Prediction and Applications Centre (ICPAC) (2024) Seasonal climate outlook for the Greater Horn of Africa. Nairobi: ICPAC.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2023) AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Geneva: IPCC.

Kjellstrom, T., Holmer, I. and Lemke, B. (2016) ‘Workplace heat stress, health and productivity’, Global Health Action, 2(1), pp. 1–6.

McSweeney, C., New, M. and Lizcano, G. (2010) UNDP Climate Change Country Profile: Uganda. New York: UNDP.

Nicholson, S.E. (2017) ‘Climate variability and rainfall in eastern Africa’, Reviews of Geophysics, 55(3), pp. 590–635.

Oke, T.R. et al. (2017) Urban Climates. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Silva, R.A. et al. (2017) ‘The effect of future air pollution on premature mortality’, Nature Climate Change, 7(9), pp. 647–651.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2023) Heat and Health. Geneva: WHO.

Zander, K.K. et al. (2015) ‘Heat stress and labour productivity’, Nature Climate Change, 5, pp. 647–651.