By Mahmud Tim Kargbo

When President Dwight D. Eisenhower delivered his farewell address in 1961, he warned against the rise of a “military-industrial complex”, a structure in which state defence and private profit dangerously intertwine to undermine democracy. Sierra Leone, though small in geography and resources, now faces a similar moral crisis. Over two decades after its civil war, the nation’s defence procurement system has evolved into a labyrinth of secrecy, inefficiency and political patronage that threatens to erode the democratic gains painfully achieved after conflict.

In the aftermath of war, Sierra Leone pledged to rebuild not only its army but its democratic conscience. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Report cautioned that the abuse of state power, corruption within the armed forces, and the absence of accountability were among the root causes of national collapse (http://www.sierraleonetrc.org). Two decades later, the same problems persist, hidden in the language of procurement, logistics and national security.

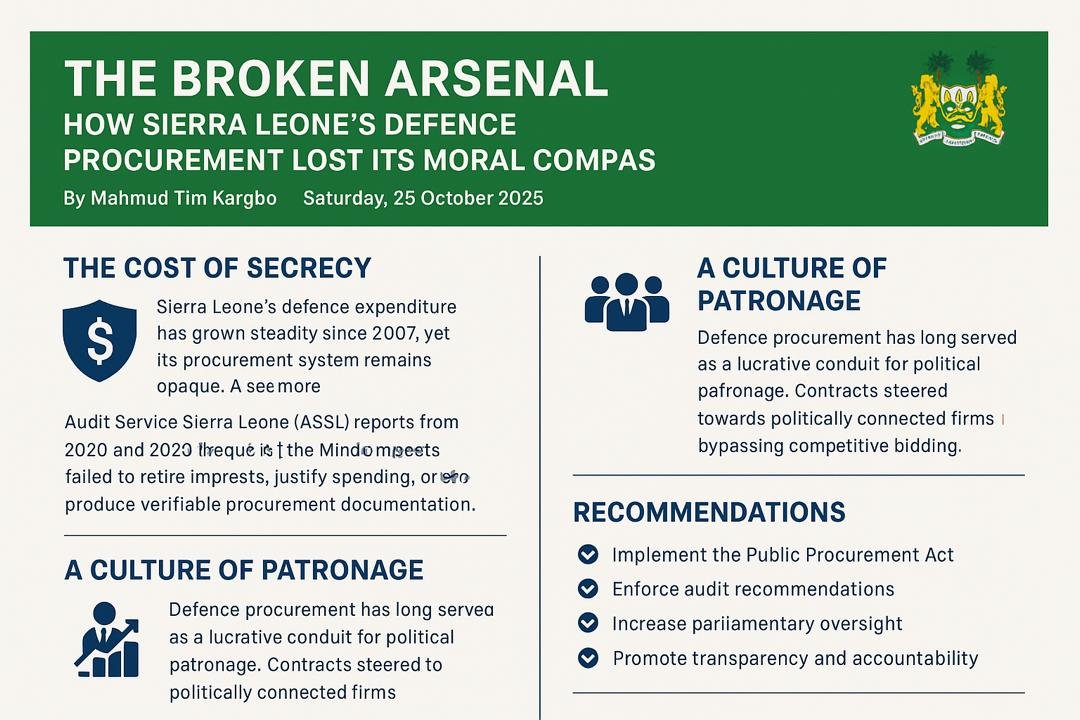

The Cost Of Secrecy

Sierra Leone’s defence expenditure has grown steadily since 2007, yet its procurement system remains mired in opacity. According to the Audit Service Sierra Leone (ASSL) reports between 2020 and 2023, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) consistently failed to retire imprests, justify spending, or produce verifiable procurement documentation (http://www.auditservice.gov.sl). The pattern is unmistakable: large budgets are allocated, accountability is neglected, and institutional inertia shields wrongdoing from consequence.

Under the All People’s Congress (APC) administration of Ernest Bai Koroma, audit findings from 2014 to 2016 exposed billions of unaccounted Leones in procurement transactions, all defended under the convenient label of “security confidentiality”. The Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) government of Julius Maada Bio, despite its “New Direction” slogan, has not broken this pattern. The 2021 and 2022 audit reports again revealed that contracts were awarded without competitive tendering and that funds were used for vaguely defined operational expenses.

The National Public Procurement Authority (NPPA), mandated under the Public Procurement Act 2016 to regulate all public contracting, has repeatedly cited the MoD’s non-compliance (http://www.nppa.gov.sl). Yet enforcement remains weak. While defence officials invoke national security to justify secrecy, that veil often protects inefficiency more than sovereignty.

A Legacy Of Delay and Waste

Sierra Leone’s procurement machinery is notoriously slow and overly centralised, causing chronic delays in delivery. Vehicles, communications equipment and essential supplies frequently arrive years after purchase, often obsolete upon arrival.

A striking example emerged in the 2019 to 2020 audit reports, which noted severe delays in delivering refurbished military trucks and communications gear for regional deployments. The equipment arrived long after the warranty had expired, while total costs exceeded initial estimates by over 25 percent. Despite this, no investigation or sanction followed.

The TRC had warned that rebuilding the armed forces required accountability over hierarchy. Yet successive governments have reduced its recommendations to symbolic gestures. The APC years entrenched political patronage within defence contracting; the SLPP years have substituted rhetoric for reform. Both administrations have perpetuated a culture where inefficiency is tolerated and mediocrity institutionalised.

The Burden Of Outdated Platforms

Sierra Leone’s defence legacy is not one of advanced technology, but of decaying infrastructure. The MoD continues to maintain obsolete vehicle fleets and analogue communications systems rather than investing in digital capability and modern logistics. The 2003 Defence White Paper envisioned a transition from external dependence to local competence, a vision now largely abandoned.

Reliance on foreign donors, particularly the United Kingdom and China, continues to define Sierra Leone’s military development. This dependence exposes a deeper weakness: strategic autonomy remains aspirational. As in the critique by American scholar Ralph L. DeFalco III, Sierra Leone’s dilemma is not industrial but institutional, a bureaucracy paralysed by procedural comfort and political interference that resists innovation and accountability.

A Culture of Patronage

Defence procurement has long served as a lucrative conduit for political patronage. During the APC government, several contracts were reportedly steered towards politically connected firms, bypassing competitive bidding. The SLPP administration, while promising transparency, has often perpetuated similar practices.

The NPPA’s 2022 assessment revealed that most MoD contracts were awarded through “restricted bidding” or “direct procurement”, mechanisms meant for emergencies but now used as standard practice (http://www.nppa.gov.sl). The Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC), though empowered by the Anti-Corruption Act 2008 (amended 2019), has acted selectively in defence-related investigations (http://www.anticorruption.gov.sl). Under Koroma, sensitive cases faded quietly; under Bio, they often ended in administrative reprimands rather than criminal prosecutions.

The TRC’s warning that “impunity in public administration erodes trust and endangers peace” rings truer than ever. Sierra Leone’s procurement culture has become a mirror of its political system, one where power shields itself from consequence while symbolic reforms pacify public outrage.

Democratic Oversight In Decline

The 1991 Constitution empowers Parliament to scrutinise all public expenditure, including defence, under Sections 105 and 119 (http://www.sierraleone.org/Laws/constitution1991.pdf). Yet parliamentary oversight has been more ceremonial than substantive. Under the APC, hearings were often mere endorsements. Under the SLPP, sessions on defence allocations are held behind closed doors, their findings rarely published.

This reluctance has historical roots. Having endured military rule from 1992 to 1996, Sierra Leone’s civilian leaders have grown wary of challenging the armed forces. The result is a constitutional paradox: the sector most in need of transparency remains the least accountable.

The Struggle For Institutional Independence

Despite political resistance, the Audit Service Sierra Leone (ASSL) continues to perform commendably. Its reports have become the nation’s only consistent mechanism for exposing procurement malpractice. Yet its recommendations are too often ignored by Parliament and the Ministry of Finance, eroding deterrence. Exposure without enforcement turns accountability into ritual.

The NPPA and ACC, though conceived as the twin pillars of financial integrity, remain underfunded and politically constrained. Their enforcement targets minor officials while senior architects of systemic inefficiency remain immune. Sierra Leone’s institutions of oversight are thus armed with principles but deprived of power, an arsenal of accountability rendered toothless.

The Moral and Strategic Cost

The consequences of this dysfunction are profound. When procurement funds are squandered or misused, soldiers are left ill-equipped, operations falter, and morale collapses. Sierra Leonean troops have served with courage on international peacekeeping missions in Somalia and Sudan, yet at home they face shortages of basic supplies and delayed allowances.

This paradox reveals a deeper irony: a nation that contributes to global peacekeeping cannot guarantee accountability in its own defence administration. Both the APC and SLPP governments have spoken the language of patriotism but failed to embody it in practice. One pursued visibility, the other virtue-signalling. Neither built a transparent, efficient defence system worthy of its soldiers.

Towards a New Arsenal of Accountability

To rebuild trust and competence within its defence sector, Sierra Leone must undertake reform in four decisive areas:

Full Implementation of the Public Procurement Act: The MoD should publish procurement data, including tender outcomes, contract values and supplier information, while maintaining legitimate security discretion.

Enforcement of Audit Recommendations: Parliament and the Ministry of Finance must ensure that every audit infraction triggers either disciplinary or criminal action.

Transparent Parliamentary Oversight: The Defence Committee must hold open sessions and release reports accessible to civil society and the press.

Civic Vigilance and Whistleblower Protection: Citizens, journalists and watchdog organisations should be empowered to track defence spending without fear of reprisal.

These reforms echo the TRC’s broader vision: a governance culture rooted in truth, accountability and civic duty.

The Moral Frontline

Sierra Leone’s armed forces have earned international respect through their discipline abroad. Yet the nation’s true moral frontier lies not on foreign battlefields but in the integrity of governance at home. The TRC once declared, “Without accountability, there can be no reconciliation.” Today, that axiom applies as urgently to public procurement as it once did to peacebuilding.

Eisenhower’s warning endures: unchecked power corrodes democracy. In Sierra Leone, unchecked secrecy corrodes trust. The country’s “arsenal of democracy” must evolve into an “arsenal of accountability”. Until Sierra Leone learns to defend truth with the same dedication it defends territory, its arsenal will remain broken, powerful in rhetoric but hollow in purpose.