By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Introduction

Uganda’s encounter with HIV/AIDS is not simply a story of disease and medicine—it is a mirror reflecting the nation’s soul, its resilience, and its struggle to reconcile ancient wisdom with modern science. Since the early 1980s, when the first cases of what was then known as “Slim Disease” surfaced along the shores of Lake Victoria, Uganda has stood at the crossroads of public health innovation and cultural self-examination. The epidemic did not arrive in a vacuum; it found a society already undergoing deep transitions—from precolonial communal ethics to colonial moral intrusion, from post-independence turbulence to donor-driven policy experiments. To understand what truly works and what fails in Uganda’s HIV prevention journey, one must read not only the biomedical data but also the deeper moral, historical, and socio-economic texts that have shaped the nation’s response. Uganda’s path reveals how health interventions succeed when rooted in cultural consciousness and fail when detached from the lived realities of the people.

Precolonial Foundations: Indigenous Ethics and Communal Health

Long before the arrival of colonial administrators or biomedical doctors, the peoples of Uganda possessed intricate health systems governed by moral codes, spiritual disciplines, and collective responsibilities. Among the Baganda, Banyankore, Acholi, and Basoga, sexual relationships were deeply embedded in clan laws, taboos, and initiation rituals that maintained social balance and protected communal well-being. The Buganda Kingdom’s clan exogamy rule, for instance, not only prevented incest but also reinforced the sacredness of the body as part of the cosmic order (Kagwa, 1934). The Banyankore’s okuteera ebisika—premarital mentorship between older and younger women—instilled respect, hygiene, and restraint, while male initiation among the Bagisu cultivated discipline and moral self-control (Karwemera, 1990). Sexual immorality was often linked to spiritual contamination, not just physical risk. Healing was holistic—combining herbal medicine, confession, and ritual reconciliation.

In this moral ecology, prevention was not a campaign but a way of life. However, colonial contact disrupted this equilibrium. Missionaries, while introducing literacy and modern medicine, condemned indigenous sexual customs as “pagan,” dismantling traditional educational systems without understanding their preventive functions (Tamale, 2011). The spiritual dimension of health—rooted in ancestral respect and communal accountability—was replaced with guilt-based moralism imported from Victorian Europe. Where precolonial societies had used dialogue, ritual, and mentorship to regulate sexuality, colonial religion imposed silence and shame. This moral rupture would later create a vacuum that amplified vulnerability when HIV arrived—a disease that thrived precisely where sexuality could no longer be discussed openly or managed communally.

Colonial and Early Postcolonial Transitions: Modernity and the Silence of Shame

By the 1950s, Uganda was undergoing a metamorphosis under colonial rule. Modern education, urban migration, and Christianity reshaped identities and sexual behaviors. The British colonial health system prioritized tropical diseases—malaria, sleeping sickness, and smallpox—while sexually transmitted infections were relegated to moral discourse rather than public health (Iliffe, 2006). Sex became both sensationalized and censored. The introduction of urban centers such as Kampala, Jinja, and Entebbe created environments of anonymity where traditional norms of sexual accountability weakened. Migration patterns brought men far from their families, fostering extramarital relations and transactional sex as survival mechanisms. The rise of prostitution around military barracks and trading centers foreshadowed the networks through which HIV would later spread.

The early postcolonial years, though filled with optimism, failed to restore moral or institutional stability. Political turbulence under Milton Obote and Idi Amin devastated Uganda’s health infrastructure. By the 1970s, hospitals lacked basic drugs, medical research collapsed, and thousands of health workers fled into exile. Cultural norms that once guided behavior were eroded by decades of war and economic hardship. When HIV/AIDS began to appear in Rakai District in the late 1970s, it found a society simultaneously over-Christianized in rhetoric yet under-anchored in genuine moral structure. The illness, called Slim because of the severe wasting it caused, was initially treated as witchcraft or divine punishment. Public denial, stigma, and moral panic silenced communities that might have mobilized early prevention. Thus, the colonial bequest of sexual silence and the postcolonial inheritance of health decay together laid the foundation for Uganda’s initial unpreparedness.

The Museveni Era and the ABC Model: Early Successes and Cultural Resonance

When President Yoweri Museveni assumed power in 1986, Uganda was ravaged by war and despair, but also uniquely positioned for a health rebirth. Museveni’s government, advised by local doctors and international agencies, launched the now-famous ABC strategy—Abstain, Be faithful, and use Condoms—a culturally hybrid model that blended moral, behavioral, and biomedical logic. Unlike many African leaders who denied AIDS or blamed foreigners, Museveni openly acknowledged the epidemic, encouraging communities to discuss it publicly. The campaign utilized radio, churches, mosques, schools, and traditional leadership structures, transforming prevention into a national conversation. Between 1992 and 2001, HIV prevalence dropped from approximately 15% to 5%, a global record (UNAIDS, 2003).

What worked during this era was not only the simplicity of the message but the authenticity of ownership. The ABC model resonated with Uganda’s moral landscape: “Abstain” echoed Christian virtues and ancestral restraint; “Be faithful” reflected traditional marriage ethics; and “Condom use” represented modern pragmatism. Community leaders were empowered to localize messaging in their languages, using folktales, proverbs, and drama to demystify the disease. Grassroots women’s groups like TASO (The AIDS Support Organization) emerged as sanctuaries of compassion, where the sick were cared for without judgment. The success of Uganda’s prevention in the 1990s demonstrated that when public health aligns with local culture and leadership transparency, even an epidemic can be humanized and managed.

The Turn of the Millennium: Donor Fatigue, Global Agendas, and Policy Fragmentation

The dawn of the 21st century, however, marked a turning point from moral clarity to policy confusion. The entry of large international donors such as PEPFAR (U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) and the Global Fund brought immense resources but also fragmented priorities. Uganda’s prevention programs became donor-driven rather than community-centered. Abstinence-only campaigns, funded under American conservative agendas, undermined the earlier balance between morality and science (Parkhurst, 2013). Simultaneously, the shift toward antiretroviral therapy (ART) as the centerpiece of intervention reduced emphasis on prevention. The country that had been praised for grassroots innovation became a recipient of externally dictated programs.

Culturally, Uganda was also changing. By 2024, 78% of Ugandans were under 30 years old (UBOS, 2024). A generation raised in the digital era faced new temptations and new freedoms: social media romanticized risky behaviors, pornography proliferated, and economic instability drove many youth into transactional relationships. Churches, once central to moral guidance, became politically entangled or commercially diluted. Prevention messaging lost coherence, alternating between puritanical abstinence sermons and flashy condom promotions. The HIV prevalence, which had fallen dramatically, plateaued and began to rise slightly among adolescents and young women—reflecting a gap between knowledge and power, especially in gender relations.

What Works Today: Combination Prevention and Cultural Reconnection

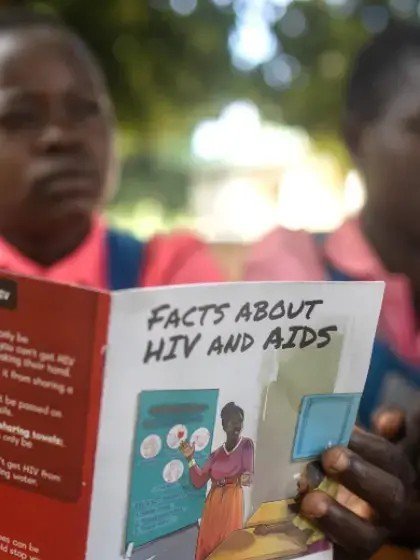

Contemporary evidence shows that no single intervention can control HIV; what works is the combination approach that integrates biomedical, behavioral, and structural strategies. Male circumcision, proven to reduce transmission risk by up to 60%, has been widely adopted, with over 70% of eligible men circumcised by 2023 (Ministry of Health, 2023). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) offers protection for high-risk groups, while self-testing kits have democratized access to diagnosis. Yet these biomedical tools succeed only when wrapped in cultural understanding. In rural districts like Mbale and Mbarara, community dialogues using folk theater and radio storytelling have reignited traditional communication forms that bridge science and culture.

Moreover, digital innovations such as the Obulamu? campaign employ social media influencers, local dialects, and humor to reach urban youth. Religious organizations like the Inter-Religious Council of Uganda have revived faith-based engagement in nonjudgmental ways, emphasizing compassion over condemnation. NGOs working with boda-boda riders, market women, and students have shown that peer-led education sustains behavior change better than top-down preaching. These layered interventions, rooted in trust and respect for local wisdom, embody the principle that effective prevention must be as social as it is scientific.

What Fails: Stigma, Inequality, and the Fragmentation of Moral Discourse

Despite progress, multiple failures persist. Abstinence-only education has failed to protect youth, especially girls, who face early marriage, coercion, or sexual exploitation. Over 60% of new infections occur among young women and adolescent girls (UNAIDS, 2024), revealing deep gender inequalities. Poverty and transactional sex continue to fuel vulnerability, yet economic empowerment remains underfunded in prevention budgets. Programs that ignore these structural realities merely preach without transforming conditions.

Stigma remains one of the most corrosive barriers. Although public discourse about HIV is freer today, subtle discrimination lingers in workplaces, schools, and faith institutions. Some pastors and imams still promote prayer-healing narratives that discourage adherence to treatment, reflecting a moral confusion between faith and fatalism. Corruption also undermines sustainability; misappropriated donor funds have crippled trust and continuity. Urban-rural disparities persist, with northern and island districts receiving limited outreach. Where prevention is divorced from cultural identity, it withers. A proverb from Acholi warns, “A tree without roots falls with the first wind.” Many contemporary programs, though scientifically sound, fail precisely because they are rootless—designed in boardrooms, not in the hearts of communities.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

Uganda’s long war against HIV/AIDS is both a national narrative and a moral parable. What once worked—the cultural dialogue of the 1990s—must be reborn in a new generation’s language. Prevention today must combine science with justice: gender equality, youth empowerment, poverty reduction, and cultural restoration. The future of prevention lies not in imported ideologies but in the reclamation of moral agency. Communities must see prevention not as a foreign campaign but as a sacred duty to life. The spirit of Obuntu bulamu—shared humanity—remains Uganda’s most potent medicine. As a Luganda proverb reminds us, “Obulamu bwe bugagga”—“Life is the true wealth.” In preserving life through truth, compassion, and cultural integrity, Uganda can once again lead Africa in healing not only the body, but also the soul.

References

Avert. (2023). HIV and AIDS in Uganda. Retrieved from https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/uganda

Barnett, T., & Whiteside, A. (2002). AIDS in the Twenty-First Century: Disease and Globalization. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bikaako-Kajura, W., & Okello, D. (2006). Coping strategies of people living with HIV/AIDS in Uganda: A study of gender differences. African Journal of AIDS Research, 5(2), 123–130.

Foster, P. (2007). The ABC Approach to HIV Prevention: The Case of Uganda. World Bank.

Green, E. C. (2003). Rethinking AIDS Prevention: Learning from Successes in Developing Countries. Praeger Publishers.

Iliffe, J. (2006). The African AIDS Epidemic: A History. James Currey.

Kagwa, A. (1934). The Customs of the Baganda. Oxford University Press.

Karwemera, A. M. (1990). The Abasigi and Their Cultural Heritage. Fountain Publishers.

Kinsman, J. (2010). AIDS Policy in Uganda: Evidence, Ideology, and the Making of an African Success Story. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kirby, D., & Halperin, D. (2008). Success in Uganda: Why was it achieved and will it continue? Sexual Health, 5(1), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH07033

Ministry of Health, Uganda. (2003). National HIV/AIDS Policy: Prevention and Control. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

Ministry of Health, Uganda. (2023). HIV and AIDS Progress Report 2023. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

Ntozi, J. P. M. (2002). HIV/AIDS in Uganda: How has the household coped with the epidemic? In J. P. M. Ntozi & N. Nakanaabi (Eds.), The Continuing African HIV/AIDS Epidemic: Responses and Coping Strategies (pp. 155–176). Fountain Publishers.

Okware, S. I., Opio, A., Musinguzi, J., & Waibale, P. (2001). Fighting HIV/AIDS: Is success possible? Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 79(12), 1113–1120.

Parkhurst, J. (2013). The Politics of Evidence: From Evidence-Based Policy to the Good Governance of Evidence. Routledge.

Schneider, H., & Fassin, D. (2002). Denial and defiance: A socio-political analysis of AIDS in South Africa. AIDS, 16(S4), S45–S51.

Tamale, S. (2011). African Sexualities: A Reader. Pambazuka Press.

The AIDS Support Organization (TASO). (2022). Annual Report 2021–2022. Kampala: TASO Uganda.

Uganda AIDS Commission. (2022). National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 2021/22–2025/26. Kampala: Government of Uganda.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). (2024). National Population and Housing Census Report. Kampala: UBOS.

UNAIDS. (2003). Uganda HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Update. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

UNAIDS. (2019). Communities at the Centre: Global AIDS Update 2019. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

UNAIDS. (2022). Global AIDS Update: In Danger. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

UNAIDS. (2024). The Path That Ends AIDS: Uganda Country Data. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

UNICEF Uganda. (2023). Adolescent HIV Prevention and Care: Country Profile. Kampala: UNICEF Uganda.

Wawer, M. J., Serwadda, D.,