By: Isaac Christopher Lubogo

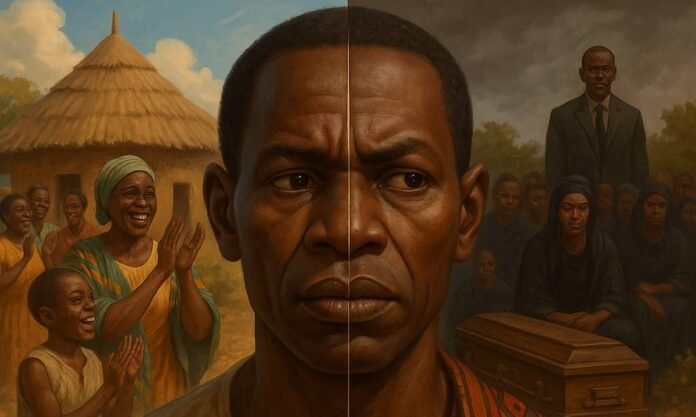

When we say Africans are defined by being extremely social, we are describing something deeper than mere friendliness or hospitality. We are touching the very heart of Ubuntu—that philosophy which says, “I am because we are.” Ubuntu is not just a cultural trait; it is the lens through which Africans interpret existence, community, and destiny. It is our greatest strength, but paradoxically, it is also our greatest weakness.

The Strength of Social Living

Ubuntu has given Africans a unique resilience. In times of famine, war, or poverty, survival has often depended not on individual strength but on communal support.

The Village Child: In many African communities, a child belongs to everyone. If one family has no food, the neighbor will provide. If one family cannot pay school fees, relatives and friends will come together for a fundraising (kafunda, harambee, okwegatta). This sense of shared responsibility ensures no one is completely abandoned.

The Funeral Gathering: When death strikes, Africans gather in hundreds, sometimes thousands, to mourn, console, and share food. Grief is never carried alone. Unlike individualistic cultures where mourning is often private, African mourning is loud, collective, and deeply healing.

The Market Scene: Markets across Africa are not just places of trade; they are social theatres. A simple trip to buy tomatoes may take an hour because you must greet, laugh, and check on one another’s wellbeing. Commerce is wrapped in conversation, and economics cannot be separated from relationships.

In these ways, Ubuntu weaves a safety net that has preserved communities through centuries of storms. It has made Africans some of the most resilient people on earth.

The Weakness of Social Living

Yet the same Ubuntu, when unchecked, becomes a burden. Our extreme socialness can suffocate individuality, discourage innovation, and perpetuate cycles of dependency.

The Burden of Obligation: A young graduate who finds a job is not simply working for themselves. The extended family expects constant support—school fees for cousins, medical bills for uncles, and upkeep for parents. This often discourages savings or investment, keeping many trapped in survival rather than prosperity.

The Culture of Silence: Because we are social, we fear breaking harmony. Wrongdoing by elders, leaders, or relatives is often left unchallenged for the sake of “peace.” Corruption festers in governments because whistleblowers are branded “traitors” to the communal bond. Ubuntu becomes a tool of conformity, not justice.

The Celebration Trap: We love to gather, celebrate, and socialize—sometimes to our own detriment. A funeral can consume resources that could build a house. A wedding can drive a family into debt. The social pressure to “be seen” often overrides sober financial priorities.

Thus, Ubuntu, when unbalanced, enslaves instead of liberating.

Everyday Narratives that Show the Paradox

1. The Student’s Burden

A bright young woman earns a scholarship to study abroad. But before leaving, she is summoned by relatives: “Don’t forget us when you succeed.” Her education, instead of being a personal achievement, becomes a communal debt she may never repay.

2. The Corrupt Leader

An African politician caught in corruption justifies himself: “I was helping my people.” Stealing becomes excusable if shared. Ubuntu is distorted to sanctify vice.

3. The Wedding Feast

A man borrows heavily to organize a wedding that feeds 800 people. The marriage begins with poverty, but the community praises him: “He respected us.” Ubuntu fuels honor, but at the cost of his family’s future.

A Philosophical Balance

African philosophers like Mogobe Ramose argue that Ubuntu is not merely about blind sociality but about restorative balance. To truly embrace Ubuntu, we must distinguish between solidarity that uplifts and solidarity that enslaves.

As the proverb goes: “The rope that ties the cow can also strangle it if pulled too hard.”

Ubuntu must therefore evolve. It must remain the source of compassion and resilience, but it must also leave room for individual growth, accountability, and justice.

Conclusion

Yes, Africans are extremely social—defined by Ubuntu. This is our sacred uniqueness. It is why the world finds our communities warm, our hospitality unmatched, and our resilience astonishing. But it is also why we sometimes remain trapped in poverty, silence, and over-dependence.

The challenge for this generation is to redefine Ubuntu for modern Africa—to preserve its warmth while pruning its weaknesses, to ensure that “I am because we are” does not erase the equally vital truth: “We are because I am.”