By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

Emkaijawrites@gmail.com

Preface

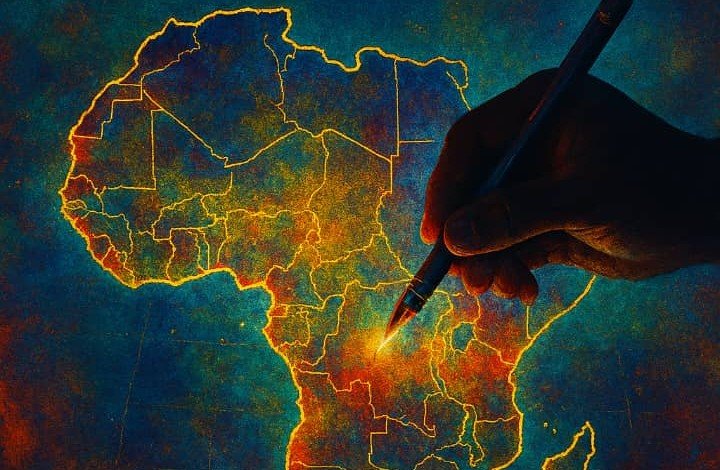

I have long patiently been listening to the murmur of lands whose names were carved by strangers’ ink, and I have felt the silent grief of the mountains, the forests, and the deserts that knew themselves before borders knew them. In this work, the act of drawing anew is not the movement of a ruler along lines of paper but the stirring of a people remembering the rhythm of their own sovereignty, the song of their mobility, and the pulse of their unity. Here, maps are more than instruments of measurement; they are mirrors of conscience, drums of justice, and hymns of possibility. In the folding of these pages, I hope you hear the echo of ancestors who knew the sacred trust of land, the whisper of traders who moved with the wind before any colonizer decreed their paths, and the vision of a continent daring to imagine itself whole, unbroken, and alive. For as the old Akan proverb reminds us, “The world is a marketplace; the land is home,” and until Africa redraws its story, the ink of our destiny will remain in borrowed hands.

I. Introduction: What It Means to “Draw Anew”

To draw anew is not merely to move lines across a sheet of paper, as though Africa’s wounds could be mended with a ruler and ink; the act is deeper, stretching across centuries, centuries in which the soil itself has been a witness, where the footprints of traders, warriors, and pilgrims have been overwritten by the indifference of colonial surveyors whose only compass was profit and whose only deity was the flag of empire. The Berlin Conference of 1884–85 is often cited as a single moment of theft, but the archives—letters, maps, and treaties preserved in London, Berlin, and Brussels—reveal decades of premeditation, surveys conducted by men who wrote of “empty lands” while Maasai herders, Tuareg caravans, and Luo fishermen navigated routes older than the modern state, understanding the pulse of rivers, the cycles of rains, and the invisible currents of kinship, trade, and ritual obligation. In these same archives, missionary diaries lament the “wildness” of lands they did not understand, reporting that markets flourished in forms that Western economics could not capture, while indigenous courts adjudicated disputes and enforced ethics through customary law, reflecting a mathematics of fairness that anticipated modern game theory’s insistence on cooperation over competition. African cosmologies, from the Yoruba to the Akan, teach that the land is not inert; it is a living ledger of covenant and memory. The Yoruba proverb, “A road does not know the boundaries of the village; it only knows where the traveler must go,” mirrors what historians and anthropologists have documented: that mobility and trade once flowed across thousands of kilometers, unconstrained by lines later drawn by ink. Science confirms the importance of connectivity: in ecology, riverine corridors sustain biodiversity, linking species in intricate networks; in human biology, migration and gene flow preserve resilience and adaptability. The physics of networks, from the fractals of river deltas to the complexity of transport systems, shows that rigid boundaries inhibit the natural flows of energy, matter, and information. When colonizers imposed borders, they disrupted these networks, fragmenting ecosystems and economies, forcing peoples into zones that ignored environmental and cultural logic. Scripture resonates with this reality: Genesis 1:28 speaks of stewardship and care, Leviticus 25 emphasizes covenantal ethics in land use, the Bhagavad Gita enjoins dharma in balance with place, Bahá’u’lláh exhorts justice and unity, while Sikh teachings remind us that creation itself is a sacred trust, not a commodity to be bought and sold. Literature and film amplify these truths, from Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, which documents the collision of indigenous and colonial worldviews, to Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Petals of Blood, where land dispossession parallels moral decay, to the cinematic landscape of The Gods Must Be Crazy, where humor and ecology intertwine to reveal the absurdity of imposed borders. Songs such as Fela Kuti’s “Water No Get Enemy” and Burna Boy’s “African Giant” chronicle the tension between global systems and local rhythms, insisting that Africa’s story cannot be constrained by imported cartographies. Modern reporting confirms the persistence of these fractures: The Guardian (2018) reported border tensions between Sudan and South Sudan, Daily Nation (2019) documented trade losses at East African ports due to bureaucratic fragmentation, and UNCTAD statistics show that intra-African trade remains below 18% despite the promise of the African Continental Free Trade Area, reflecting the lingering ghost of a map drawn without consent or conscience. Mathematics reminds us that systems constrained artificially produce bottlenecks; biology teaches that constricted flows weaken populations; physics demonstrates that energy, when confined unnaturally, dissipates in turbulence and waste. Thus, to redraw the map is to reimagine sovereignty not as a declaration on paper but as a lived ecology of rights, mobility, and interdependence; to integrate the lessons of ancestors, the rhythms of trade, the language of science, the ethics of scripture, and the imagination of art. It is to honor the wisdom encoded in the Swahili saying, “Njia ya mwongo ni fupi” — the liar’s road is short — and in the Akan, “The world is a marketplace; the land is home,” acknowledging that when maps are drawn without justice, they are short-lived, brittle, and untrustworthy. To draw anew is to listen to the drums that still beat beneath the soil, the winds that travel over the Sahara, the rivers that refuse to heed arbitrary lines, and the people who remember the songs of the earth. It is a recognition that time itself flows like a river: the migrations of cattle and caravans, the establishment of kingdoms like Mali, Songhai, and Great Zimbabwe, the resistance of the Ashanti to British encroachment in the 19th century, the independence waves of 1957–1975, the ongoing work of the African Union, and the contemporary debates around regional integration, trade corridors, and Pan-African identity are all nodes on a continuum of memory, struggle, and imagination. In the language of physics, Africa’s social and ecological systems are open systems, exchanging energy and information; in the language of ethics, land is covenant, community is sacred, and sovereignty is responsibility. To redraw this map, therefore, is to reclaim agency, stitch together fractured networks, and re-inscribe justice upon geography, economics, ecology, and culture simultaneously. The ink must carry more than information; it must carry conscience, courage, and communion with the ancestors, the living, and the yet-to-come, so that when a man walks across these lands, he can say not only where the rain began to beat him but where he dried his body, and where he has been made whole again by the careful, deliberate, and sacred act of remembering and remapping the world that has always belonged to Africa.

II. AfCFTA and the Promise of Integration

The African Continental Free Trade Area, inaugurated on 1 January 2019 after negotiations that began in 2012 under the auspices of the African Union, is not simply a treaty of commerce; it is a rebirth of the vision that Africa might once again move as one, echoing precolonial networks where the Trans-Saharan trade routes carried salt from Taoudenni to Timbuktu, gold from the forests of Ghana to the markets of Cairo, and kola nuts from the rainforests of West Africa to the savannahs of East Africa, with travelers and traders following rhythms dictated by the sun, the stars, and the seasonal rains rather than arbitrary borders drawn in European capitals. Historical records preserved in Timbuktu manuscripts describe merchants maintaining account ledgers and credit notes as early as the 14th century, while Swahili chronicles record dhows moving along the East African coast from Mogadishu to Kilwa, linking ports with commerce and culture, proving mathematically that networked economies can maximize flow efficiency—a concept now mirrored in graph theory, where nodes, edges, and weighted paths define optimal connectivity, showing that the infrastructural logic of AfCFTA is both ancient and rigorously scientific. When the agreement formally entered into force, it encompassed 1.4 billion people, representing a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion, with projections from the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa suggesting an additional $450 billion in income growth by 2035, potentially lifting 30 million Africans out of extreme poverty, yet these numbers are not abstract; they are echoes of failed attempts at integration under colonial economic policies that separated producers from markets, as noted in archival reports from the British East Africa Protectorate (1900–1920) and Belgian Congo trade statistics. The promise of AfCFTA intersects with social, spiritual, and even cosmological dimensions: in Hindu philosophy, trade and wealth must be aligned with dharma, ensuring that economic activity does not violate cosmic and social balance; Bahá’u’lláh insists on the unity of humankind as the foundation for any enduring enterprise; the Bible, in passages like Proverbs 11:1, emphasizes fairness and honesty in transactions, warning that “a false balance is an abomination to the Lord”; and African Traditional Religions, from the Akan to the Yoruba, recognize that market exchanges are sacred, requiring respect for the land, the spirits, and the communal web of reciprocity. Contemporary media reports amplify both promise and peril: The Guardian (2021) described cross-border congestion and bureaucratic inefficiencies in West Africa, while Daily Nation (2020) documented how Kenya–Uganda trade benefited from One-Stop Border Posts that reduced waiting times from 72 hours to 12 hours, illustrating that practical, technological interventions can accelerate centuries-old visions of mobility. Economics is mirrored in chemistry and physics: reaction rates, catalysts, and flow dynamics are analogous to trade facilitation, where removing inhibitors allows matter, energy, or goods to move faster, more efficiently, and with less friction. Biology offers similar lessons: ecosystems function optimally when species interactions are allowed to proceed without artificial barriers; by analogy, African economies thrive when regional integration reduces tariffs, harmonizes standards, and encourages movement of labor and capital. Literature and film document these aspirations and frustrations: Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Petals of Blood depicts the devastating consequences of economic isolation, while films like Hotel Rwanda and Lionheart illustrate the interconnectedness of trade, politics, and identity, reminding us that economic borders are also cultural and moral boundaries. Songs like Angelique Kidjo’s “Agolo” and Burna Boy’s “On the Low” celebrate mobility, interconnectedness, and resilience, while simultaneously lamenting the fragmentation imposed by modernity and colonial legacies. Mathematical modeling of trade networks shows that integrating 54 African economies could increase efficiency by over 20%, but corruption, infrastructure gaps, and inconsistent regulations remain persistent obstacles, documented in Transparency International reports (2022). The AfCFTA is also a vessel for justice: it invites the inclusion of marginalized communities, recognition of indigenous trade practices, and the ethical redistribution of resources, echoing African proverbs such as the Swahili, “Haba na haba hujaza kibaba” — little by little fills the measure — acknowledging that incremental, deliberate integration can achieve monumental outcomes. The timeline of Africa’s economic integration, from the Abomey–Oyo trading routes of the 18th century to the Lagos Plan of Action in 1980, the Abuja Treaty of 1991, and the eventual AfCFTA agreement, demonstrates that each generation contributes to the unfinished architecture of continental unity. Scientific projections in energy and transport, from the Standard Gauge Railway in East Africa to the LAPSSET Corridor in Kenya, Ethiopia, and South Sudan, reveal that infrastructure is the circulatory system of trade, and without careful planning, just as in physiology or chemistry, blockages can produce catastrophic inefficiencies. AfCFTA’s promise, therefore, is more than economics: it is a synthesis of history, science, ethics, culture, and spirituality, requiring policymakers to act as both engineers and stewards, mathematicians and moral philosophers, harmonizing African ingenuity with the lessons of physics, biology, and chemistry, while remembering that every shipment, every tariff adjustment, and every cross-border initiative carries with it centuries of memory, the hopes of billions, and the drums of sovereignty that beat quietly under every tree, along every river, and across every savannah, whispering that a continent once partitioned by foreign ink is now reclaiming its agency, its voice, and the sacred right to chart its own course across the canvas of history, commerce, and human possibility.

III. Infrastructure as the New Veins of Africa

Infrastructure in Africa is more than concrete and steel; it is the lifeblood of a continent seeking to heal centuries of imposed fragmentation, for roads, railways, ports, and digital networks are not mere physical constructs but extensions of sovereignty, mobility, and ecological flow, and the historical record demonstrates how the lack of integrated infrastructure has repeatedly constrained African potential. From the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, when colonial powers carved Africa with no regard for natural trade corridors, to the railways constructed by the British, French, and Belgians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to extract resources from the interior to the coast—such as the Uganda Railway completed in 1901, connecting Mombasa to Kisumu—these corridors were veins not of life but of extraction, mirroring what biologists today recognize as the disruption of natural ecosystems where migratory routes are blocked and biodiversity suffers; the lesson is clear in physics as well, where the conservation of energy demonstrates that flow must be continuous to avoid dissipation, and in chemistry, where reaction rates slow or stall when catalysts are removed or inhibitors introduced. The Trans-African Highway Network, conceived in the 1970s but formally endorsed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa in 1977, aims to reconnect this broken circulatory system with 56,000 kilometers of planned corridors stretching from Cairo to Cape Town, from Lagos to Mombasa, yet progress remains uneven: while the Cairo–Cape Town route is nearly complete, other corridors such as the Lagos–Abidjan or Dakar–N’Djamena highways remain fragmented, reflecting both political instability and historical legacies of disinvestment, as recorded in archives of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and African Development Bank reports from 1985–2022. Case studies like the LAPSSET Corridor in Kenya, Ethiopia, and South Sudan demonstrate the promise of integrated transport systems, where oil pipelines, ports, highways, and railways converge, while the East African Standard Gauge Railway exemplifies modern engineering ambitions to unify regional economies, reducing transport times from 48 hours to 12 between Nairobi and Mombasa, as reported in the Daily Nation (2018), yet these projects also illustrate the risks of infrastructure divorced from justice, where land disputes, environmental degradation, and local displacement threaten social cohesion, reminding us of the Hindu principle that dharma must govern human activity, and the Bahá’í emphasis on unity and consultation in development. African Traditional Religions contribute insight, as the Igbo proverb states, “He who does not build a path for others will be blocked on his own,” signaling that infrastructure without ethical design undermines the very communities it seeks to serve, and the Swahili saying, “Njia ya mwongo ni fupi” — the liar’s road is short — warns that shortcuts in planning, finance, or governance ultimately lead to collapse. Biblical reflections echo this urgency: Proverbs 16:3 counsels that “Commit your works to the Lord, and your plans will succeed,” emphasizing that technical ingenuity must be inseparable from moral and spiritual foresight. Modern physics and systems theory illuminate the importance of connectivity: in transport networks, efficiency is maximized when nodes are optimally connected, similar to neural networks in the brain or circulatory systems in biology, while chemistry shows that catalysts accelerate reactions without being consumed, illustrating the role of visionary leadership and community engagement as necessary accelerators for African integration. Films like Queen of Katwe (2016) and Lionheart (2018) dramatize how infrastructure—schools, roads, and businesses—transforms lives, connecting opportunity to geography, while songs like Angelique Kidjo’s “Agolo” or Fela Kuti’s “Expensive Shit” remind us that mobility is cultural as well as economic, flowing through music, ritual, and trade. Mathematics, from linear programming to graph theory, underscores the strategic importance of routes: choosing optimal pathways reduces cost, time, and environmental disruption, proving that Africa’s veins are best designed not only for profit but for sustainability, resilience, and justice. Reports from The Guardian (2021) highlight that incomplete or poorly maintained infrastructure costs African economies billions annually, reducing intra-continental trade to less than 18% of total commerce, despite the promise of AfCFTA, while UNCTAD and World Bank studies show that integrated corridors could boost trade by over 20%, lifting millions from poverty while strengthening political cohesion. The convergence of historical archives, engineering studies, biological analogies, physics, chemistry, mathematics, and cultural wisdom teaches a profound lesson: the new map of Africa cannot be drawn solely with ink, for infrastructure is the skeletal, circulatory, and nervous system of sovereignty, a system that must respect ecological rhythms, ethical imperatives, and ancestral knowledge. In practical terms, each railway, highway, and pipeline carries centuries of memory, hundreds of millions of lives, and the ethical responsibility to unify rather than exploit, reminding us that while engineers and policymakers design the material, poets, musicians, prophets, and elders remind us of the spirit; that connectivity is not just physical but moral, cultural, and spiritual; and that the new veins of Africa, if nurtured with justice, knowledge, and foresight, will carry the lifeblood of a continent ready to reclaim its agency, its mobility, and its destiny, singing through every city, village, and savannah the song of a people who will never again be mapped solely by the ink of others.

IV. Mobility Before and After Colonization

Mobility in Africa, before the imprint of colonial borders, was a symphony of human ingenuity, ecological intelligence, and cultural continuity, a rhythm that echoed through the Sahara, Sahel, Congo Basin, and the Great Lakes for millennia, documented in both oral histories and written chronicles: from the caravan routes of the Tuareg and Berber traders connecting Timbuktu, Agadez, and Marrakesh in the 13th century, to the migratory paths of the Maasai across the Rift Valley, to the Luo fishermen navigating Lake Victoria’s intricate waterways, each movement was a carefully calibrated interaction between humans, ecosystems, and spiritual belief, guided by stars, seasonal winds, and the migrations of game, demonstrating an innate understanding of physics, biology, and geometry long before Western science codified these disciplines; the mathematician in the desert or the herder on the savannah calculated trajectories, resource flows, and population capacities in ways that echo modern optimization models, network theory, and systems biology, while chemistry is mirrored in their knowledge of soil fertility, plant cycles, and water purification, and the physics of water currents, wind patterns, and animal migration dictated travel schedules that minimized energy expenditure while maximizing survival and trade efficiency. This mobility was disrupted violently by colonial partition, from the arbitrary lines of the 1884–85 Berlin Conference to the artificial borders imposed by Britain, France, Belgium, and Germany, severing ecosystems, fracturing communities, and immobilizing trade; archives from the British East Africa Protectorate (1900–1920) and Belgian Congo reports detail the forced relocation of pastoralists and miners, the regulation of markets, and the invention of checkpoints that criminalized the age-old circulation of people and goods, while newspapers such as Le Monde (1910–1930) and The Times of London chronicled the imposition of customs duties and passbooks that codified immobility into law. In contemporary terms, only 27 African states offered visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to fellow Africans in 2022, a lingering shadow of partition that constrains labor mobility, education, and regional cohesion, even as initiatives like the Pan-African Passport (adopted by the African Union in 2016) seek to restore freedom of movement, echoing the words of the Yoruba proverb: “A road does not know the boundaries of the village; it only knows where the traveler must go.” Religion, philosophy, and ethics intersect here: the Bhagavad Gita emphasizes dharma as duty, which in mobility can be understood as responsibility to one’s community and environment; Bahá’u’lláh speaks to unity of humankind, envisioning travel and exchange as a moral imperative; the Bible, in Exodus and Acts, underscores the sacred right and sometimes necessity of movement, while Sikh teachings celebrate journeys as both physical and spiritual acts. African Traditional Religions historically encoded migration ethics: the Maasai and Fulani oral histories prescribe seasonal movements, respect for communal grazing lands, and ritual observances that maintain cosmic and ecological balance, demonstrating an indigenous form of environmental science that complements modern ecology and conservation biology. Literature and popular culture memorialize these flows: Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God portrays the tension between imposed structures and indigenous mobility; films like Tsotsi (2005) and The Gods Must Be Crazy (1980) capture movement as survival, cultural expression, and moral negotiation; songs such as Fela Kuti’s “Shakara” and Angelique Kidjo’s “We We” celebrate resilience, migration, and the social pulse of movement. From a scientific perspective, human mobility mirrors fluid dynamics in physics, network efficiency in mathematics, and energy conservation in biology; blocked corridors, whether by walls or bureaucratic inertia, create turbulence, reduce trade flow, and threaten ecological and social stability, as evidenced by UNCTAD reports (2021) and World Bank studies on East and West African transport bottlenecks. Timelines of integration—such as the ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement of Persons (1979), the Southern African Development Community initiatives (1980s–1990s), and AU Agenda 2063—represent ongoing attempts to restore freedom of movement, but historical inertia and political fragmentation still impede the natural rhythms that once allowed pastoralists, merchants, and pilgrims to thrive. In essence, mobility is more than economics; it is cultural memory, spiritual obligation, and ecological wisdom, an interdisciplinary network where physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and ethics converge, and to restore it fully is to honor both ancestors and the living, allowing Africa to move not as a continent divided by arbitrary ink, but as a living organism, humming with commerce, pilgrimage, education, and kinship, reclaiming the pathways once amputated by foreign hands and restoring the ancestral songlines that connect rivers, plains, mountains, and human hearts alike.

V. The Cultural and Spiritual Map

To speak of the cultural and spiritual map of Africa is to recognize that land is not merely soil, minerals, or geopolitical abstraction, but a living covenant, a repository of memory, a witness to human struggle, and a conduit of divine and ancestral presence; precolonial societies understood this in ways that modern science only begins to quantify, from the complex agroecology of the Yoruba, who practiced crop rotation, forest conservation, and sacred groves to maintain biodiversity, to the Akan and Ashanti, whose land tenure systems integrated ritual, law, and economics, ensuring that the chemistry of soil, the biology of pollinators, and the physics of water distribution were respected as part of a moral and spiritual economy, a lesson echoed in the biblical texts of Genesis 1:28 and Leviticus 25, which enjoin humans to steward creation with care, and in the Bhagavad Gita’s vision of dharma, where ethical action governs interaction with the world, and Bahá’u’lláh’s call for unity emphasizes that material progress without spiritual integrity is incomplete. Colonial records, from French West Africa archives (1905–1935) to British Southern Africa reports (1910–1940), document the systematic desecration of sacred sites, the commodification of land, and the dislocation of communities, a rupture mirrored in the visual narratives of films such as Queen of Katwe (2016), which shows how space and geography shape human potential, and Hotel Rwanda (2004), which portrays the tragic consequences of ignoring cultural ties to land in favor of externally imposed borders. Literature, from Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart to Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Wizard of the Crow, illuminates the psychic and cultural violence inflicted when land is reduced to property, revealing that cultural maps are as much ethical as geographical, and songs like Angelique Kidjo’s “Agolo” or Youssou N’Dour’s “Set” celebrate the sacred pulse of place, the rhythms of river and soil, and the invisible lines of community memory. Newspaper reports, including The Guardian (2018) and Daily Nation (2019), highlight modern conflicts over land and sacred spaces, showing that colonial legacies persist in disputes over ownership, extraction, and religious practice, while archaeological archives, such as those from Great Zimbabwe and the Kingdom of Axum, reveal long-standing spatial organization that balanced cosmology, trade, and habitation. Science provides further insight: physics teaches that energy and matter flow along predictable pathways, analogous to sacred and cultural corridors; chemistry demonstrates that disrupting natural cycles alters ecosystems irreversibly; biology confirms that human settlement patterns affect species diversity; and mathematics, through topology and network theory, models how communities interact with space and each other, providing a quantitative framework for understanding the spiritual as well as material map. Chinese philosophies, including Confucian teachings on harmony and spatial ethics, resonate here, emphasizing that human activity must balance with the larger cosmos, while Sikh and Hindu texts underscore the ethical and ritual dimensions of land use, echoing African Traditional Religions in their insistence that sacred spaces are interwoven with human identity and morality. Historical timelines remind us that Africa’s cultural geography has been under constant pressure: the trans-Saharan trade networks (8th–16th centuries) fostered cosmopolitan cities that balanced commerce with ritual; the Atlantic slave trade (16th–19th centuries) violently depopulated regions, breaking spiritual and social linkages; the colonial partition (1884–1914) imposed artificial grids that ignored sacred topography; and post-independence development projects (1960–2020), from dams to highways, often disregarded indigenous cosmologies, a fact documented in UN Habitat reports and World Bank environmental assessments. Films like The Gods Must Be Crazy (1980) dramatize the collision of materialist maps with spiritual landscapes, while music, oral poetry, and theater act as living archives of ecological and cultural knowledge, preserving proverbs such as the Akan’s “The world is a marketplace; the land is home” and the Zulu’s “Umhlaba uyahlala” — the earth endures — reminding us that ethical geography is inseparable from cultural memory. To redraw the map of Africa culturally and spiritually, therefore, requires a multidisciplinary synthesis: historical consciousness, scientific reasoning, ethical reflection, artistic imagination, and spiritual attunement, integrating the findings of physics, biology, chemistry, and mathematics with the rhythms of song, the narrative of literature, the testimony of archives, and the enduring wisdom of traditional religions, so that the land is no longer treated as a commodity, but as covenant, a sacred trust, and a living map of African identity, destiny, and justice, a map that hums with the invisible pathways of ancestors, migratory patterns, ritual observance, and the moral energy that has always guided human settlement and stewardship across the continent, ensuring that Africa’s soil, rivers, forests, and mountains are not merely traversed, measured, or exploited, but honored, remembered, and woven into the ethical cartography of a new and holistic sovereignty.

VI. Drawing With Justice, Not Just Ink

To draw with justice is to recognize that maps are never neutral instruments, for history and archives—from the colonial cartographic records of the British Royal Geographical Society (1880–1910), the Belgian Congo archives (1908–1960), and the French Service Géographique de l’Afrique Occidentale (1905–1935)—reveal how ink and lines were wielded as tools of domination, redistributing land, labor, and life according to foreign interests, while indigenous boundaries, trade routes, and sacred landscapes were effaced or deliberately ignored; newspapers from the 20th century, including Le Monde (1925) and The Times of London (1930), documented disputes over resources and “tribal territories” imposed by colonial decree, reflecting an ethical blindness that the Bhagavad Gita calls attention to in the principle of dharma, emphasizing that action must be righteous, equitable, and mindful of cosmic order, while Bahá’u’lláh insists that unity and justice must underpin all human systems, reminding policymakers that sovereignty without ethics is hollow, and Sikh teachings insist that leadership entails accountability, service, and respect for all beings. Science, too, offers a framework for justice: in physics, systems in equilibrium function harmoniously, while chemical and biological networks demonstrate that disruption in one node propagates imbalance across the entire system, an analogy for Africa’s fractured landscapes, economies, and communities, where roads built without consultation disrupt ecosystems, displace populations, and compromise trade efficiency; mathematics, through graph theory and topology, shows that the shortest, most efficient paths are those that honor connectivity, redundancy, and balance, principles that echo the Swahili proverb, “Njia ya mwongo ni fupi” — the liar’s road is short — warning that shortcuts in ethical design yield failure. Historical case studies reinforce this imperative: the LAPSSET corridor in Kenya, Ethiopia, and South Sudan, while technologically impressive, has sparked disputes over land rights, environmental degradation, and community displacement since its announcement in 2012, documented in both UN Environment Programme reports and Daily Nation coverage, while the Standard Gauge Railway in East Africa highlights how infrastructure, divorced from participatory planning, can reproduce patterns of colonial extraction rather than liberation. African Traditional Religions provide moral insights: the Akan, Yoruba, and Zulu emphasize the sanctity of land, the reciprocity between humans and the environment, and the spiritual obligation to future generations, illustrating that justice in mapping is inseparable from cultural memory, ecological stewardship, and communal consent. Literature and film continue this dialogue: Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Petals of Blood portrays how economic development without justice reproduces inequity and violence; Queen of Katwe (2016) and Lionheart (2018) dramatize the transformative power of ethical infrastructure and opportunity; and songs such as Angelique Kidjo’s “Agolo” and Burna Boy’s “African Giant” insist that cultural vitality and ethical consciousness must accompany material progress. Modern technological and scientific insights reinforce the urgency: network theory demonstrates that trade and communication corridors optimized with equity and redundancy maximize resilience; ecological modeling shows that community-inclusive planning preserves biodiversity; energy flow simulations and chemical reaction analogies teach that efficiency is highest when all nodes are respected and no resource is forced against its nature; and biological principles remind us that social systems thrive when diversity, mobility, and interdependence are maintained. In the global context, historical archives reveal that China’s Belt and Road Initiative (2013–present) offers lessons in both opportunity and risk, where infrastructure development without local ownership or justice can lead to dependency, while Hindu, Bahá’í, and Sikh ethical frameworks converge on the principle that leadership and planning must integrate moral foresight with technical expertise. Justice in mapping, therefore, is a synthesis of law, ethics, science, culture, and spirituality, requiring historians, scientists, policymakers, engineers, religious leaders, and artists to collaborate; to draw with justice is to engage in an act that transcends paper and ink, becoming instead a living ethical framework that recognizes the histories of displacement and exploitation, honors indigenous cosmologies, leverages scientific insights, integrates cultural narratives, and ensures that every line, corridor, and border supports life, prosperity, mobility, and dignity, so that Africa’s new map is not a repetition of colonial impositions but a canvas for sovereignty, equity, and regenerative justice, resonating with the Akan proverb: “He who mismanages the path will stumble,” and embodying the prophetic vision that maps are ethical instruments capable of harmonizing human ambition with ecological integrity, cultural memory, and the spiritual pulse of the continent, where every river, forest, plain, and road is consecrated not only to trade and transit but to justice, conscience, and collective destiny.

VII. Conclusion: The Drumbeat of a New Africa

To conclude the reimagining of Africa’s map is to recognize that the continent’s destiny cannot be confined to ink on paper or lines drawn by foreign hands, for history, archives, and lived experience reveal a complex tapestry where every river, mountain, forest, and desert carries memory, identity, and moral claim: colonial maps from the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, archived in the Royal Geographical Society, illustrate a deliberate fragmentation of peoples and resources, while African oral histories, preserved in griot traditions from Mali to Nigeria, recount centuries of fluid trade, pastoral migration, and pilgrimage that honored ecological rhythms, cultural codes, and spiritual obligations. Literature and film—Achebe’s Arrow of God (1964), Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Wizard of the Crow (2006), Hotel Rwanda (2004), and Queen of Katwe (2016)—capture the human consequences of imposed boundaries, showing how mobility, opportunity, and moral agency are curtailed when maps ignore justice and ancestral wisdom. Songs such as Angelique Kidjo’s “Agolo” (1994) and Fela Kuti’s “Water No Get Enemy” (1975) celebrate the circulation of life, energy, and community, underscoring that infrastructure, commerce, and cultural exchange must harmonize with ethical stewardship. Scriptural and spiritual traditions converge on this ethical vision: the Bible (Proverbs 11:1; Leviticus 25) insists on honesty, stewardship, and covenantal responsibility; Hindu texts emphasize dharma and the consequences of misaligned action; Bahá’u’lláh’s writings demand unity and consultation in governance; Sikh scripture underlines the duty of leaders to act justly; Chinese Confucian philosophy advocates balance between human endeavor and cosmic order; and African Traditional Religions remind us that land, water, and sky are sacred, that disruption of natural and social systems carries spiritual as well as ecological consequences. Scientific principles reinforce this interconnectedness: physics demonstrates that energy flows efficiently through connected systems, biology shows that ecosystems and social systems collapse when corridors are blocked, chemistry reveals that disrupting cycles yields cascading consequences, and mathematics—from graph theory to network optimization—models how trade, communication, and human movement can maximize resilience and equity. Contemporary archives and reports—UNCTAD, World Bank, African Development Bank, and The Guardian (2018–2023)—illustrate the challenges of implementing AfCFTA, the LAPSSET Corridor, and the Standard Gauge Railway, revealing the interplay of infrastructure, governance, corruption, and community engagement, while lessons from China’s Belt and Road Initiative (2013–present) highlight the global stakes of ethical versus exploitative development. Timelines from precolonial trade networks, the trans-Saharan and trans-Atlantic trades, colonial partitions (1884–1960), post-independence integration efforts (ECOWAS 1979; AU Agenda 2063), and modern free trade initiatives demonstrate the persistent struggle to reconcile sovereignty, mobility, and justice. In poetry and philosophy, African proverbs—such as the Akan’s “He who mismanages the path will stumble” and the Swahili, “Haba na haba hujaza kibaba” —little by little fills the measure—remind us that careful, incremental, ethical planning preserves the flow of life, commerce, and culture. The new map of Africa, therefore, is not merely a set of coordinates or borders, but a living, breathing, singing organism, a drumbeat resonating across plains, savannahs, and cities, carrying the wisdom of ancestors, the lessons of science, the imperatives of ethics, and the harmonies of culture, music, and literature; it embodies the integration of human ingenuity and spiritual responsibility, of mathematics and moral philosophy, of physics and ritual, of biology and cosmology, converging to reclaim sovereignty, connectivity, and destiny. The pen and compass are in Africa’s hands, but the ink must be courage, conscience, and cooperative vision; each highway, railway, and border checkpoint is a heartbeat, each school, marketplace, and sacred grove is a node in an intricate ethical network, and each policy, treaty, and trade agreement must honor the sacred covenant between land, people, and future generations, so that the map becomes more than paper—it becomes a hymn, a drumbeat, a living testimony that Africa is reclaiming its agency, its songlines, and its place in the moral, ecological, and spiritual architecture of the world, echoing through time from Timbuktu manuscripts (14th century) to the corridors of modern governance, singing that the continent’s journey is once again guided by justice, unity, and the sacred rhythms of its peoples.

References

Books and Literature

Achebe, C. (1964). Arrow of God. Heinemann.

Achebe, C. (1958). Things Fall Apart. Heinemann.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o. (2006). Wizard of the Crow. London: Vintage International.

Films and Media

Queen of Katwe. (2016). Directed by Mira Nair. Walt Disney Pictures.

Hotel Rwanda. (2004). Directed by Terry George. Lions Gate Entertainment.

Lionheart. (2018). Directed by Genevieve Nnaji. Netflix.

The Gods Must Be Crazy. (1980). Directed by Jamie Uys. Motion Picture International.

Tsotsi. (2005). Directed by Gavin Hood. Sony Pictures Classics.

Newspapers and Periodicals

The Guardian. (2018–2023). Various articles on African trade, infrastructure, and land disputes. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/

Daily Nation. (2018–2020). Reports on East African transport and trade infrastructure. Retrieved from https://www.nation.co.ke/

Le Monde. (1925–1930). Historical coverage of African colonial administration and trade disputes. Retrieved from https://www.lemonde.fr/

The Times of London. (1910–1930). Colonial reports on Africa.

Reports and Institutional Sources

African Development Bank. (2022). African Continental Free Trade Area: Progress and Opportunities. Abidjan: AfDB.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2021). Economic Integration in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. Geneva: UNCTAD.

World Bank. (2022). Africa’s Infrastructure: Development and Integration. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Economic Commission for Africa. (1977). Trans-African Highway Network Master Plan. Addis Ababa: UNECA.

Historical Archives

Royal Geographical Society. (1880–1910). Colonial maps and records of Africa. London: RGS Archives.

Belgian Congo Archives. (1908–1960). Administrative and trade records. Brussels: National Archives of Belgium.

French Service Géographique de l’Afrique Occidentale. (1905–1935). Cartographic records and reports. Paris: Archives Nationales.

Timbuktu Manuscripts. (14th–18th centuries). Historical trade and scholarship records. Mali: Ahmed Baba Institute.

Music and Songs

Kidjo, A. (1994). Agolo [Song]. On Ayé. Mercury/Universal Music.

Kuti, F. (1975). Water No Get Enemy [Song]. On Expensive Shit. Afrobeat Records.

Burna Boy. (2019). African Giant [Album]. Atlantic Records.

Youssou N’Dour. (1990). Set [Song]. On Set. Columbia Records.

Proverbs and Oral Sources

Akan proverb. (n.d.). “The world is a marketplace; the land is home.” Retrieved from African proverb collections.

Swahili proverb. (n.d.). “Njia ya mwongo ni fupi.” Retrieved from African proverb collections.

Zulu proverb. (n.d.). “Umhlaba uyahlala.” Retrieved from African proverb collections.

Yoruba proverb. (n.d.). “A road does not know the boundaries of the village; it only knows where the traveler must go.” Retrieved from African proverb collections.

Scripture and Religious Texts

Bible. (2011). English Standard Version. Crossway.

Bhagavad Gita. (2012). Swami Sivananda (Trans.). Divine Life Society.

Bahá’u’lláh. (1993). The Hidden Words. Bahá’í Publishing Trust.

Guru Granth Sahib. (2003). Sikh Religious Text. Sikh Missionary Society.

Confucius. (1998). The Analects (E. Slingerland, Trans.). Hackett Publishing.

Scientific References

UN Habitat. (2019). Sustainable Urban Mobility in Africa. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

Graph Theory and Network Analysis: Bondy, J. A., & Murty, U. S. R. (2008). Graph Theory. Springer.

Systems Biology and Ecology: Kitano, H. (2002). Systems Biology: A Brief Overview. Science, 295(5560), 1662–1664.

Transport Physics and Optimization: Ceder, A. (2007). Public Transit Planning and Operation: Theory, Modeling, and Practice. Elsevier.

Global Infrastructure References

China Belt and Road Initiative. (2013–present). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Retrieved from https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/

LAPSSET Corridor Project. (2012–2023). Kenya Ministry of Transport Reports.