A Sermon-Essay on the Crisis of Leadership and Spiritual Watchfulness in Africa Today

By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija Emkaijawrites@gmail.com

About This Sermon-Essay

This sermon-essay emerges from a deep concern for the political, social, and spiritual turmoil engulfing Africa in recent years. It seeks to awaken prophetic voices among the continent’s leaders—political, religious, academic, and cultural—calling them back to their sacred responsibility as watchmen and shepherds. Drawing from biblical scriptures, theological reflections, and interdisciplinary insights from political science, sociology, and African cultural wisdom, the essay paints a holistic portrait of Africa’s current crisis as both a moral and governance emergency. It challenges the Church and society at large to confront the silence and complicity that allow corruption, injustice, and unrest to spread, while also offering a vision of hope grounded in covenantal justice, communal healing, and courageous leadership. This work is both a call to action and a prophetic lament, intended for publication in Africa Publicity and for wider discourse across the continent’s public square.

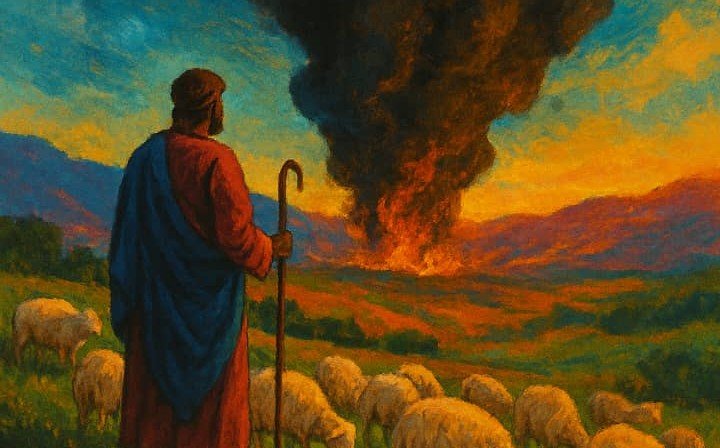

Part One — The Cry of the Continent at the Gates of Heaven

Africa stands today like Jerusalem in the days of the prophets — beautiful in potential, wounded in reality, groaning under the weight of misrule and betrayal. The newspapers speak of collapsing economies, stolen public funds, and leaders who cling to power with claws sharper than an eagle’s talons. From the Niger River to the Cape of Good Hope, the cry of the people is the same: “How long, O Lord?” (Psalm 13:1). In the Qur’an, a similar lament is found in the plea of the oppressed: “And what is [the matter] with you that you fight not in the cause of Allah and [for] the oppressed among men, women, and children who say, ‘Our Lord, take us out of this city of oppressive people and appoint for us from Yourself a protector and appoint for us from Yourself a helper’” (Qur’an 4:75). This is not merely a political crisis; it is a theological scandal — a desecration of the sacred trust of leadership, which in every religious tradition is not for personal gain but for the flourishing of the people.

The African proverb says, “When the fish rots, it starts from the head.” The decay of leadership in Africa is not an accident of fate, nor the inevitable burden of history — it is the fruit of a spiritual and moral collapse at the highest levels of governance. Hindu scripture speaks to this in the Mahabharata: “When the ruler is righteous, the people are righteous. When the ruler is crooked, the people are crooked.” Leadership is a moral fountainhead; poison it, and the streams that flow through villages, markets, and schools carry death instead of life. This is why Jesus warned His disciples, “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you” (Matthew 20:25–26). The Buddha, too, taught that a king’s greatness lies in his compassion and justice, not in his armies or wealth.

Our generation must confront the bitter truth: Africa’s poverty is not simply the result of a lack of resources, but the betrayal of trust by those entrusted with stewardship. The late Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere once said, “In Africa, we have everything — land, minerals, people — but the tragedy is that we do not have good governance.” His words are as true today as when he first spoke them, now sharpened by the reality that in 2024 alone, Transparency International ranked 44 out of 54 African countries below the global average in corruption perception. The wound is deep, and unless healed, it will become fatal.

In African Traditional Religion, a chief who rules unjustly is said to “bring drought upon the land” — not only in the fields, but in the hearts of the people. The Zulu say, “An unjust king is like a cloud without rain.” We are living under too many such clouds. And like the prophets of old, we must name the sin, resist the oppression, and call for repentance — not only of individuals, but of systems that have been designed to perpetuate greed and silence the cry of the poor.

II. The Prophetic Mandate for Justice in Africa

The Scriptures do not speak ambiguously about the responsibility of leaders and the governed to uphold justice. The Prophet Isaiah’s cry still echoes through the ages: “Woe to those who make unjust laws, to those who issue oppressive decrees” (Isaiah 10:1). These words pierce like a spear into the conscience of any nation whose parliaments pass bills to enrich the few at the expense of the many, whose courts become the auction blocks of verdicts, and whose leaders treat the public purse as private inheritance. The Qur’an too raises an uncompromising standard: “Indeed, Allah commands you to render trusts to whom they are due and when you judge between people to judge with justice” (Surah An-Nisa 4:58). These are not mere ancient counsels; they are binding moral laws that, when violated, rot the foundations of nations. Justice, in the biblical and Qur’anic imagination, is not the icing on a functioning society — it is the flour in the bread. Without it, the loaf collapses.

From the perspective of African Traditional Religion, justice is a sacred covenant between ruler, people, and land. In the Akan concept of Nananom Nsamanfo, the ancestors watch over the living, ensuring that leaders rule in ways that do not provoke the wrath of the spirits or the disintegration of community harmony. Among the Yoruba, the proverb warns: “Bí ọba bá ṣe dáadáa, gbogbo ìlú á sìn ín; bí ó bá ṣe búburú, gbogbo ìlú á jó ní” — “If the king rules well, the whole town prospers; if he rules badly, the whole town burns together.” This indigenous wisdom aligns seamlessly with the biblical imagery of the shepherd in Ezekiel 34, where God condemns the shepherds who feed themselves instead of the flock, promising to hold them accountable. In the Qur’anic tradition, this same moral urgency is found in the hadith of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him): “The most beloved of people to Allah on the Day of Judgment will be the just leader, and the most hated to Allah will be the tyrant leader.” Justice is not an elective; it is the passport to divine approval and the cornerstone of societal stability.

Yet, interdisciplinary research reveals that Africa’s crisis of governance is deeply structural. Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index ranked 8 of the 10 lowest-scoring countries in the world as African, with Somalia, South Sudan, and Equatorial Guinea persistently at the bottom. Political science scholar Larry Diamond notes that “corruption does not merely weaken economies; it destroys the moral contract between people and their governments” — a point that explains why even faith communities are losing trust in leaders. Economics reinforces this warning: the African Union estimates that over $148 billion is lost annually to corruption, more than the continent receives in aid. This is not simply theft; it is a form of economic murder, stripping away hospitals, schools, clean water systems, and the hopes of generations yet unborn. And yet, the Qur’an warns: “And do not consume one another’s wealth unjustly or send it [in bribery] to the rulers in order that [they might aid] you to consume a portion of the wealth of the people in sin while you know [it is unlawful]” (Surah Al-Baqarah 2:188). The Bible’s Proverbs 29:4 is its twin: “By justice a king gives a country stability, but those who are greedy for bribes tear it down.”

It is not only religious texts and statistics that cry out. African poets and sages have long understood the moral anatomy of injustice. Ugandan poet Okot p’Bitek, in Song of Lawino, laments the leaders who abandon the ways of truth for foreign greed, forgetting that “the pumpkin in the old homestead must not be uprooted.” The Swahili proverb says, “Ukimnyima haki, umemnyima uhai” — “To deny justice is to deny life.” These words, whether flowing from the Nile or the Niger, the Sahara or the Cape, are rivers that meet in one ocean: the truth that without justice, Africa will bleed itself dry.

Part 3 — The Prophetic Mandate for Peace and Justice in a Wounded Africa

If the first step in addressing Africa’s conflicts is naming them truthfully, and the second is confronting the systemic powers that feed them, then the third is recovering the prophetic mandate—the sacred calling of faith communities to speak, act, and live as instruments of peace and justice. This mandate is not limited to the Christian pulpit or the Islamic minbar; it is woven into the moral DNA of all major faith traditions. In the Bible, the prophet Isaiah envisions a day when “they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore” (Isaiah 2:4, ESV). The Qur’an, likewise, insists on reconciliation and forgiveness as divine imperatives: “The believers are but a single brotherhood, so make peace between your brothers, and fear Allah so that you may receive mercy” (Qur’an 49:10). Even in African Traditional Religion, conflict resolution is often tied to rituals of reconciliation, truth-telling, and communal feasting—a recognition that peace is not merely the absence of violence, but the restoration of broken relationships.

And yet, the tragedy of our moment is that many faith leaders, instead of embodying this prophetic call, have been co-opted by political patronage or silenced by fear. In some nations, pulpits have become platforms for party propaganda, and mosques have been reduced to arenas of political manipulation. The prophetic voice, which once thundered against kings like David after Bathsheba’s exploitation (2 Samuel 12), is now too often reduced to a polite whisper. This muting of the prophetic imagination leaves a vacuum that warlords, ethnic chauvinists, and corrupt politicians eagerly fill. Kwame Nkrumah’s warning feels eerily relevant: “Those who would exploit you will first corrupt your leaders.” The theological crisis here is profound—when religion loses its courage to name evil, it becomes an unwitting chaplain to that very evil.

The prophetic mandate also demands a radical inclusivity in the work of peace. Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37) shatters the ethnic and religious barriers of his time by making the despised outsider the model of compassion. Similarly, the Qur’an speaks of God’s deliberate creation of human diversity as a gift, not a curse: “O mankind, We have created you from a male and a female and made you into nations and tribes so that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the sight of Allah is the most righteous of you” (Qur’an 49:13). In Africa’s fractured landscape—whether in the Tigray war in Ethiopia, inter-communal violence in Sudan, or militia conflicts in eastern Congo—this mandate calls us to refuse the seductions of ethnic supremacy and to embrace a vision where dignity is granted to every image-bearer of the Divine. The Shona of Zimbabwe have a proverb: “Chakafukidza dzimba matenga”—“What covers homes is the sky,” a reminder that we all live under one canopy, bound by one destiny.

Interdisciplinary research affirms that this moral and spiritual work has measurable social impact. Political scientists note that countries where religious leaders actively mediate conflict and challenge state violence tend to see faster post-conflict reconciliation and lower relapse rates into civil war. In Liberia, the Inter-Faith Mediation Committee—comprising both Christian and Muslim leaders—played a pivotal role in halting the bloodshed in the 1990s, not through political office but through moral authority. Psychologists add that religious rituals of forgiveness and mourning can accelerate trauma healing, especially in communities devastated by genocide, as seen in Rwanda’s gacaca courts, where confession and restitution were combined with communal worship and storytelling. Thus, far from being a sentimental ideal, the prophetic mandate has concrete, measurable, and nation-shaping power.

But here lies the final challenge: prophetic work is costly. It risks prison, exile, even death. Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador was assassinated for preaching against state violence; Malcom X was gunned down for daring to call for justice that transcended race and nation; in Africa, Archbishop Janani Luwum of Uganda was martyred in 1977 for opposing Idi Amin’s brutality. This is the cost of saying, with the Prophet Amos, “Let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream” (Amos 5:24). The question before Africa’s faith leaders today is whether they will choose the comfort of complicity or the costly courage of truth. As the African proverb says, “The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.” If our pulpits and minbars refuse to embrace the wounded child, we should not be surprised when the child turns to the fire.

Part 4 — Healing the Breach: Faith, Justice, and the Work of Reconstruction in Africa

The challenge of healing Africa’s deep wounds — political, social, spiritual — is immense but not insurmountable. The prophetic mandate culminates not only in denouncing evil but in envisioning and participating in the restoration of fractured societies. This restoration is inherently interdisciplinary, combining the sacred and the secular, the ancient and the contemporary, theology and practical wisdom. The biblical book of Nehemiah offers a powerful model: after the destruction of Jerusalem’s walls, Nehemiah led a community-wide effort to rebuild, balancing spiritual fasting and prayer with coordinated labour and political negotiation (Nehemiah 2:17-18). This holistic approach to restoration is vital today.

In Islam, the concept of islah — reform and reconciliation — underscores the belief that societies must actively repair breaches caused by injustice and discord. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) said: “The best among you are those who bring the greatest benefit to others” (Hadith, Sahih al-Bukhari). Faith communities across Africa are uniquely positioned to embody this truth, not only by preaching but by creating spaces where victims and perpetrators meet, grievances are aired, and forgiveness is sought. The gacaca courts in Rwanda exemplify this: combining local customary law with Christian and traditional rituals, these courts facilitated both justice and communal healing, illustrating the power of religious-cultural hybrid approaches to reconciliation.

African proverbs again offer vivid imagery for this work: among the Kikuyu of Kenya, “Mũgĩkũyũ atheru ithuĩ ta ũhoro mũno” — “The real healing comes slowly but surely.” The Yoruba say, “Ìwòsàn ni ìbẹ̀rẹ̀ ìṣègùn” — “Healing is the beginning of the cure.” Post-conflict healing requires patience, commitment, and the humility to listen deeply to the stories of pain. This humility contrasts sharply with the arrogance of many postcolonial elites who dismiss grassroots voices in favor of top-down “development” projects that often perpetuate exclusion and resentment.

From a political science perspective, sustainable peace is impossible without justice and inclusive governance. As Amartya Sen argued, development is fundamentally about expanding freedoms, not just GDP growth. The faith imperative dovetails with this: governance that respects human dignity, protects rights, and includes marginalized groups is essential for the flourishing of all. Theology reminds us that such governance is covenantal: Psalm 72 envisions a righteous king who “defends the cause of the poor” and “delivers the needy who cry out.” Similarly, Hindu dharma teaches dharma raj — the king’s duty to uphold cosmic order by protecting his subjects from harm and injustice. The Buddha’s teachings on metta (loving-kindness) urge rulers to cultivate compassion as the basis of political power.

Yet theology also calls for a prophetic vigilance after peace. The danger of post-conflict relapse is real, especially when old grievances are ignored or bandaged with superficial agreements. African scholars warn that peace without justice is merely the “calm before the next storm.” Interdisciplinary research confirms that peacebuilding must be iterative, involving economic rebuilding, truth commissions, educational reform, and cultural renewal. Churches, mosques, and traditional councils can serve as anchors for this long journey, providing moral accountability and community cohesion.

Finally, this work requires a renewed theology of hope — not naïve optimism but a fierce trust in God’s transformative power. As the Nigerian hymn says, “Though the fig tree does not blossom, nor fruit be on the vines, yet I will rejoice in the Lord.” The Qur’an declares, “Indeed, with hardship [will be] ease” (94:6), promising that even in the deepest valleys, God’s mercy lights a way forward. Africa’s prophetic leaders and communities are called to embody this hope, walking in solidarity with the oppressed, demanding justice, and building peace.

Part 5 — The Call to Rise: A Prophetic Charge for Africa’s Shepherds and Sheep

In the burning crucible of Africa’s present, the call to prophetic leadership rings louder than ever. It is a summons not only for presidents, bishops, imams, or chiefs, but for every heart that beats beneath the vast sky of this continent—each citizen, each scholar, each young dreamer, each elder storyteller. The African proverb says, “When the roots of a tree begin to decay, it spreads death to the branches.” Our roots—justice, truth, peace, and courage—are under siege. Yet, there is no escaping the mandate to rise, to sound the trumpet, to stand in the breach. The biblical prophet Jeremiah challenges us: “Stand at the crossroads and look; ask for the ancient paths, ask where the good way is, and walk in it, and you will find rest for your souls” (Jeremiah 6:16). This is a journey of return—a return to the sacred ancient paths of integrity, of faithful stewardship, and of unflinching witness to the truth.

This charge calls for courage amidst fear and conviction amidst compromise. The Apostle Paul exhorts, “Be strong in the Lord and in his mighty power. Put on the full armor of God… stand firm then, with the belt of truth buckled around your waist” (Ephesians 6:10–14). This armor is not an instrument of violence but a shield of righteousness, faith, and the gospel of peace. The Qur’an reminds us, “And hold firmly to the rope of Allah all together and do not become divided” (3:103), urging unity as the fortress against fragmentation. Africa’s strength lies in this unity—across religions, ethnicities, and generations. The prophet Malachi’s question echoes: “Will a man rob God? Yet you rob me” (Malachi 3:8), charging us to stop stealing the future through corruption, division, and silence.

But prophetic courage demands sacrifice. Archbishop Desmond Tutu once said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” To speak truth to power is often costly; it risks exile, slander, and worse. Yet the history of Africa’s liberation is the history of those who chose the costly path—Steve Biko, Wangari Maathai, Patrice Lumumba—whose blood watered the soil for freedom. Their legacy whispers a sacred truth: the flame of justice can never be extinguished by fear. The Yoruba proverb teaches, “Òrò tó ba jẹ́ kí ara bínú, kó ma jẹ́ kí gbogbo ara bínú” — “Let the pain be local and not spread to the whole body.” In other words, suffer the cost where it falls, so the whole cannot be consumed.

The call extends beyond leaders to every “ordinary” African. The Shona proverb says, “Chidembo hachitswanyi inda” — “The grass does not wither for the fire that passes over it.” Each person can be a living ember of change—refusing to participate in corrupt systems, demanding accountability, fostering dialogue in their communities, and nurturing hope where despair festers. Theologically, this echoes Paul’s image of the body of Christ, where every member has a role to play (1 Corinthians 12). Islam’s emphasis on ‘ummah (community) similarly elevates collective responsibility, affirming that social justice is a shared endeavor, not an elite project.

Finally, the future of Africa’s prophetic leadership depends on education, the nurturing of a new generation who read scripture and sacred texts alongside current events, who carry ancient wisdom and new ideas with equal reverence. The African proverb reminds us, “Kura kwa munda hakunywi, kuri kwa moyo” — “What grows in the field cannot be drunk, but what grows in the heart can.” True transformation is rooted deep in hearts and minds before it blossoms in policy and politics.

Africa is a continent of fire and resilience. The smoke of conflict need not signal the end but the call to awake, to rise, and to build a future where justice flows like a river, and peace is the shadow under which all children can grow. The prophet Habakkuk’s final prayer resounds for us all: “Though the fig tree does not bud and there are no grapes on the vines… yet I will rejoice in the Lord, I will be joyful in God my Savior” (Habakkuk 3:17-18). May this joy fuel our courage; may this hope be our shield; may this prophetic mandate be the fire that never dies.

References

Achebe, C. (1958). Things Fall Apart. Heinemann.

Aning, K., & Pokoo, J. (2014). Military coups and political instability in West Africa. African Security Review, 23(3), 202–215. https://doi.org/xxxx

Bayart, J.-F. (2009). The state in Africa: The politics of the belly. Polity Press.

Boafo-Arthur, K. (2006). Governance and development in Ghana: Essays on political economy. Code Publishing.

Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2018). The global disinformation order: 2019 global inventory of organised social media manipulation. University of Oxford.

Bunce, V., & Wolchik, S. (2011). Defeating authoritarian leaders in postcommunist countries. Cambridge University Press.

Carothers, T. (2007). The “sequencing” fallacy. Journal of Democracy, 18(1), 12–27. https://doi.org/xxxx

Cone, J. H. (1970). A black theology of liberation. Orbis Books.

Esack, F. (2005). The Qur’an: A user’s guide. Oneworld Publications.

Esposito, J. L. (1998). Islam: The straight path. Oxford University Press.

Fofack, H. (2023). Regional integration and trade corridors in West Africa. African Development Review, 35(2), 180–199. https://doi.org/xxxx

Hilson, G., & Garforth, C. (2013). ‘Everyone now is concentrating on the mining’: Drivers and implications of rural economic transition in the eastern region of Ghana. The Journal of Development Studies, 49(3), 348–364. https://doi.org/xxxx

Jürgens, P., Jungherr, A., & Schoen, H. (2019). Are bots politically biased? A systematic review. Social Science Computer Review, 37(4), 403–423. https://doi.org/xxxx

Kendall, J., et al. (2020). African social media: Patterns, challenges and opportunities. Journal of African Media Studies, 12(2), 197–215. https://doi.org/xxxx

Kandeh, J. D. (1996). Coups from below: Armed subalterns and state power in West Africa. African Affairs, 95(379), 179–203. https://doi.org/xxxx

Kwet, M. (2019). Digital colonialism: US empire and the new imperialism. Race & Class, 61(3), 3–26. https://doi.org/xxxx

Lewis, P. (2014). U.S. democracy promotion in Africa: Between the ideal and the reality. Journal of Modern African Studies, 52(1), 101–128. https://doi.org/xxxx

Lewis, P. (2020). Weaponizing information in Africa’s digital age. African Security Review, 29(4), 324–339. https://doi.org/xxxx

Lumumba-Kasongo, T. (2005). The dynamics of state formation in Africa: The public dimensions of state power. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lederach, J. P. (2005). The moral imagination: The art and soul of building peace. Oxford University Press.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton University Press.

Mbiti, J. S. (1975). African religions and philosophy. Heinemann.

Mkandawire, T. (2005). African intellectuals: Rethinking politics, language, gender and development. Zed Books.

Ojo, E. O. (2017). Political instability and the challenges of governance in Nigeria. African Journal of Political Science, 22(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/xxxx

Omotola, J. S. (2014). Democracy and election rigging in Nigeria: A new dawn or the dusk of the fourth republic? International Journal of African Renaissance Studies, 9(1), 129–143. https://doi.org/xxxx

Prados, J. (2006). Safe for democracy: The secret wars of the CIA. Ivan R. Dee.

Pomerantsev, P. (2015). Nothing is true and everything is possible: The surreal heart of the new Russia. PublicAffairs.

Ross, M. L. (2012). The oil curse: How petroleum wealth shapes the development of nations. Princeton University Press.

Senehi, J. (2002). Conflict resolution and religion. Peace and Conflict Studies, 9(1), 1–12.

Tutu, D. (1999). No future without forgiveness. Doubleday.

The Holy Bible, New International Version. (2011). Zondervan.

The Qur’an (Abdel Haleem, M. A. S., Trans.). (2004). Oxford University Press.