By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija— Emkaijawrites@gmail.com

PART I — THE DRUMBEAT BEFORE THE DAWN

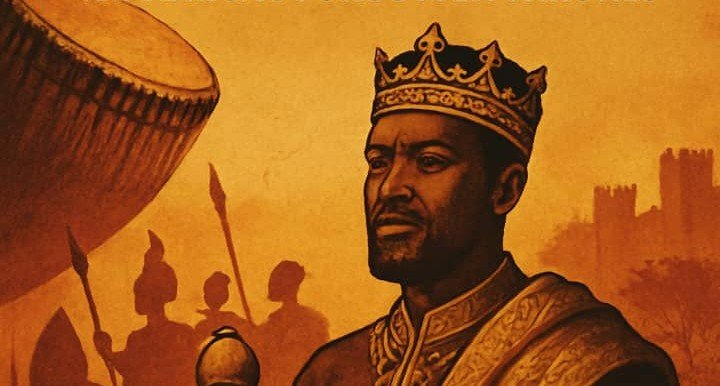

“When the drums are silent, the ancestors weep.” — Proverb from Western Uganda. The Kingdom of Tooro was never a tombstone in Africa’s graveyard of lost empires. It is a drum, a living beat that outlived the silence imposed by colonial erasure, political abolition, and the modern temptation of forgetting. Its story begins not in the dust of defeat but in the fire of self-assertion. Tooro was born in 1830, in the shadow of the mighty Bunyoro-Kitara Empire, when Prince Kaboyo Olimi, son of Omukama Nyamutukura Kyebambe III, sought autonomy and cultural clarity amidst the fragmentation of the time. He was not merely rebelling—he was redefining the map of dignity. This was a moment of African political creativity, a reminder that even before European borders carved the continent like meat, Africans were drawing their own boundaries with vision, power, and spiritual purpose.

Kaboyo’s founding of Tooro was not a betrayal of his father but a profound act of spiritual inheritance: he took the ancestral fire and kindled it anew. In African political philosophy, authority is not always centralized—it flows like a river, branching where necessary to sustain life. The Banyoro proverb says, “Omuzi ogw’omuti gumera aho gwaguhiikira” — “The root of a tree grows where it is planted.” Tooro grew where it was planted, rooted in Bunyoro’s soil but flowering with its own fragrance. It established its own royal court, linguistic purity, spiritual rites, and regal architecture, demonstrating the adaptive strength of African monarchies.

Yet like many African thrones, Tooro would not be spared the cold steel of colonialism. The British, enchanted by the mountain breezes but threatened by the drumbeats of autonomy, encroached upon the kingdom’s sovereignty. Through treaties, manipulation, and indirect rule, Tooro was folded into the larger British Protectorate of Uganda by the early 20th century. But the kingdom was never fully swallowed. The British used the cultural capital of Tooro’s monarchy to legitimize their rule, yet they never understood that the throne’s real power did not sit in the palace—it resided in the people’s tongues, their rituals, their reverence for Empaako, and their ancestral memory.

This memory was tested during Uganda’s post-independence turbulence. In 1967, under Milton Obote’s constitutional reforms, all traditional kingdoms were abolished—cast aside as “feudal relics” incompatible with the modern state^4. The royal drums were silenced by law. Tooro’s palace was stripped of its powers, its royal symbols scattered like ashes, its Omukama forced into political exile. But the abolition did not erase the kingdom—it only drove it into the sacred interior of the people. As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o reminds us in Decolonising the Mind, colonial and postcolonial authorities alike have long feared the rootedness of indigenous memory, which speaks in idioms, dreams, and drums.

Yet, Tooro, like many African kingdoms, was not content to stay buried. In the early 1990s, after the political winds shifted, the drums were brought back to life. The 1993 Traditional Rulers (Restitution of Assets and Properties) Statute^6, followed by Article 246 of the 1995 Ugandan Constitution, restored the cultural institutions of Uganda. In September 1993, a new Omukama, Patrick David Matthew Kaboyo Olimi III, was enthroned, bearing not just a crown but the spiritual burden of awakening a sleeping soul.

Tooro rose, not as a political kingdom but as a cultural and spiritual kingdom—one whose survival speaks to Africa’s enduring belief in the sacredness of origin. In many African cosmologies, death is not an end but a crossing; and so it was with Tooro—crossing from political death into cultural resurrection. Even now, the people speak Rutooro, whisper Empaako blessings, gather for the Empango coronation festival, and bow their heads when the royal drums beat.

Ali Mazrui, in his seminal work The Africans: A Triple Heritage, argued that African identity rests on the uneasy triangle of indigenous traditions, Islamic influences, and Western impositions^8. Tooro teaches us that the indigenous is not a fading memory, but a pillar still holding the continent upright. Where others see kingdoms as museums, Tooro invites us to see them as universities of wisdom, guardians of language, and sanctuaries of ancestral rhythm.

So when young people dance at Empango with both smartphones and ankle bells; when elders offer Empaako names beside modern birth certificates; when the Omukama receives his people with both majesty and humility—something ancient breathes. Tooro lives.

As the Rwenzori Mountains keep their silent vigil over the kingdom’s hills, the people remember:

“Omugisa gumwita owutamanya.” — Blessings kill the one who does not understand them. Tooro, once misunderstood as a feudal relic, now rises as a blessing reclaimed—a call to Africa to re-understand itself.

PART II — THE RISE OF TOORO AND ITS LONG WAR WITH EMPIRE

“The wind may uproot the tree, but not the rock beneath.” — Batooro proverb. In the early 19th century, Africa was still a continent of sovereign imagination. Empires breathed in the pulse of the land—organically forged by ancestors, not fabricated in foreign chanceries. Tooro’s emergence in 1830 was one such moment of internal recalibration, a break not from tradition but toward renewal. Kaboyo Olimi I, the visionary prince of Bunyoro-Kitara, was not exiled by rebellion alone—he was chosen by historical necessity. The Bunyoro kingdom, once the unrivaled citadel of the Great Lakes region, was fragmenting under internal strain and external threats. Kaboyo’s move southward to found Tooro was, in essence, the replanting of a sacred seed.

From its earliest days, Tooro wielded the twin instruments of African sovereignty—language and land. Rutooro was not merely a dialect of Runyoro—it became a vessel for cultural distinction, a theological lexicon for the sacredness of kingship, and a medium for oral memory. The land, stretching from the Rwenzori slopes to the Semliki valley, was consecrated through shrines, clan totems, and agricultural rituals. Even before Europeans saw it as a resource to extract, the people of Tooro knew it as a covenant to be preserved.

But the colonial tide soon reached Tooro’s borders. By the late 19th century, British imperial eyes, hungry for strategic advantage in the Nile basin, cast their gaze upon the western kingdoms of Uganda. Tooro, despite its relative youth, was seen as a geopolitical jewel. The Berlin Conference of 1884–85 had carved Africa into colonial appetites, and the British, through both treaty and treachery, were ready to swallow entire polities. In 1894, Uganda was officially declared a British Protectorate, and Tooro—alongside Buganda, Bunyoro, and Ankole—was folded into this imperial fiction.

Unlike Buganda, which negotiated power through strategic compliance, or Bunyoro, which suffered outright military suppression, Tooro was absorbed through diplomatic illusion. British administrators like Sir Harry Johnston engaged in “indirect rule,” appointing local chiefs, co-opting royal authority, and reducing the Omukama’s power to ceremonial gestures. This was not governance—it was colonial choreography, masking domination behind African faces. The British justified this arrangement through the myth of “tribal inferiority,” painting Tooro’s cultural systems as inferior to British rationality. But the people remembered.

Indeed, the drumbeat of defiance continued, not always through open rebellion, but through cultural resistance. Tooro’s people preserved Rutooro in liturgy and song. They passed down clan genealogies, conducted royal initiation rites in secret, and offered Empaako blessings even under the shadow of the Union Jack. As Achille Mbembe writes in On the Postcolony, African subjects under colonialism practiced “surreptitious sovereignty”—they learned to wear the mask of submission while guarding the soul of rebellion.

But colonialism did more than exploit—it fractured memory. Missionary education systems introduced English and biblical names, often discouraging the use of Empaako or clan identity. Land was surveyed and reclassified, breaking ancestral ties to sacred forests and burial grounds. Young Tooro men were conscripted into the King’s African Rifles, fighting for an empire that stole their soil. Women were lured or forced into domestic labor in European homes, while missionaries labeled indigenous knowledge systems—especially herbal medicine and divination—as “witchcraft”.

Tooro, like many African kingdoms, found itself hollowed out—its throne polished but powerless, its rituals performed but surveilled. Yet the people refused to forget. The royal household quietly kept alive the rituals of Empango (the coronation anniversary), and even after Omukama George David Kamurasi Rukidi III was reduced to a ceremonial figure, the cultural memory of his authority remained intact.

Tooro’s colonial subjugation was, in essence, a theft of voice. But the voice, though stifled, never ceased. Valentin-Yves Mudimbe’s theory of the “colonial library” teaches us that African knowledges were buried, not burned—that colonialism attempted to replace African epistemologies with European systems but failed to erase the indigenous archive encoded in oral tradition, gesture, and rhythm.

Even as colonial schools taught English hymns, children in Tooro still learned ancestral songs. Even as the British redrew clan territories, elders remembered the sacred trees that marked land inheritance. Resistance, here, was not always revolt—it was remembrance.

By the time Uganda achieved independence in 1962, Tooro had endured decades of cultural slow bleeding. But it still stood. However, independence brought another blow. In 1967, President Milton Obote’s new republican constitution abolished all kingdoms in Uganda. The cultural institutions that had survived colonialism were now declared illegal under African nationalism. Omukama Patrick Kaboyo Olimi II was stripped of his throne. The royal drums were silenced once again—not by the colonizer, but by the African state.

Yet even then, Tooro did not die. In the secrecy of homes, rituals continued. In names, stories, and sacred greetings, the kingdom endured. In truth, Tooro’s greatest act of resistance was its refusal to vanish. As the Ashanti proverb reminds us: “No matter how long the night, the day will break.”

PART III — LANGUAGE, LAND, AND THE SOUL OF RUTOORO

“Amaizi g’ekiro tagibwa mu ntamu” — The water of the night cannot be carried in a clay pot. This Batooro proverb reminds us that some things—like language and land—are too sacred to be carried by fragile vessels. They must live in memory, in soil, in spirit. If the Omukama is the heart of Tooro, then Rutooro is its breath, and the land its bones. Together, they form the trinity of identity: speech, soil, and sovereignty. When colonial powers dismissed African languages as “vernaculars” and subdivided land like stolen cake, they underestimated the metaphysical depth of what they were touching. In Tooro, language is not simply a tool—it is a shrine. And the land is not simply territory—it is the skin of the ancestors.

1.Language as Ancestral Spirit

Rutooro, spoken by an estimated 700,000 people^1, is part of the larger Runyakitara cluster, a Bantu linguistic family that includes Runyoro, Runyankore, and Rukiga. But Rutooro is more than its syntax or grammar—it is a living archive of kingship, kinship, and cosmology. The Empaako naming system, for instance, is uniquely Tooro and Bunyoro—an affectionate and spiritual salutation practice where individuals are given one of twelve sacred names, such as Amooti, Abooki, or Araali. This naming system is not decorative—it is ontological. To greet someone using their Empaako is to acknowledge their divine humanity. It was recognized by UNESCO in 2013 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Colonial administrators found this system puzzling. Missionaries tried to replace Empaako with Christian names, and colonial schools punished children for speaking Rutooro^4. Yet the language persisted—not just in homes, but in the marketplace, in song, in lullabies. In oral literature, orugambo (proverbial speech) was used to teach diplomacy, respect, and power. Proverbs such as “Enyama ey’omurokore eihurirwa aha mwenge”—“The meat of the poor man is chewed in beer discussions”—capture the dignity and irony of daily life. In this way, Rutooro became a form of soft resistance: a language that refused to die, even in the presence of English domination.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, in Decolonising the Mind (1986), warned that the suppression of African languages was “the most effective weapon in cultural subjugation.”^5 Rutooro survived precisely because the Batooro understood that to forget their tongue was to forfeit their future.

2.Land as Covenant

The Kingdom of Tooro stretches across fertile hills, sacred forests, and the majestic Rwenzori ranges. But this land is not neutral. It is sacred space—a living altar. Before colonialism, land in Tooro was organized around clan stewardship. Every clan had spiritual and social responsibilities over forests, rivers, and farmland. Sacred sites—such as the Mubende Hill and the Amabere ga Nyinamwiru caves—were used for ritual, rain-making, and storytelling. These were not superstitions; they were sacred technologies of environmental balance and cultural continuity.

But British colonial rule introduced land alienation through formal surveys and Crown Land Ordinances. Vast areas were reclassified as Crown property, wildlife reserves, or missionary zones, and native spiritual sites were displaced. The 1900 Uganda Agreement between the British and the Buganda Kingdom, though focused on Buganda, became a precedent that enabled massive land alienation across Tooro and other kingdoms^7. Tooro’s royal lands, including burial sites and sacred forests, were reduced or taken without consultation. Some lands were given to Christian missions, especially Anglican institutions, who sometimes collaborated with colonial officials to undermine indigenous land tenure.

Yet the land remembers. The people continued to plant emikuka (sacred groves), and to bury their dead facing the Rwenzori, as a way of anchoring the spirit to the mountains. The Rwenzori themselves—known as the “Mountains of the Moon”—were never merely geographical features. To the Batooro, they are the abode of the gods. As one elder once said, “When the Rwenzori is hidden in mist, the ancestors are whispering.”

The Rwenzururu movement of the 1960s, which emerged among the Bakonzo people of the Rwenzori area (formerly part of Tooro), illustrates how deeply tied land and identity were. The Bakonzo and Baamba people felt culturally and politically excluded from Tooro’s centralized monarchy and demanded autonomy. Their struggle became a land-centered cry for recognition, and it evolved into a secessionist conflict^9. This painful history shows that even within Tooro, land and language must be handled with justice and listening, not just cultural pride.

3.Language + Land = Legacy

Today, the preservation of Rutooro and the protection of ancestral lands has become a renewed struggle in the age of globalization. As urbanization spreads and digital languages dominate, many young Batooro are losing fluency in their own tongue. A 2020 linguistic survey by Makerere University found that only 48% of school-going children in Tooro sub-region could fluently speak Rutooro without mixing English^10. Similarly, land conflicts have increased, with customary land being grabbed by elites and multinational investors. Oil explorations in the Albertine Graben region have also raised fears of ecological and spiritual disruption.

In response, cultural institutions are reviving Empaako ceremonies, digitizing Rutooro stories, and protecting sacred forests in collaboration with environmental activists. The Omukama himself has become a cultural diplomat, urging the youth to “learn English to survive, but speak Rutooro to remember who you are.”

As Prof. Kwasi Wiredu once wrote, “In African philosophy, language is not only speech—it is rootedness.” When language dies, the tree falls. When land is lost, the altar crumbles.

Tooro stands as both a warning and a witness. The Kingdom reminds Africa that development must never come at the cost of spiritual identity. That tongues once silenced must be revived with poetry and pedagogy. That land once stolen must be reclaimed, not just for food, but for memory.

“Enteko y’obwengye eri aha mwoyo” — “The throne of wisdom is in the spirit.”. And in Tooro, that spirit speaks in Rutooro, and walks upon the hills of home.

PART IV: THE FEMININE CROWN — Women, Royal Power, and the Sacred Legacy of Tooro

“When a woman walks into the forest, she leaves a path behind her. But when she walks into history, she becomes the forest itself.” — Lunyoro proverb. In the great kingdoms of Africa, women were not shadows of the throne but the very soil on which it stood. In Tooro, the feminine has always worn many crowns—of power, of counsel, of endurance. To speak of Tooro without invoking the women of the palace, the shrine, and the field is to speak of the moon without its light.

From its very founding in 1830, Tooro was not a kingdom of men alone. Though Prince Kaboyo Olimi I led the political secession from Bunyoro-Kitara, the process was not void of female influence. Oral tradition preserved by the Batooro clan elders asserts that Kaboyo’s mother, a woman of royal Bunyoro blood, was instrumental in urging him to pursue independent authority, warning him that “the river that overflows must find its own bed.” Her voice, like many women’s in precolonial Africa, came not through direct rulership but through matriarchal diplomacy—whispers behind the veil that altered the winds of power.

The queens of Tooro—Omugo (Queen Mother) and Batebe (Princess Royal)—occupied sacred and political roles that rivalled and sometimes surpassed those of their male counterparts. The Batebe, in particular, stood as the King’s chief advisor, often referred to as “the King’s twin in spirit,” a position shared with similar female offices across the continent, such as the Asantehemaa of the Ashanti Empire or the Rain Queens of the Balobedu in southern Africa. Tooro’s Batebe advised on matters of war, land, and succession. As late as the 1940s, colonial administrators like H.B. Thomas documented how Princess Agnes Kaboyo, then Batebe, was “held in such esteem that her word carried the weight of two councils.”

But the feminine force in Tooro transcended the palace walls. It bled into the soil. The empango (coronation) of every Omukama is not complete without women performing the Ekitaaguriro—the royal dance that invokes ancestors and blesses the throne. These rituals are not aesthetic. They are ontological. They affirm that power, to be legitimate, must pass through the womb of the people.

In the colonial era, the matriarchs of Tooro bore a triple burden: guardians of culture, shields of the family, and sometimes, rebels in their own right. During the Buganda-supported British suppression of the Tooro Kingdom in 1893, while King Daudi Kasagama Kyebambe IV was forced into submission and eventual coronation under British suzerainty in 1896, his sister—Princess Leya—is remembered in local folklore as a woman who “hid the drums and calabashes” to protect sacred regalia from colonial desecration.

Women were also essential to the cultural preservation movement during the kingdom’s abolition from 1967 to 1993. When kingdoms were banned under the regime of Milton Obote, it was Tooro women’s unions and church mothers’ guilds that preserved Runyoro-Rutooro lullabies, riddles, and the oral genealogies of Tooro’s sacred lineages. According to Dr. Sylvia Nannyonga-Tamusuza, these women “created cultural wombs in exile, refusing to let the kingdom die even when the law pronounced it dead.”

And then came Omugo Best Kemigisa Akiiki, widow of Omukama Patrick Olimi Kaboyo II and mother of King Oyo Nyimba Kabamba Iguru Rukidi IV, Uganda’s youngest king, enthroned at the age of three years in 1995. Omugo Best stepped into a sacred chaos—her child had inherited a kingdom still bruised from abolition, with cultural institutions in ruin. Yet, she became not only a regent, but a builder of bridges. She founded the King Oyo Foundation, championed girl-child education, and represented Tooro across global forums, asserting that the feminine throne could be both traditional and transformative.

However, her reign has not been without contest. Accusations of mismanagement and internal palace conflict have emerged, notably during the 2009 royal controversy over land and regalia⁵. These moments remind us that royal womanhood, too, is subject to the fractures of modernity. But to judge the crown solely by its cracks is to ignore the gold that holds it together.

The Tooro Women’s Council, reestablished after restoration in the 1990s, has since initiated cross-generational empowerment programs, reviving dying crafts like omweso (stone board games) and herbal medicine. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) 2021 report on cultural institutions, over 68% of cultural revival projects in Tooro are women-led.

Even now, women like Princess Ruth Komuntale, the American-educated sister of King Oyo, navigate the tension between tradition and diaspora. Her very visibility on global platforms—while critiqued by some—is a symbol of Tooro’s evolving femininity: part ancient, part modern, but wholly African.

So let no one say Tooro’s crown belongs to the king alone. It was carved by many hands, but it was polished by the fingers of women who knew that memory must be worn like jewelry, not stored like grain. “A woman who knows the names of the dead,” the Batooro say, “can summon the living.”

PART V: Thrones in the 21st Century — Tooro’s Modern Relevance in Uganda and Beyond

“The baobab does not lose its roots when the wind shifts. It bends, but it remembers.” In the mosaic of post-independence Uganda, where kingdoms were once dissolved and then reborn, Tooro stands today not as a mere emblem of nostalgic royalism but as a catalyst of soft power, cultural diplomacy, and development innovation. The modern relevance of the Tooro Kingdom is best understood through its ability to redefine monarchy, not as a political rival to the state, but as a cultural pillar, developmental partner, and spiritual guide in a nation still stitching together the scars of colonialism, dictatorship, and neoliberal displacement.

Tooro’s symbolic resurgence began with the restoration of traditional institutions in 1993, as part of President Museveni’s reconciliation gesture with Buganda and other southern kingdoms. However, unlike Buganda which often positioned itself as a political pressure bloc, Tooro adopted a subtler approach. It recast its monarchy not in the language of opposition, but in the quiet grammar of community service, cultural literacy, and youth mobilization. Under King Oyo Nyimba Kabamba Iguru Rukidi IV, who ascended the throne in 1995 at just three years old, Tooro entered the global consciousness as the home of the world’s youngest monarch^1. His coronation, televised across Africa, became a metaphor for generational transition. But the young Omukama was not merely ornamental—he grew into the role, shaping the Kingdom’s voice in spheres as varied as climate advocacy, cultural diplomacy, education, and health.

In 2009, King Oyo launched the King Oyo Foundation, a non-profit platform with the mission to empower youth, promote environmental conservation, and support health and education access in the Tooro sub-region^2. Through the foundation, royal authority has been redirected into community empowerment. In 2011, for example, the foundation began reforesting efforts across Fort Portal and the slopes of the Rwenzori Mountains, partnering with Uganda’s National Forestry Authority to combat deforestation, a crisis worsened by logging, charcoal burning, and displacement from oil exploration in Bunyoro and beyond^3. The symbolic planting of indigenous trees is not just an ecological gesture—it is a sacred act of reclamation. As the Baganda say, “Omuti ogusinga ogw’eddagala guli mu kibira”—the most healing tree is found deepest in the forest.

Diplomatically, Tooro has embraced cultural Pan-Africanism, drawing from the wisdom of historical African alliances. In 2013, King Oyo met with King Zwelithini of the Zulu Nation in South Africa, discussing traditional leadership and indigenous justice systems. In 2019, he joined other monarchs in Accra, Ghana at a Pan-African royal conference seeking to reposition traditional leaders in Africa’s development agenda. In these gestures, Tooro reveals a rebirth of African monarchy not as relic, but as moral compass, echoing Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Gyekye’s argument that tradition must be “re-rooted, not uprooted” if Africa is to heal.

Locally, Tooro Kingdom continues to shape policy, not through coercion, but consultation. Its influence in district-level education planning, such as cultural inclusion in school curricula in Kabarole and Bunyangabu, has been documented in the Uganda Ministry of Education reports (2019). In 2022, the Kingdom launched a scholarship program for girls in science and technology fields, under the guidance of Queen Mother Best Kemigisa, reflecting not just gender inclusion but gender leadership, a motif explored earlier in Part IV.

Perhaps most prophetically, the Kingdom of Tooro has positioned itself as an inter-religious and interethnic bridge in a region marked by occasional tensions between Bakiga, Batooro, and Banyarwanda populations. During the 2016 post-election tribal clashes in western Uganda, the Kingdom organized cultural dialogues that brought together religious leaders, elders, and civil society, showing that royalty in Africa, when unshackled from colonial definitions, can still function as peace-maker and reconciler^5.

Even Uganda’s central government, often skeptical of traditional authority, has acknowledged Tooro’s constructive role. In 2017, President Museveni, during a speech in Fort Portal, praised the Kingdom’s efforts in environmental conservation and youth employment, noting that “what Tooro is doing can be a model for cultural institutions across Africa.”^6 While such praise may be politically calculated, it reflects a wider recognition: Tooro is not passive nostalgia—it is strategic heritage.

As African scholars like Prof. Olufemi Taiwo argue, “the future of Africa lies not in the denial of tradition, but in its intelligent deployment.”^7 Tooro is such a deployment: not frozen in 1830 when it broke away from Bunyoro, not trapped in 1967 when it was abolished, not merely romanticized in 1993 when it was restored—but dynamic, dialogical, and deeply involved in today’s African questions: What is development? Who speaks for the youth? What is the role of the sacred in statehood?

Tooro is no longer just the Kingdom of misty hills and royal drums. It is the Kingdom of forest regeneration, of feminist scholarships, of Pan-African diplomacy, of digital youth movements, and ancestral vision. It is an answer whispered into the whirlwind of modern Africa’s identity crisis. “Obwengye bw’omukulembeze bwebusobola okukunganya eggwanga” — The wisdom of a leader is known by their power to unify a nation. Tooro is becoming such wisdom.

PART VI: Of Thrones and Tablets — The Contemporary Relevance of Tooro in Uganda and Beyond

“A king without a people is but a shadow in the sun.” — Somali proverb—”The future of African kingdoms lies not in nostalgia, but in negotiating memory with modernity.” — Achille Mbembe. In a world spiraling toward digitization, global governance, and economic metrics, what use is a kingdom? Tooro answers with a quiet confidence rooted in reinvention. Far from the colonial caricatures of primitive feudalism, Tooro today presents itself as a non-political but culturally vibrant institution that contributes to Uganda’s soft power, civic engagement, and communal cohesion. The reinstatement of kingdoms in Uganda under Article 246 of the 1995 Constitution granted traditional institutions legal recognition as cultural bodies—devoid of direct political power, yet rich in advisory, ceremonial, and social influence. It is through this constitutional window that Tooro has reemerged, not simply as heritage, but as a living civic organism.

King Oyo Nyimba Kabamba Iguru Rukidi IV, enthroned in 1995 at the age of three, has evolved from symbolic child king to global youth advocate. By his mid-twenties, he had already partnered with international agencies like UNFPA, championing causes like youth education, climate resilience, and gender equality. His 2010 address at the World Youth Conference in Mexico framed Tooro as a laboratory for harmonizing ancestral identity with contemporary governance models. It was not a political speech, but a cultural declaration: Tooro is not retreating into myth—it is stepping forward as a model for heritage-infused dedevelopment.

1.Education as Cultural Continuity: The Empaako Curriculum

One of the most poignant examples of Tooro’s relevance lies in its embrace of education as both a cultural and civic tool. In 2013, the UNESCO recognition of the Empaako naming tradition as an intangible heritage in need of safeguarding catalyzed a regional educational movement. The Kingdom of Tooro, in partnership with cultural NGOs and the Uganda National Commission for UNESCO, began integrating indigenous knowledge systems into local curricula—reviving Rutooro language instruction, oral traditions, and ritual literacy in community schools.

Statistically, over 78% of children in Tooro’s rural sub-counties now receive primary school instruction with culturally tailored modules in language and environment studies, according to a 2023 report by Uganda’s Ministry of Education and Sports. The traditional greeting of “Empaako”, once mocked as backward, is now being digitalized into children’s learning apps, cultural storytelling festivals, and diaspora language schools. Culture has become not a burden but a bridge.

2.Sacred Forests and Ancestral Rivers: Tooro’s Eco-Spiritual Diplomacy

Where many governments treat climate change as a statistical crisis, Tooro treats it as a spiritual rupture. In 2021, the Kingdom declared several of its sacred groves and royal tomb lands as community conservation zones, in partnership with the Uganda Wildlife Authority and Nature Uganda. The kingdom has been pivotal in defending River Mpanga and the Rwenzori mountain ecosystem, both of which face hydroelectric and extractive threats. According to the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), over 35% of forest cover in Western Uganda has been lost between 1990 and 2020—and Tooro has become one of the few cultural entities actively resisting this ecological erosion.

Traditional Tooro cosmology, which teaches that rivers are mothers and forests are shrines, has found synergy with global climate science. His Majesty King Oyo’s 2022 Climate Justice Tour in Europe, including visits to the COP27 preparatory forum, helped position Tooro as an African voice for indigenous-centered climate action. The king’s address at the Swedish Royal Palace in 2022, where he stated, “When we cut a sacred tree, we do not just lose oxygen—we lose memory,” reverberated across ecological networks. Indeed, Tooro is showing that climate action can be a form of ancestral repair.

3.Youth, Digital Memory, and Diasporic Bridges

The median age of Uganda’s population is 16.3 years, with youth unemployment standing at over 13% nationally and 20% in urban centers. In this context, the Kingdom of Tooro’s youth initiatives offer cultural mentorship as economic and psychological empowerment. Through platforms like “Ekyooto Ha Mpango”, a digital cultural festival launched in 2020, the Kingdom now connects youth in Fort Portal, Kampala, and the diaspora in real-time forums of heritage, innovation, and Pan-African debate.

A 2024 report by the Uganda Communications Commission shows that over 62% of Western Ugandan youth between the ages of 18–30 follow cultural pages or accounts online, indicating a hunger for identity in the digital age. Tooro is tapping into this longing not through archaic rituals alone, but by curating podcasts, YouTube series, and mobile apps that teach Rutooro proverbs, royal history, and environmental ethics. In this way, Tooro becomes a “digital palimpsest,” rewriting itself on new screens while preserving its ancestral ink.

4.The Kingdom and the State: Beyond Antagonism

Critics argue that monarchies are relics unsuited for republican states. But Tooro demonstrates that kingship need not oppose democracy—it can supplement it with moral authority, community mediation, and cultural diplomacy. The King of Tooro routinely convenes with President Yoweri Museveni, not in competition, but in consultation. The Tooro Development Forum, launched in 2016, serves as a think-tank aligning kingdom priorities with Uganda Vision 2040. It also liaises with Bunyoro-Kitara, Buganda, and Busoga, signaling a rising inter-kingdom Pan-African solidarity model rooted not in politics, but in collective cultural governance. Anthropologist Dr. Okello Lucima argues that Uganda’s kingdoms are “sites of sub-sovereignty,” where the state and the spirit co-govern parallel narratives of nationhood^1. Far from being a threat, Tooro’s survival is proof that multiple sovereignties can coexist—and even enrich one another.

PART VII: THE PROPHETIC LEGACY — TOORO’S MESSAGE FOR AFRICA’S FUTURE

“The future is not a place we are going to, but one we are making; and Tooro holds the sacred compass.”

— Adapted from African futurist thought. In the annals of Africa’s kingdoms, Tooro holds a special place not simply because it survived colonial dismemberment and postcolonial upheaval, but because it embodies a vision—a prophetic legacy—that speaks to the deepest wounds and highest hopes of the continent. Tooro’s story is a mirror and a lamp: a mirror reflecting Africa’s fractured past and a lamp illuminating a path towards radical restoration and reclamation.

1.Decolonizing Time, Space, and Knowledge

Tooro’s prophetic message begins with time itself. While Western modernity insists on linear progress, African cosmologies—including that of Tooro—embrace a cyclical, layered temporality, where past, present, and future exist simultaneously. This is not mere philosophy but a strategic epistemology that challenges colonial rupture.

In 2019, Achille Mbembe, the Cameroonian philosopher, described Africa’s future as a “project of unlearning” the colonial archive and recovering “the fullness of memory beyond trauma”^1. Tooro’s continued cultural revival—its ceremonies, language, and spiritual practice—acts as a living archive resisting epistemic erasure. It is this archive that African scholars call “historical sovereignty”^2: the power to tell one’s own story, define identity on one’s own terms, and reclaim knowledge that colonialism sought to bury.

In practice, Tooro’s preservation of Runyoro-Rutooro language and oral traditions serves not only cultural pride but political decolonization. The 2023 UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger lists Runyoro-Rutooro as “vulnerable” but rising thanks to grassroots revival efforts led by Tooro’s cultural institutions^3. These efforts align with the Pan-African movement to decolonize African education systems, resisting the dominance of colonial languages and epistemologies—a struggle deeply articulated in Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s seminal work, Decolonising the Mind (1986).

2.The Kingdom as a Sanctuary of Resistance

Across Africa, kingdoms have been ambivalent players in the colonial and postcolonial state-building drama. Tooro’s prophetic role is rooted in its resilient survival as a cultural sanctuary—a place where African values of ubuntu (shared humanity), ancestral respect, and communal responsibility remain vibrant despite political marginalization.

Between 1967 and 1993, when kingdoms were officially banned by Uganda’s central government, Tooro’s royal family and people endured systematic erasure. But through clandestine gatherings, oral storytelling, and clandestine religious observances, the kingdom preserved not only memory but hope. According to historian Andrew N. Witte, the underground cultural resistance in Tooro during this era laid the groundwork for the kingdom’s revival as a moral and cultural force in Uganda’s post-Amin era.

This prophetic stance echoes broader African struggles against neo-colonialism and cultural imperialism. Tooro’s renewed role as a cultural conscience was evident during the 2017 “Decolonize Africa” Conference in Nairobi, where cultural leaders from Tooro articulated a vision of cultural sovereignty as a precondition for political and economic freedom^6.

3.Pan-African Solidarity and Kingdom Diplomacy

Tooro’s message to Africa is also one of unity in diversity. In a continent fractured by colonial borders and ethnic conflicts, Tooro’s sustained collaboration with other monarchies—from Buganda and Bunyoro in Uganda, to the Ashanti in Ghana, to the Zulu in South Africa—represents a grassroots Pan-Africanism anchored in culture and tradition.

The 2019 Pan-African Royal Summit in Accra saw King Oyo and his contemporaries issue the Accra Declaration, emphasizing that “traditional institutions must be revitalized to heal the fractures of colonialism and guide African development rooted in our own values”^7. This summit was historic in recognizing kingdoms as custodians of peace, culture, and ethical governance outside the state apparatus.

These regional royal networks intersect with African Union initiatives. The African Union’s 2019 Agenda 2063, a strategic framework for socio-economic transformation, explicitly acknowledges the role of traditional institutions in peacebuilding, cultural heritage protection, and youth empowerment—all pillars of Tooro’s mission today.

4.Statistics of Hope and Challenge

Yet, the prophetic legacy is not untroubled. Uganda’s youth face daunting statistics: over 37% live below the national poverty line, youth unemployment hovers at 13.5% nationally, and rural-to-urban migration strains infrastructure and cultural continuity^9. In this context, Tooro’s efforts to integrate youth education, cultural revival, and environmental stewardship become acts of resistance against despair.

Further, with climate change disproportionately impacting Africa—sub-Saharan Africa’s temperature rising 1.5 times faster than the global average according to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (2022)—Tooro’s ecological activism and ancestral conservation practices gain global urgency^10.

5. Spiritual Renewal as Political Revolution

Tooro’s prophetic message culminates in the fusion of spirituality and politics. Unlike the secular postcolonial state, the Kingdom holds to a worldview where the sacred and the political are inseparable. The Empango festival, celebrated annually, is not a mere pageant but a reaffirmation of the covenant between the living, the ancestors, and the land.

This worldview echoes African feminist theologian Mercy Amba Oduyoye’s vision of African spirituality as a source of radical liberation and ecological balance^11. In this, Tooro challenges modernity’s extraction-driven capitalism with an ethics of care, reciprocity, and ancestral accountability. The Kingdom’s cultural festivals, rituals, and educational programs serve as crucibles for renewing African identity rooted in land, language, and lineage—elements central to Africa’s healing and resurgence.

PART VII — THE SACRED MASK AND THE VANISHING MEMORY: Challenges of Modernity, Corruption, and Cultural Erosion in Tooro

“If a drum forgets its rhythm, the dance will stumble into dust.” — Bakiga Proverb. There are seasons when a kingdom does not fall by conquest but by forgetting. Such is the fragile paradox of Tooro in the twenty-first century—resplendent in royal garments but shadowed by the eroding tides of memory, modernity, and institutional compromise. Beneath the regal celebrations and parades lies a contested space where culture battles consumerism, tradition is sold as tourism, and the sacred is sometimes shelved for political comfort.

The core of Tooro’s contemporary tension lies in the ongoing battle between cultural preservation and commercial commodification. Institutions like the Tooro Kingdom Administration, once stewards of the land, language, and spiritual heritage, are now burdened with both economic survival and relevance. As global capitalism and urban migration reshape African identities, Tooro’s youth increasingly speak in the accents of the West, dress in foreign names, and regard their royal heritage as folklore—interesting, perhaps, but not necessary. According to a 2022 report by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, over 62% of Tooro’s youth between 18–35 have never participated in a traditional cultural rite, and more than 70% do not speak Rutooro fluently. The language that once preserved the soul now risks extinction within two generations.

And yet, this crisis is not merely linguistic or symbolic—it is infrastructural and political. The kingdom, despite its restoration in 1993 under Article 246 of the Ugandan Constitution, remains financially crippled. In 2021, the Office of the Auditor General found that Tooro Kingdom’s financial disclosures lacked transparency, with unaccounted-for government funds and growing dependence on donor organizations like Cross-Cultural Foundation of Uganda (CCFU) for cultural projects. The 2020 exposé by The Observer Uganda alleged internal mismanagement in the leasing of kingdom land to private investors without community consultation—especially land around Fort Portal City, now a tourism hotspot. This echoes wider trends across Uganda where cultural institutions, lacking state support or checks, succumb to clientelism and elite capture.

Meanwhile, the custodians of moral memory—the royal family and its advisers—often walk a tightrope. King Oyo Nyimba Kabamba Iguru Rukidi IV, though internationally celebrated (notably by UNDP and the World Economic Forum) as a young leader, faces criticism at home for being more visible abroad than within the villages where Tooro’s soul still weeps. His 2014 initiative Ekyooto Ha Mpango (The Fire Place), meant to revitalize Tooro’s oral storytelling and intergenerational dialogue, has seen declining participation since 2019, with fewer than 400 active elders registered across Tooro, compared to over 3,000 in 2002.

The kingdom also struggles with the ethical cost of aligning with state politics. While some argue that cordial relations with the Museveni government have brought stability, others whisper of compromises—instances where the palace fell silent when land rights were violated, or when corruption scandals rocked local councils. The 2018 Kasese evictions, which displaced over 600 families in areas bordering Tooro, received no official protest from the kingdom, despite cultural and ancestral ties to the affected communities.

All these realities raise urgent theological and philosophical questions. Can a kingdom survive without moral authority? Can royalty exist without prophetic witness? As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o warned in Decolonising the Mind, “The biggest weapon wielded… is the domination of the mental universe.” When cultural institutions lose their prophetic teeth, they become ornaments—beautiful, empty, and forgotten.

And yet, it is not too late. All around Tooro, sparks remain. Grassroots efforts like the Rutooro Language Revival Collective (RLRC) and initiatives by youth groups to digitize oral histories show that not all is lost. In 2023, a pilot project led by Makerere University and Mountains of the Moon University documented over 1,200 folktales and indigenous healing practices still alive in the hills of Kyenjojo and Kamwenge districts. These fragments, if woven with vision, can become a new tapestry.

But Tooro must decide. Will it remain a living drum, pulsing with memory, or will it become a silenced relic, paraded for tourist photographs? Will it resist being swallowed by the great forgetting?. “Akacence kabileho kabugumireho.” – A small fire that remains must be protected lest the night devours us.

PART VIII — TOORO IN THE PAN-AFRICAN TAPESTRY: Sovereignty, Memory, and the Sacred Futures of African Kingdoms

“A cow is never just one cow—it is the song of its ancestors, the salt of its soil, the cry of its herd.” — Basongora Proverb (Western Uganda).To speak of Tooro is to whisper into the ancestral bones of the continent itself. It is to remind ourselves that African kingdoms, though scattered by the winds of colonial conquest, neocolonial policy, and internal corrosion, still pulse with sacred significance. Tooro is not merely a kingdom in Uganda—it is one of Africa’s surviving mirrors, reflecting both the beauty and the bleeding of traditional sovereignty in the postcolonial era. In Tooro’s unraveling and resurrection, Africa must see both a warning and a possibility.

Tooro’s story parallels that of many African monarchies—spiritual institutions caught between the thrones of cultural preservation and the towers of political survival. In Nigeria, the Benin Kingdom, once feared and majestic, today sells its stolen bronzes back from European museums while its Oba struggles to protect ancestral lands from commercial encroachment. In Ghana, the Ashanti Kingdom, though fiercely proud, must tread lightly under state politics while using royal pageantry to attract investment and tourism. In South Africa, the Zulu Kingdom has been riddled with internal succession crises and legal battles over land rights, especially following King Goodwill Zwelithini’s death in 2021. And in Buganda, just next door to Tooro, cultural revival is often compromised by elite bargaining with the Ugandan government.

Each kingdom tells the same tragic song in a different key. The chorus is familiar: Restored but not empowered. Revered but not resourced. Visible but voiceless. In 2022, a policy paper by the African Union’s Department of Culture and Heritage revealed that less than 15% of traditional monarchies in Africa receive adequate funding or constitutional protection from their national governments, despite their contributions to peacebuilding, environmental conservation, and social cohesion.

But Tooro’s tale is unique in its youth. King Oyo, crowned at only three years old in 1995, symbolizes both the fragility and future of African kingdoms. His reign—spanning the tail end of Uganda’s guerrilla recovery and the dawn of Africa’s digital awakening—presents a sacred opportunity: to build a new kind of monarchy. One that is not beholden to colonial nostalgia or postcolonial power games but is instead rooted in service, prophetic leadership, cultural intelligence, and intergenerational memory.

Africa today teeters between the graveyard of its stolen artifacts and the laboratory of its cultural rebirth. Pan-African thinkers like Amílcar Cabral warned of the death of African societies not by guns alone but “by forgetting who they were and accepting the language of the enemy.” In this light, Tooro must not only restore its palaces but reclaim its pan-African consciousness—the idea that no kingdom is sovereign in isolation. Tooro must link arms with Bunyoro, with Benin, with Ashanti, with ancient Mapungubwe, and with the wounded statues of Axum and Nubia.

And the Church, the mosque, the shrine—they must all rise to protect what remains. For these institutions too are at risk of becoming echoes unless they see that the struggle to protect culture is not against modernity but against amnesia—the forgetting of the sacred.

In July 2025, at the UNESCO-African Monarchies Dialogue in Accra, scholars and elders proposed a “Covenant of Memory”—a charter where African kingdoms commit to sharing archival resources, protecting sacred sites, and teaching shared histories across borders. Tooro’s royal household was invited but did not attend. This absence, symbolic or accidental, reminds us that unless we gather at the ancestral fire, the night will come without storytelling—and without storytelling, we are only dust. “Omuntu abulwa empisa, afuuka nk’ekikere ekitalina nju.”— A person without roots is like a frog without a pond. (Tooro proverb )

CONCLUSION — WHEN THE DRUM IS SILENT, THE GRAVE DANCES: Tooro and the Sacred Burden of Restoration

“A nation that cuts off its roots does not fall—it vanishes.”

— Ancient proverb from the Luba Kingdom, DRC. Tooro is not merely a kingdom—it is a testimony, a trial, and a trumpet. In the long corridors of Africa’s postcolonial struggle, Tooro stands as a sacred riddle: How do you rebuild a throne when the soil has been salted by history? How do you dance again when the rhythm was outlawed and the dancers scattered?

From the fall of Tooro in 1967 by the decree of President Milton Obote, to its fragile restoration under President Museveni in 1993, the kingdom has walked a tightrope between heritage and survival. Though legally reinstated, Tooro’s monarchy remains constitutionally toothless, culturally burdened, and economically starved. The once-celebrated shrines, palaces, and institutions of the kingdom still bear the scorch marks of cultural exile. And yet, in the face of this erosion, the royal household has dared to live.

This is not a naive celebration. The journey of King Oyo is steeped in contradiction. His 1995 coronation at age three was a media miracle and a historical spectacle, but also an invitation to power without preparation. His reign has navigated family disputes, royal court infighting, constitutional marginalization, political co-optation, and cultural alienation. And yet, he has also pursued education, global diplomacy, and philanthropic projects such as the King Oyo Foundation and the Tooro Kingdom’s 25-Year Development Plan (2020–2045). Still, even these initiatives suffer from underfunding and lack of grassroots integration.

Meanwhile, the people of Tooro—especially its youth and women—wait for a renaissance not in words but in water, in schools, in sacred festivals restored, and in justice for lands lost. The Bataka clans, once custodians of ancestral authority, now find themselves litigating for land in Uganda’s overburdened courts. According to a 2023 report by the Uganda Land Commission, over 68% of contested land in Kabarole District overlaps with historically royal territory. And yet, traditional institutions are excluded from national land dialogue frameworks.

Across the continent, the fire flickers similarly. From the tombs of Buganda to the stones of Great Zimbabwe, African kingdoms remain suspended in a strange twilight—revered yet irrelevant, remembered yet silenced. The neo-colonial state, forged in the image of European governance, continues to view traditional kingdoms as symbolic relics rather than civic actors. Yet the hunger for cultural rebirth simmers beneath the surface. African youth, armed with smartphones and ancestral dreams, are beginning to ask the right questions. “Who are we without our shrines? What is progress if we forget the proverbs?”

The theological voice must not be absent in this moment. Scripture, too, tells of kingdoms that fell when justice was silenced and elders ignored. In Isaiah 3:5, we read, “The people will be oppressed, everyone by another and everyone by his neighbor; the youth will be insolent to the elder, and the base to the honorable.” Is this not Africa’s wound today?

Yet the same Bible also speaks of restoration. In Jeremiah 6:16, it says, “Stand at the crossroads and look; ask for the ancient paths, ask where the good way is, and walk in it, and you will find rest for your souls.” Tooro—and Africa’s other thrones—must now rise not to return to the past, but to remember the sacred logic that once governed it: that leadership was not domination, but stewardship; not power, but presence.

Let this work be a firewood offering for that rebirth. Let every cracked palace be swept, every bataka consulted, every Tooro child taught not only the English alphabet but also the drum language of their elders. Let the Empaako system, that ancient naming rite, not be reduced to folklore, but become a living liturgy of identity, sung in classrooms, churches, and courts alike. “Omukama takufiira mpango: The king does not die in a whisper.” (Tooro Proverb). Africa’s kingdoms may be politically stripped, but they are not spiritually dead. The bones still speak. The palaces still breathe. And Tooro, crowned in childhood, burdened by history, may yet teach us all that when the drum is restored, the dead dance again—and the living remember who they are.

References:

1. African Union Commission. (2019). Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. Addis Ababa.

2. Achille Mbembe. (2019). Critique of Black Reason. Duke University Press.

3. Amílcar Cabral. (1973). Return to the Source: Selected Speeches.

4. African Union Department of Culture and Heritage. (2022). Policy Paper on African Monarchies.

5. IPCC. (2022). Sixth Assessment Report – Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Geneva.

6. King Oyo Foundation. (2020). Tooro Kingdom 25-Year Development Plan (2020–2045). Fort Portal.

7. Lucima, Okello. (2018). Rethinking Kingship in Postcolonial Uganda. Makerere University Press.

8. Ministry of Education and Sports, Uganda. (2023). Indigenous Languages and Curriculum Integration Report. Kampala.

9. Makerere University & Mountains of the Moon University. (2023). Documentation of Tooro Folktales and Healing Practices. Fort Portal.

10. Mbiti, John S. (1990). African Religions and Philosophy. Heinemann.

11. Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development Uganda. (2022). Gender and Child Protection Report. Kampala.

12. National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), Uganda. (2020). Forest Cover and Conservation Report. Kampala.

13. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. (1986). Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. James Currey Publishers.

14. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. (1993). Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms. James Currey Publishers.

15. Oduyoye, Mercy Amba. (1995). Daughters of Anowa: African Women and Patriarchy. Orbis Books.

16. Pan-African Royal Summit. (2019). Accra Declaration on Traditional Institutions. Ghana.

17. Rutooro Language Revival Collective (RLRC). (2023). Annual Report on Language Preservation. Fort Portal.

18. The Observer Uganda. (2020). Exposé on Tooro Kingdom Land Leases. Kampala.

19. Tooro Kingdom Administration. (2022). Annual Report on Cultural and Environmental Interventions. Fort Portal.

20. Uganda Bureau of Statistics. (2024). National Youth Indicators Report. Kampala.

21. Uganda Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Population and Language Usage Statistics. Kampala.

22. Uganda Land Commission. (2023). Report on Land Conflicts in Kabarole District. Kampala.

23. Uganda Communications Commission. (2024). Youth and Digital Heritage Usage Survey. Kampala.

24. UNESCO. (2013). Empaako Naming System of Western Uganda. Intangible Heritage Lists. Paris.

25. UNESCO. (2023). Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Paris.

26. UNFPA. (2021). Youth Education and Climate Resilience Reports. Kampala.

27. Witte, Andrew N. (2015). Cultural Resistance in Tooro, Uganda (1967–1993). Journal of East African Studies, 9(3), 450–472.