By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija, Independent Researcher

Emkaijawrites@gmail.com

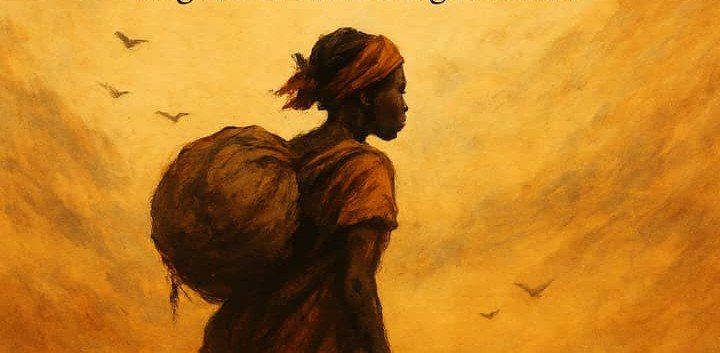

PART I — When the Sky Weeps: Opening Reflections on the Migrant Soul

“When the sky begins to weep, even the mountain packs a bag.” — Somali proverb

Migration is not a new wound on Africa’s soil — it is an ancient river, flowing with both memory and mourning. Before passports were inked and borders invented, people moved with the seasons, following rain, cattle, and rhythm. But now, across this continent of cracked lands and cracked hearts, movement often comes not from choice but from terror. The wind is no longer gentle. It carries with it the smell of gunpowder, the echo of boots, and the silence of burnt villages. The displaced are not merely statistics; they are living psalms of lamentation — Hagar reborn, Moses retold, Jesus re-exiled. They leave behind not only home but the name of home. And yet, the soil remembers. The sky remembers. The God who once said, “I have surely seen the affliction of My people” (Exodus 3:7) — still sees. This is not merely a humanitarian crisis. It is a theological earthquake. It shakes our understanding of borders, hospitality, and who belongs.

PART II — Definitions, Histories, and Scattered Seeds

“A person who does not know where the rain began to beat them cannot say where they dried their body.” — Igbo proverb

What does it mean to migrate — and what makes one a refugee? These are not just policy terms. They are the names of sorrow, the shapes of survival. A migrant may leave in search of better rain, but a refugee runs from fire. An asylum seeker carries fear in their blood and law in their hands. An internally displaced person (IDP) has been exiled within the borders of their own birth. These labels try to define pain, but the soul of the scattered cannot be easily shelved in UN language. In Africa, migration is as old as our myths. The Bantu migrations swept across millennia, shaping nations with language and kinship. Later came migrations birthed by chains — the Atlantic slave trade, the Arab slavers, and colonial resettlement. After the white man’s map was carved across the continent, new borders fractured old homelands. Somalia was split, Sudan divided, Congo butchered, and Rwanda made to burn. Each movement bore wounds that still walk with us today.

And in the present hour, we see a new flood: the exodus from Tigray, the bleeding of Darfur, the drowning in the Mediterranean, the forgotten camps in Cameroon. According to the UNHCR, as of 2024, over 44.3 million people in Africa are forcibly displaced — a continent carrying nearly one-third of the world’s total refugees and IDPs.¹ Behind every number is a name, a face, a grandmother with a torn Bible in her cloth bag. This is not just history; it is prophecy walking in bloodied sandals. If we do not understand the past migrations, we will misread the present ones — and fail to prepare for the ones still coming, as climate dries the rivers and war multiplies like locusts.

PART III — The God Who Migrates: Theology from the Borderlands

“God does not live in palaces, but walks with the homeless.” — African spiritual saying

The sacred story of migration is etched deeply into the scrolls of scripture, where God reveals Himself not as a distant monarch but as a pilgrim and protector of the displaced. From the trembling desert where God called Moses to lead a wandering people (Exodus 3:7–10), to Abraham’s journey into an unknown land (Genesis 12:1), the biblical narrative breathes with movement and exile. Jesus Himself became a refugee when his family fled Herod’s murderous decree, taking refuge in Egypt (Matthew 2:13–15). These holy wanderings are not incidental; they reveal a divine solidarity with those uprooted and oppressed. The Psalmist sings of God as a refuge in times of trouble (Psalm 91), and the prophets call Israel to welcome the stranger with open arms (Leviticus 19:34). The God who calls us to justice is a God who dwells among the displaced, who commands us to “loose the chains of injustice and set the oppressed free” (Isaiah 58:6).

In African theology, this divine presence among the displaced resonates deeply. The concept of Ubuntu — “I am because we are” — teaches us that the stranger’s pain is our own, that community is not a fixed geography but a shared journey. The God of Exodus is still on the move in the cracked streets of Khartoum, the dusty camps of Dadaab, and the flooded villages of Mozambique. This theology calls the church and all faith communities to become sanctuaries, to embody hope in the wilderness, and to bear witness to the sacred dignity of every migrant. For to welcome the stranger is to welcome God Himself — a truth woven through both scripture and the ancestral heartbeats of Africa.

PART IV — The Burning Causes: War, Climate, and Oppression

“When the lion’s teeth are bared, even the trees tremble in silence.” — Yoruba proverb

Behind every migration is a story scorched by suffering — the harsh fires that drive a people from their homes. In Africa today, war is one of the fiercest lions stalking the land. From the endless cycle of violence in Sudan’s Darfur and the Tigray conflict in Ethiopia, to the shadow wars of the Congo’s eastern provinces and Boko Haram’s terror across Nigeria and the Lake Chad basin, armed conflict fractures families and shatters communities. These battles are often fueled by old wounds—ethnic divisions planted by colonial masters, struggles for land, power, and identity — and they bloom into exodus.

Yet war is only part of the story. The earth itself groans under the weight of climate change, a slow-burning furnace turning fertile lands into dust bowls. The Horn of Africa, once the cradle of pastoral life, faces relentless droughts; Mozambique’s rivers flood with despair; the Sahel becomes a battleground for survival. Hunger and thirst push countless mothers to carry children through hostile lands, hoping for a promise that feels farther than ever.

Political oppression, too, tightens its noose. Authoritarian regimes in Eritrea, Burundi, and elsewhere turn dissenters into exiles. The young are left to wander, jobless and hopeless, caught in the grip of economic despair. The grinding poverty that once seemed eternal now becomes a river of departure, flowing toward uncertain shores.

Together, these forces converge like a storm — displacing millions, uprooting histories, and testing the endurance of human hope. To understand migration without naming these fires is to see only the ashes and forget the flames that burned the homes in the first place.

PART V — The Faces Behind the Numbers: Testimonies and Truths

“The wound that bleeds in silence cries the loudest in the heart.” — Shona proverb

Behind the cold statistics that speak of millions displaced, behind the charts and reports, lie faces—eyes that have seen too much, stories carved deep into flesh and spirit. Amina is one such face, a woman from the dusty plains of Darfur who fled with her children after her village was razed to ash. She carries no passport, only memories and a ragged shawl where she hides a worn family Bible. “We left our home,” she says softly, “because death knocked loudly at our door.”

According to UNHCR, Africa hosts over 44 million forcibly displaced people as of 2024—refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced persons.¹ This staggering number holds multitudes of Aminas, each a living testament to survival against unimaginable odds. In the sprawling Bidi Bidi camp in Uganda—the second largest refugee camp in the world—children play beneath tin roofs while mothers stitch dreams from fabric scraps. In the camps of Kakuma and Dadaab, hope wrestles daily with despair, as aid struggles to keep pace with need.

These are not merely passive victims; many displaced Africans are agents of resilience, creativity, and resistance. They rebuild shattered communities, teach one another, and preserve the sacred threads of culture and faith amid exile. Yet, their stories remain muted in global discourse, drowned by the noise of politics and prejudice. To hear their voices fully is to be called into a sacred encounter—a meeting of the sacred and the suffering, the divine and the displaced.

In their testimonies lie the raw pulse of migration — not as an abstract phenomenon but as the living, breathing embodiment of loss and hope entwined.

PART VI — Borders and Barriers: The Global Face of Racism and Exclusion

“The river that refuses to flow only drowns the village.” — Akan proverb

Migration does not end at the edge of one continent; it clashes against the jagged walls of another’s fear and exclusion. African migrants fleeing war and famine often find themselves caught in a web of borders that are less lines on maps than gates of rejection and suspicion. In the Mediterranean Sea, thousands drown annually—souls swallowed by cold waves, their stories erased beneath the water. Yet, their deaths ripple silently through history’s memory.

The global response exposes a bitter truth: racism and double standards carve the refugee landscape. The swift and generous reception of Ukrainian refugees in Europe contrasts painfully with the slow, hostile treatment meted out to African asylum seekers.² News headlines and policies reveal a world that values some lives over others, that criminalizes African movement while celebrating European displacement as tragedy.

These barriers are not only physical but systemic—visa denials, detention centers, xenophobic rhetoric, and legal limbo. The African migrant is too often cast as a threat, an “other” to be contained or expelled, not a human being bearing God’s image. Yet, beneath these walls, the heartbeat of hospitality calls — a call to remember that we were once strangers in foreign lands, and that the God of Exodus commands us to love the alien and protect the stranger (Deuteronomy 10:19).

The refusal to welcome the displaced reveals a spiritual poverty as deep as any drought. The true exile is not only the one who flees but the one who refuses sanctuary.

PART VII — Forgotten Camps, Forgotten Lives: The Theology of Neglect

“A tree with no roots cannot stand against the storm.” — Swahili proverb

Within the vastness of the African continent lie countless refugee camps — places where time itself seems to pause in limbo, where lives are suspended between yesterday’s home and tomorrow’s unknown. Bidi Bidi in Uganda, Kakuma and Dadaab in Kenya, Nduta in Tanzania — these are not mere temporary shelters, but sprawling cities of exile that have stretched on for years, sometimes decades. Yet they remain largely invisible, neglected by the global gaze and burdened by insufficient resources.

The conditions are harsh: overcrowded tents, scarce clean water, inadequate medical care, limited schooling, and the ever-present threat of violence, exploitation, and despair. Here, childhoods are stolen, dreams deferred, and spirits tested. Theologically, this neglect is a wound against the very heart of God’s justice — a failure to embody the divine call to care for “the least of these” (Matthew 25:40). It is a scandal when God’s children live in liminal spaces, forgotten by nations and ignored by the powerful.

African governments, often overwhelmed and underfunded, struggle to provide adequate protection, yet many carry the lion’s share of the refugee burden with grace and generosity. The international community’s failure to adequately support these camps exposes a moral bankruptcy that calls for prophetic outrage and renewed commitment.

The church and faith communities are summoned to become sanctuaries, advocates, and sources of healing within these forgotten lands. For to forget the refugee is to forget our own humanity and the God who calls us to welcome the stranger as kin.

PART VIII — Prophetic Hospitality: The Church and Sanctuary

“A tent too small for a stranger invites the storm inside.” — Luo proverb

In the face of exile’s anguish and displacement’s desolation, the African church and all faith communities stand at a crossroads. Will they mirror the walls and borders that exclude, or will they open wide the gates of sanctuary, becoming places where the lost find refuge and the weary, rest? The biblical mandate is clear: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares” (Hebrews 13:2). This call resonates deeply with the African values of Ubuntu and Ujamaa—a communal embrace that sees the stranger not as outsider but as family.

Yet, this sacred duty is fraught with challenges. Churches and mosques face political pressures, resource constraints, and at times, internal prejudices that mirror society’s fears. Despite this, many faith communities have become lifelines—offering food, shelter, spiritual counsel, and advocacy. In Uganda, faith groups have partnered with humanitarian agencies to transform camps like Bidi Bidi into centers of learning, healing, and hope.

Prophetic hospitality is not merely charity; it is resistance against a world that dehumanizes the displaced. It is an enactment of God’s kingdom where walls crumble, and all are welcomed at the table. The church’s witness in this regard becomes a powerful critique of states and systems that turn their backs on the vulnerable. It is a call to embody the radical love of Christ, who Himself was once a refugee and stranger in a foreign land.

To offer sanctuary is to affirm that in the mosaic of humanity, every piece—no matter how fractured—reflects the divine image.

PART IX — Return, Redemption, and the Hope of Restoration

“Even the longest night gives way to the dawn.” — Wolof proverb

The story of migration, painful as it is, is not without the glimmers of hope that shimmer like stars in a desert sky. Scripture promises that exile will one day end — that return is woven into the tapestry of God’s redemptive plan. Jeremiah, speaking to the exiles in Babylon, declares, “For I know the plans I have for you… to give you a future and a hope” (Jeremiah 29:11). Isaiah paints a vision where scattered peoples are gathered from the four corners of the earth, “bringing the blind by a road they did not know” (Isaiah 42:16).

For millions of African refugees and migrants, the dream of home pulses strong in the heart—a dream that sustains through long years of displacement. Yet return is complex, fraught with challenges of lost land, lingering trauma, and fractured communities. Redemption is not simply a geographical act but a spiritual and social restoration, demanding justice, reconciliation, and rebuilding.

Many displaced Africans have become agents of transformation—carrying new knowledge, resilience, and faith to their homelands when the time comes. The African proverb reminds us: “It is the same water that washes the slave that will water the tree of freedom.” Migration can thus be a painful journey toward renewal, a crucible where the broken are made whole, and the scattered become a new kind of family.

The church, governments, and communities must prepare not just for exile but for homecoming — crafting policies and hearts open to welcome the redeemed, to rebuild nations, and to honor the sacred in every returnee.

PART X — A Call to Action: Justice, Mercy, and Sacred Hospitality

“A single bracelet does not jingle.” — Congolese proverb

The journey of migration is a clarion call to all who hear—the call to justice that breaks chains, the call to mercy that embraces the broken, and the call to hospitality that widens the circle of belonging. Governments, churches, communities, and individuals each hold a thread in this sacred tapestry of response.

The African Union, IGAD, ECOWAS, and other regional bodies must rise as protectors, crafting policies that shield the displaced from harm, ensure access to education and healthcare, and uphold human dignity. At the same time, international actors must reckon with their complicity—whether through arms trade, resource extraction, or climate neglect—that often fuels displacement.

Faith communities bear a holy responsibility to become sanctuaries in both word and deed—welcoming strangers, advocating for their rights, and challenging the systems that criminalize migration. To embody Ubuntu is to see the stranger’s pain as one’s own and to act with fierce compassion.

On the personal level, this means breaking silence, challenging xenophobia, and opening hearts and homes. The prophet Micah demands, “What does the Lord require of you but to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God?” (Micah 6:8). This holy triad must guide every response to migration’s sacred cry.

The story of the displaced is not only a narrative of loss but also a testament to human resilience and divine promise. Let us answer this call with voices raised and hands extended—so that no one walks alone, and every migrant finds a home.

Bibliography

International Organizations and Reports

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Trends Report 2024. Geneva: UNHCR, 2024.

https://www.unhcr.org/statistics

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Various Reports on Humanitarian Crises in Africa. Geneva: OCHA, 2022–2024.

https://www.unocha.org

International Organization for Migration (IOM). World Migration Report 2022. Geneva: IOM, 2022.

https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2023: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Geneva: IPCC, 2023.

https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

African Climate Policy Center. African Climate Change and Migration. Addis Ababa: ACPC, 2023.

https://www.uneca.org/acpc

Biblical and Theological Sources

The Holy Bible, New International Version (NIV). Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011.

Mbiti, John S. African Religions and Philosophy. New York: Doubleday, 1969.

Tutu, Desmond. No Future Without Forgiveness. New York: Doubleday, 1999.

“The Bible and Migration: A Theological Reflection.” Journal of Refugee Studies 31, no. 4 (2018): 517–534.

African Proverbs and Cultural Wisdom

Plaatje, Solomon T. African Proverbs. Johannesburg: Lovedale Press, 1933.

de Ley, Gerd. The Book of African Proverbs. London: University of London Press, 1965.

Oral Collections from Somali, Igbo, Yoruba, Akan, Luo, Shona, Wolof, Swahili, and Congolese traditions (various dates).

Academic and Human Rights Sources

Human Rights Watch. “Darfur: War and Displacement.” HRW Report, 2023.

https://www.hrw.org/africa/sudan/darfur

Amnesty International. “Tigray Conflict: Humanitarian Crisis and Displacement.” Amnesty Report, 2024.

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2024/02/tigray-crisis

Médecins Sans Frontières. “Living in Limbo: Refugee Camps in East Africa.” MSF Field Report, 2023.

“Refugee Experiences in Bidi Bidi and Kakuma Camps.” African Journal of Migration Studies 12, no. 2 (2023): 89–110.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Environmental Impacts of Conflict and Displacement in Africa. Nairobi: UNEP, 2023.