By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

“Omwami asinga obugumu tebaagala kutaasa, naye okutwala ekitangaala ku bantu be.”

(A king who has great strength does not desire to oppress, but to carry the light for his people.) — Luganda Proverb

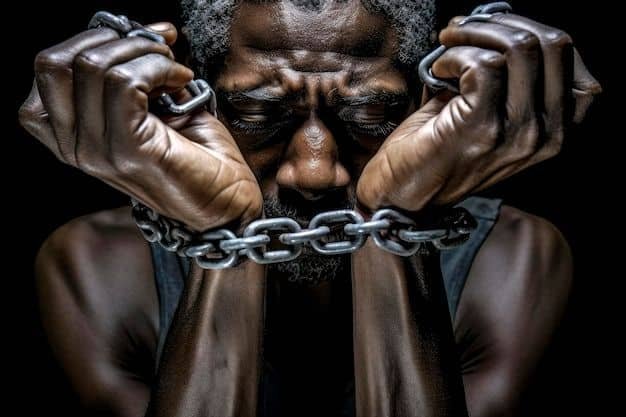

Africa stands not merely as a landmass but as a narrative continent, embroidered with paradoxes, torn between the thronus (throne) of promise and the vincula (chains) of betrayal. Its soil is soaked with centuries of coronations and coups, liberation hymns and lamentations. At the center of this paradox lies the crisis of leadership—a theme not confined to constitutions or elections, but flowing deep into the etymology of rulership itself. In Latin, the rex is not merely a king but one who embodies rectus—rightness, alignment with divine and communal justice. Yet today’s African reges often embody imperium sine iustitia—power divorced from justice, authority corrupted by self-interest.

To lead, ducere, is to draw others forward—not drag them down into servitude. Leadership, when reduced to the spectacle of domination rather than the substance of service, becomes a cruel parody of its etymological soul. The imperium entrusted to Africa’s postcolonial elite was meant to restore dignity and rewrite the story of the captivus—the captive subjected to centuries of imperial rape. Yet the irony is bitter: after overthrowing foreign oppressors, many African nations installed homegrown tyrants. Servitus—once imposed by imperial outsiders—is now replicated in-house, enforced by regimes who wear the garments of democracy but walk in the boots of dictatorship. This is the essence of servitus voluntaria, voluntary bondage: when a people exchange the shackles of colonialism for the golden chains of national betrayal.

Consider the numbers. The 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) by Transparency International paints a sobering fresco: sub-Saharan Africa averages just 33 out of 100, the world’s lowest regional score. Countries like South Sudan (8), Somalia (9), Eritrea and Equatorial Guinea (13 each) mark the nadir of public trust, where leadership is reduced to lootocracy. Only a handful rise above the mire: Seychelles (72), Cabo Verde (62), Botswana and Rwanda (57 each)—not perfect, but flickers of virtus in a continent thirsty for justice. Uganda, emblematic of postcolonial ambition gone awry, registers a mere 26/100, ranking 140th globally. Once a cradle of anti-colonial fervor, its contemporary leadership is caught in the murky waters of militarization and corruption.

The Mo Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) offers a deeper diagnosis. From 2014 to 2023, nearly 78% of Africans experienced a decline in security and democratic freedoms. Even where GDPs rose and health sectors stabilized, the res publica—the public thing—was hollowed out. Democratic rituals continue, but res publica sine populo—a public sphere without the people—is the prevailing malaise. Citizens vote, but their voices are muted beneath the roar of elite ambition.

What fuels this disillusionment? The Afrobarometer 2023 surveys across 39 countries reveal a grievous truth: while 66% of Africans still prefer democracy, only 38% are satisfied with its practice in their nations. Support for military rule—once anathema—has quietly gained ground, with 53% of Africans saying they would accept a coup if their leaders abuse power. In South Africa, the birthplace of Africa’s most celebrated democratic miracle, satisfaction with democracy plummeted by 29 percentage points in a single decade. In Mali, the fall was 23 points. Democracy, it seems, has become aspiratio sine executio—hope without fulfillment.

This erosion of democratic faith is not just institutional—it is psychological, spiritual, and epistemological. The Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o warns that the true colonizer never left. He remains embedded in African minds, shaping leadership through the prism of external validation, not indigenous integrity. To govern from the lens of the oppressor is to adopt the tools of hierarchy while discarding the soul of ubuntu, obuntu, or obwakabaka—systems of collective governance rooted in dignity and reciprocity. The real crisis, then, is one of episteme—a war of knowing. We have leaders without visionaries, kings without prophets, administrators without ancestors.

Let us draw upon Scripture, that ancient wellspring of covenantal governance. Psalm 72, likely written in the shadow of Solomon’s majestic reign, offers a blueprint: the king defends the poor, crushes the oppressor, and flourishes justice like rain on a field. Micah 6:8 compresses the essence of divine leadership into three words: iustitia, misericordia, humilitas—justice, mercy, humility. Luke 22:26 delivers the Christic reversal: “Let the greatest among you be like the youngest, and the leader like one who serves.” This inversion is the soul of true regnum: not domination, but ministrare—to serve. In Latin logic, the true magister is the one who first becomes minister.

History gives us glimpses of this ethos in action. Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso renamed his nation from “Upper Volta” to “Land of Upright Men,” rejecting imperial legacies. He abolished ministerial privileges, rode bicycles instead of limousines, and declared: “He who feeds you controls you.” His leadership was a brief eruption of virtus in a region choked by venalitas—venality. Nelson Mandela, too, understood clementia and moderatio, stepping down after one term in power and refusing to let his name become a crown. Yet these are exceptions, not the rule. For every Mandela, a Mobutu; for every Sankara, a Bashir.

Still, the winds may shift. Rwanda’s Office of the Ombudsman, established in 2003, has clawed back over $12 million in misappropriated public funds and now enjoys constitutional independence. Côte d’Ivoire, once ravaged by civil war, has made strides in electoral reform. Benin’s Court of Audit, bolstered by civil society watchdogs, has pushed transparency forward. The success is uneven, yet undeniable.

And what of the youth, the iuventus who now make up over 60% of Africa’s population? Their passion pulses on Twitter, in spoken-word, in voter drives, in the resistance of Sudanese streets and Congolese classrooms. If leadership is to be reborn, it must arise from these wellsprings—not from foreign blueprints but from inner awakening. As philosopher Kwame Nkrumah thundered: “Seek ye first the political kingdom, and all things shall be added unto you.” But today, Africa must seek first the ethical kingdom—or risk having all things taken away.

The solution is not to import Western models wholesale. It is to incarnate ancient virtues in modern governance. It is to re-narrate Africa’s story: one where the rex is a servant, the imperium is a calling, and the virtus is not theatrical charisma, but moral courage. It means shifting from praedatio (predation) to praeparatio (preparation), from captivus to liberator, from thronus sine lumen to thronus cum lux—a throne that bears light.

Indeed, the chains can be broken. But it will take a generation of leaders who do not mistake authority for entitlement, or legacy for license. It will require a theology of governance, a psychology of liberation, an economics of justice. It will demand that we teach children not only history, but historia sacra—the sacred stories that remind us who we are.

And so we return to the Luganda proverb: “A king who has great strength does not desire to oppress, but to carry the light for his people.” Africa does not lack kings. It lacks light-bearers. The throne stands. The chains, though many, can be broken. The question is not whether we can lead—but whether we will lead in the light of virtue, or in the shadow of vanity.

Let Part One end not in despair, but in decision. The thronus awaits. Will it be occupied by kings or captives ?