By Emmanuel Mihiingo Kaija

“The oppressor must never be allowed to shape the imagination of the free.” — Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

“Non ducor, duco.” — I am not led; I lead. — Civic motto of São Paulo

“Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind.” —

Romans 12:2

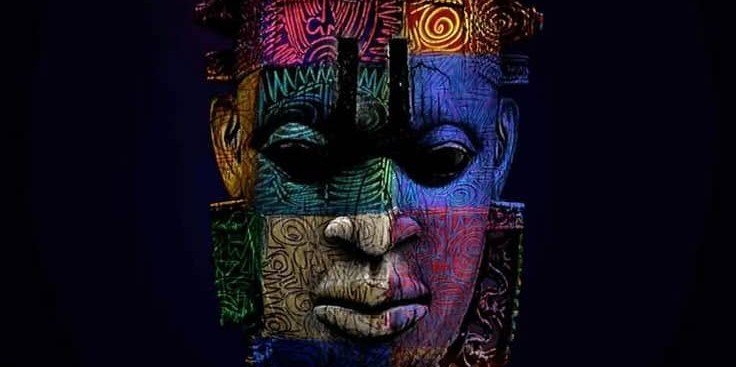

In the quiet chambers of the African soul- let me imagine- power transcends politics, unfolding as a spiritual and psychological drama across centuries. The masks that African leaders wear are forged, not in vanity, but in the crucible of colonial trauma, rupture, and the deep human longing for dignity. Like Cain—cursed, wandering east of Eden, yet marked by God (Genesis 4)—the African leadership psyche bears fear and pride. And yet Scripture assures that even Cain’s exile was under God’s protective mark. Contrast that with David, raised from shepherd boy to king (1 Samuel 16), whose reign was defined by repentance, worship, and dependence on divine wisdom. That mirror—God’s Word—calls leaders to “search me, O God, and know my heart” (Psalm 139:23) as David did, wrestling with the shadow within. Carl Jung’s concept of the unconscious shadow resonates here: until one faces one’s suppressed fear or shame, one remains captive to repetition. And as Paul exhorts in Romans 12:2, transformation begins with the renewing of the mind—not mere external conformity. The mask is both defense and distortion; the mirror is divine illumination revealing wound and calling to wholeness.

Psychological captivity is more enduring than chains or colonial rule. Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks describes how colonized minds internalize inferiority and mimic the colonizer’s image—even seeking approval through accent, attire, or titles. For Fanon, the colonized self becomes divided, wearing “white masks” to approach the world of the oppressor . As Ngũgĩ waged in Decolonising the Mind, the first target of conquest was the language—“If you know all the languages of the world but not your mother tongue, that is enslavement” . He further declared, “To speak one’s language is to celebrate one’s identity, but to impose a language is to practice tribalism of another kind” . Unless leaders face these internal demons—pride, fear, insecurity—power remains a poison, intoxicating and destructive. Biblical repentance and kenosis of Christ (Philippians 2:5–8) invite those who lead to become servants—shepherd-kings renewed in humility.

The biblical imagery of Babel (Genesis 11) and Babylon (e.g. Daniel, Revelation) conveys the fragmentation of culture, tongues, and spirit. Africa’s postcolonial condition echoes Babel’s linguistic alienation and Babylon’s exile. Yet Pentecost (Acts 2) offers hope: unity amid diversity by the Spirit, restoring communication across broken tongues. African leadership must emulate Pentecost—reclaiming indigenous languages and ancestral wisdom not as nostalgia, but as instruments of revelation and reconciliation.

Wisdom remains the bedrock of authentic leadership. Solomon’s prayer (1 Kings 3:9–12) sought the capacity to judge rightly and rule equitably. Christian theology aligns this hokhmah with biblical virtues—and African philosophies like ubuntu and harambee affirm leadership as relational and sacrificial. Aristotle’s phronesis (practical wisdom) and Mbiti’s communal knowledge converge here. These ideals oppose colonial potestas—raw domination—and reclaim auctoritas, moral authority rooted in justice, mercy, and covenantal responsibility.

Language and culture are the incarnational heart of leadership. Just as the Logos (John 1) became flesh—choosing to dwell in culture and language—African leadership must embody identity in mother tongues and local customs. Ngũgĩ himself wrote masterpieces in Gĩkũyũ, arguing that mother-tongue expression is pivotal to self-affirmation and decolonization. “If you know all the languages of the world but don’t know your mother tongue, that is mental colonization” . Another wrote:

“If you know all the languages of the world… and you don’t know your mother tongue … that is self enslavement.”

Such alienation not only disrupts identity but undermines meaningful leadership, separating leaders and led by linguistic and cultural distance.

Data further illustrate this disconnect. A supra-national Afrobarometer survey of 34 African countries (51,600+ citizens) found about 75% of people support limiting presidential mandates to two terms, yet third-term bids persist, revealing deep rupture between citizens and their leaders . Meanwhile, multiple presidents like Paul Biya, in power since 1982, still seek extensions—illustrating the persistence of authoritarian mimicry in postcolonial governance.

Finally, the New Covenant, prophesied in Jeremiah 31:31–34—where God writes the law on inward hearts—signifies leadership grounded in transformation from within. Christ, the Servant-King, did not grasp power but emptied Himself (Philippians 2:5–8), modeling leadership rooted in love, humility, and service. The apostolic vision (1 Timothy 3; Titus 1) demands overseers of integrity, gentleness, and sacrifice—qualities sorely needed in contexts where power often breeds exclusion and corruption.

Conclusion: From Mask to Mirror

The pilgrimage from mask to mirror is spiritual and psychological. It is a journey of repentance, renewal, and reimagination. It challenges leaders to dismantle internalized oppression, reclaim their identity as God’s image-bearers, and adopt leadership as sacred custodianship rather than dominion. When masks fall and mirrors shine, African leadership radiates with justice, mercy, humility, and love. The throne is no longer captive—it reflects the glory of the Creator through the servant-king’s humility, revealing a leadership forged in shalom and transformation.

Emkaijawrites@gmail.com