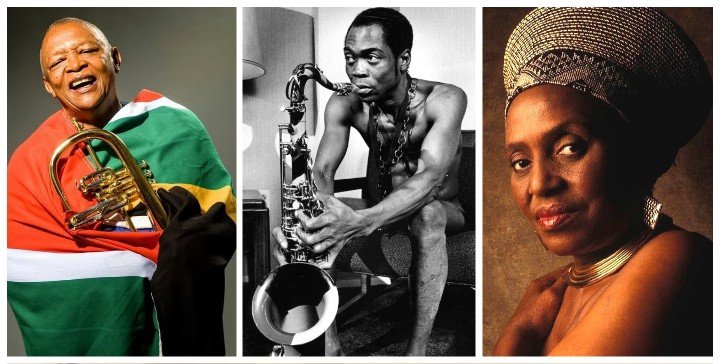

From left to right: Hugh Masekela, Fela Kuti and Miriam Makeba

Source: Africa Publicity

In the fight for freedom and independence across Africa, music emerged as a powerful tool for resistance, unity, and expression. Through song, African communities communicated their struggles, hopes, and determination to break free from colonial rule and oppressive regimes. In countries like South Africa, Nigeria, and Congo, music became a rallying cry for revolution, unifying people across different regions, languages, and social backgrounds. This story explores the critical role music played in these liberation movements, focusing on specific case studies from these three nations.

South Africa: The Anthem of Resistance

South Africa’s fight against apartheid is one of the most well-documented liberation struggles in modern history. During this period, music became an essential part of the anti-apartheid movement, inspiring generations of South Africans to continue their fight against an oppressive system. Music was more than entertainment; it was a form of protest, a way to empower communities, and a medium through which messages of defiance could reach the masses.

One of the most iconic anthems during this period was “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika,” originally composed by Enoch Sontonga in 1897. The song’s beautiful melody and evocative lyrics soon became a symbol of resistance, sung at political rallies, funerals of fallen activists, and gatherings of freedom fighters. Over time, it transformed into an anthem that transcended racial and ethnic lines, representing the collective struggle for equality.

Sibongile, a young activist from Soweto, recalls how singing this song in the streets filled her with strength. “We knew the government was listening, but through music, we could tell our stories without fear,” she says. “Music gave us hope when we had nothing else.”

Artists such as Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba also used their global fame to bring attention to the struggles of South Africans. Masekela’s song “Bring Him Back Home,” written for Nelson Mandela while he was imprisoned, became a beacon of hope. The song demanded the return of Mandela to lead the people to freedom, resonating with many who sought a political leader to end apartheid.

Makeba, often referred to as “Mama Africa,” used her platform to criticize the apartheid government while in exile. Songs like “Soweto Blues,” a collaboration with her then-husband, Hugh Masekela, reflected the brutality faced by protesters, particularly during the Soweto Uprising. Her voice became a weapon, and through her song, the world was reminded of the atrocities in South Africa.

For South Africans, music was not just a cultural expression; it was a lifeline, a way to keep the spirit of resistance alive in the darkest times. As apartheid fell, many of these songs, once banned by the regime, became symbols of victory and remembrance, forever marking the role music played in the nation’s liberation.

Nigeria: Rhythms of Independence

Nigeria’s path to independence in 1960 was shaped by a vibrant cultural landscape, and music played a key role in unifying the people. Fela Kuti, the legendary Afrobeat pioneer, became one of the most outspoken musicians during Nigeria’s post-colonial era, critiquing the government and using his music as a form of activism. His sharp lyrics, infused with traditional African rhythms and jazz, resonated deeply with Nigerians, especially in the fight against military dictatorship in the 1970s.

Fela’s music, particularly songs like “Zombie” and “Coffin for Head of State,” took aim at the government and the military. “Zombie,” for instance, was a direct attack on the Nigerian army, calling out its soldiers for blindly following orders, a metaphor for the government’s oppressive tactics. His music was filled with satire and anger, and while his songs were catchy, they also carried a heavy political message that ignited a fire within his audience.

However, it wasn’t just Fela Kuti who used music to shape Nigeria’s liberation movements. Even before his rise to fame, traditional Nigerian music played an important role in the country’s fight for independence. In northern Nigeria, the praise songs of Hausa griots celebrated the heroes of anti-colonial movements, passing down stories of resistance from one generation to the next.

In the eastern region, Igbo highlife music, with artists such as Osita Osadebe, inspired communities to come together, celebrating their cultural identity while calling for a united Nigeria. Osadebe’s songs weren’t as explicitly political as Fela’s, but they reinforced the spirit of Nigerian independence by promoting unity and pride in one’s heritage.

One such song, “Osondi Owendi,” became a symbol of resilience among the Igbo people. Kelechi, a young man from Enugu, remembers how his father used to hum the tune as they listened to the radio. “It wasn’t just a song to us,” he says. “It represented the joy of independence and the hope of building a new Nigeria.”

Music, in all its forms, became a reflection of Nigeria’s complex political landscape, with artists both uplifting their communities and holding those in power accountable.

Congo: Songs of Unity and Revolution

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) has a long history of political turbulence, from the days of colonization to the post-independence dictatorships. Music, especially rumba and soukous, played a crucial role in unifying the people during these turbulent times.

In the early 1960s, when Congo gained its independence from Belgium, artists like Joseph Kabasele, known as “Le Grand Kallé,” created music that celebrated the newfound freedom. His song “Indépendance Cha-Cha” became an anthem for independence not just in Congo but across many African countries. Sung in Lingala, the song reflected the excitement of liberation and the hope for a brighter future.

During the rule of Mobutu Sese Seko, however, music took on a more defiant tone. Artists like Franco Luambo and Tabu Ley Rochereau continued to create soukous music that entertained the masses while subtly critiquing the government’s corruption and human rights abuses. Franco’s songs, often laced with hidden meanings, became a way for Congolese people to express their frustrations.

In Kisangani, a young activist named Mbuyi recalls how he and his friends would gather in secret to listen to Franco’s music. “We couldn’t say what we felt openly, but through Franco’s songs, we found a voice,” he explains. “Music became our way of speaking truth to power.”

As the country descended into civil war in the late 1990s, music once again became a form of resistance and survival. Songs from artists like Werrason and Koffi Olomide carried messages of peace and reconciliation, trying to bridge the ethnic and political divides tearing the country apart.

Conclusion: The Power of Music in African Liberation

In each of these countries—South Africa, Nigeria, and Congo—music played an instrumental role in their liberation movements. From the anti-apartheid anthems in South Africa to the Afrobeat protest songs of Nigeria, and the unifying rhythms of Congo’s rumba, music has always been more than just sound. It has been a voice for the voiceless, a rallying cry for justice, and a beacon of hope for oppressed people. Through music, Africans were able to express their desires for freedom, challenge oppressive systems, and ultimately, reshape the political landscape of their nations.

Music’s impact on African liberation movements is a testament to its power as a universal language—one that can cross borders, defy regimes, and inspire generations to fight for their rights.