By: Isaac Christopher Lubogo

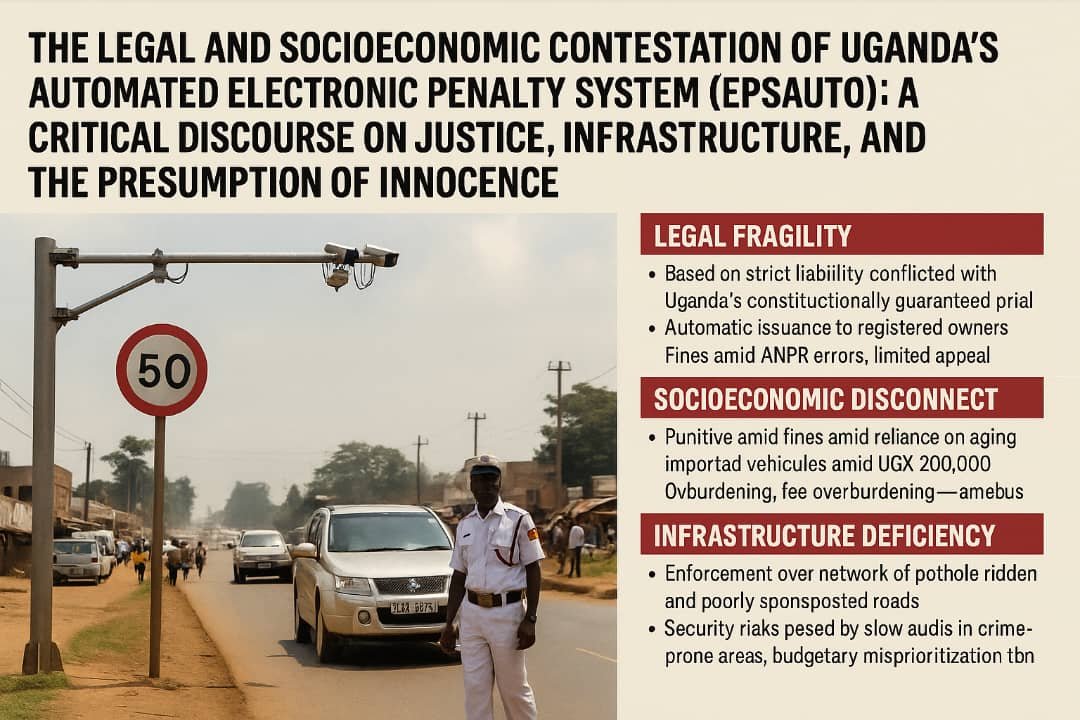

The introduction of Uganda’s Automated Electronic Penalty System (EPSAuto) under the Intelligent Transport Monitoring System (ITMS) in April 2025 has ignited a wave of public outrage, legal scrutiny, and constitutional contestation. Enacted through a Ministerial directive from the Uganda Police Force in collaboration with a private contractor (allegedly of Russian origin), the system automates the process of traffic law enforcement using Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) and red-light cameras. Infractions such as overspeeding and signal violations are captured, verified, and electronically ticketed to the registered vehicle owner’s phone number or email, who must pay a fine—UGX 200,000 for 1–30 km/h overspeed and UGX 600,000 for higher speeds—within a 28-day (or in some instances 72-hour) window or face a 50% surcharge and administrative sanctions, including impoundment, denial of license renewal, and suspension of travel privileges.

At first glance, EPSAuto represents an infrastructural leap towards digital governance in traffic enforcement, offering a technocratic alternative to the notoriously corrupt and manually enforced Express Penalty Scheme (EPS). Yet beneath its glossy promise of automation and order lies a storm of constitutional, economic, infrastructural, and moral contradictions that threaten not only the credibility of the system but also the legitimacy of the state’s coercive power.

1. Legal Fragility: The Burden of Guilt Without a Trial

At the heart of the legal storm is the system’s foundation on strict liability—a principle where the registered owner of the vehicle is deemed guilty the moment a traffic camera captures a violation, regardless of whether they were the driver. This raises profound questions under Article 28(3)(a) of the Constitution of Uganda, which guarantees every person the right to a fair hearing and the presumption of innocence. The logic of EPSAuto presumes guilt and exacts punishment prior to any court process or opportunity for meaningful challenge, thereby reducing constitutional protections to ceremonial rhetoric. The fact that fines escalate automatically without judicial oversight further exacerbates this erosion of procedural justice.

Furthermore, the system’s overreliance on electronic evidence—screenshots or short video clips—is not immune to error or tampering. Misreads by ANPR technology, poor lighting, or multiple vehicles in frame can implicate innocent motorists, particularly in a country with unreliable internet access, frequent power failures, and manual data entry errors that accompany such transitions. The appeal process, while theoretically available, is burdensome, opaque, and poorly communicated, giving citizens minimal hope of recourse.

2. Socioeconomic Disconnect: Justice Without Context is Injustice

EPSAuto was deployed into a socioeconomic ecosystem utterly unprepared for its rigidity. Uganda is a country where the majority of vehicle owners depend on imported second-hand vehicles, often in poor mechanical condition, with faulty speedometers and braking systems. The public transport sector—particularly taxi and boda boda drivers—operates on razor-thin profit margins. To charge a low-income commuter UGX 600,000 for slightly exceeding a poorly signposted speed limit is not deterrence; it is extortion masquerading as governance.

For context, the minimum monthly wage in Uganda is UGX 130,000. One speeding violation of 1–30 km/h over the limit carries a UGX 200,000 fine—more than a month’s salary. If the payment is not made within the extremely tight 28-day or 72-hour window, a 50% surcharge is added. This is akin to sentencing a peasant to a financial gallows for stepping out of a queue. Worse still, in many cases, multiple fines are incurred in a single day, with no forewarning. A recent example saw a driver slapped with three penalties totalling UGX 1.4 million—escalating to UGX 2.1 million after surcharges—due to repeated detection by different cameras along a stretch with no signage.

This is not enforcement. It is financial ambush.

3. Infrastructure Deficiency: Criminalizing the Consequences of State Neglect

The enforcement of EPSAuto is happening in the context of structurally failed road networks. Speed limits are often inconsistently placed or entirely missing. Streetlights are dysfunctional. Road markings have faded into obscurity. Potholes, road shoulder erosion, and illegal humps force erratic driving patterns. In this scenario, to criminalize a motorist for failing to comply with a speed sign that doesn’t exist, or to fine someone for lane-switching to avoid a pothole, is not merely unjust—it is state-sanctioned sabotage.

Even more troubling is the application of 30 km/h limits on highways and bypasses where such speeds are impractical, leading to new dangers. Slowing down in crime-prone areas in the name of speed compliance makes drivers sitting ducks for armed robbers. The law has become a death trap, and the state is the architect of the hazard.

4. The Corruption Bypass Fallacy: Automation Without Reform

One of the primary arguments in favour of EPSAuto is that it eliminates the need for interactions with traffic police, reducing opportunities for bribery and extortion. While this is a valid objective, the reality is that EPSAuto is not replacing the corrupt system—it is bypassing it without cleansing it. Traffic officers continue to issue manual tickets for violations outside EPSAuto’s jurisdiction (e.g., lack of seatbelt, insurance), and some have been implicated in selectively disabling cameras, colluding with private contractors, or manipulating the fine databases.

The government has refused to disclose the private-public profit-sharing agreement. Reports suggest that the majority of collected fines are channelled to a foreign contractor, leaving only 15% with the Uganda Police, and virtually nothing trickles down to road improvement or driver education. This cloaked financial arrangement fosters distrust, casting doubt on whether safety is the real objective.

5. Global Best Practices Ignored: What Uganda Ought to Have Done

Globally, automated traffic enforcement is deployed only after satisfying a suite of preconditions: comprehensive stakeholder consultation, phased geographic implementation, public education campaigns, installation of clear and consistent signage, graduated penalties tied to income levels, and robust appeal mechanisms. In Turkey, for instance, the TEDES system only allows one fine within a 5-minute window to avoid stacking of multiple infractions along one stretch. In the UK, the appeals process is independent, fines are income-graded, and any revenue is legally mandated to fund road improvements. Washington D.C. publishes annual audits and safety impact reports to assess proportionality and performance.

Uganda did none of the above.

There was no public consultation. There was no test run. There was no transparency in contract awarding. No sensitization of road users. No infrastructural rehabilitation. No judicial oversight mechanism. EPSAuto is a technocratic shock therapy to a traffic system riddled with wounds that the state itself inflicted through decades of neglect.

Conclusion: From Punitive State to Protective State

The EPSAuto system, as it currently operates, embodies a paradox: it claims to uphold law and order while simultaneously undermining the very spirit of justice and constitutionalism. It claims to be pro-life yet traps poor citizens in cycles of financial death. It promises fairness yet privileges the contractor over the commuter. It assumes guilt before the courts have spoken. And worst of all, it enforces compliance with laws the state has made impossible to obey—through underinvestment, corruption, and disregard for public input.

To redeem this project from its authoritarian and exploitative posture, Uganda must pause EPSAuto immediately, subject it to parliamentary review, launch a national public hearing, renegotiate the private partnership for transparency and equity, revise the law to protect presumption of innocence and due process, and allocate part of the collected fines to road improvement and public sensitization. Without such reforms, EPSAuto will remain an efficient tool for injustice—a mechanical monster guised in legal uniformity, but breathing the fire of socioeconomic oppression.

This is not the traffic revolution Uganda needs. It is the chaos of digitized punishment dressed as progress.

About the Author:

Isaac Christopher Lubogo is a Ugandan lawyer and